Classic Cookbooks: The Settlement Cook Book, The Way To A Man's Heart

When my grandmother died almost 11 years ago and the family divided up her possessions, I ended up with some jewelry, her mink jacket, a gold-plated cigarette lighter from the Sands Hotel in Las Vegas (non-functioning, alas), a rocking chair that neither my mother nor aunt wanted but also didn't want to throw away, and a pair of cookbooks: Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Volume One by Julia Child, Simone Beck, and Louisette Bertholle and The Settlement Cook Book by Mrs. Simon Kander.

My grandmother was not a domestic goddess by any means. Her mother had had a difficult childhood: her father had died when she was still very young and, as the oldest girl in the family (there were seven kids in all), she'd been responsible for a lot of housework and childcare. When she and my great-grandfather married, he promised her she would never have to be a household slave again, which is maybe the most romantic thing that has ever happened to anyone in my family.

And so when Grandma was growing up, there was always "help" and she never had to cook or clean or do dishes. She and her sister went to college and got their degrees, just like their brother did. She met my grandfather just before the start of World War II and they got married the day after she turned 21, which was the day after she graduated from college. Almost as soon as he came back from the South Pacific, she got pregnant with my aunt. My mother came along four years later. It was the '50s. A lot of women who were married and had children still worked in the '50s, but not middle-class ladies whose husbands earned enough to support the whole family. That is, women like my grandmother.

Except that Grandma hated being a housewife. After my aunt and mother were old enough to go to school, she had nothing to do all day besides housework. She found it depressing. So she put her degree to use and got a job teaching second grade at the neighborhood school, where she stayed until she retired 20 years later. Her salary paid for the services of a woman named Louie who came in three days a week to clean the house and cook dinner. I've always admired her for this, for finding a way to escape a job she hated and do the one that she was trained to do and that actually interested her.

Many years later, when I was grown up and in grad school, I called her up to chat and told her about a new professor who everyone in our department was in love with because he was younger and handsomer than the rest of the professors. "Is he Jewish?" she asked me. He was. "Bake him a cheesecake!" she told me. "The way to a man's heart is through his stomach!" (Cheesecake happened to be one of Grandma's four signature recipes that she passed down to us all. She got it from a Dear Abby column. The others were a chocolate chip bundt cake, a chocolate meringue pie, and a beef barley concoction she called Junk Soup.)

"So that's how you bagged Grandpa," I said. I was trying very hard not to laugh.

"No, no," she said. "Everything I made him tasted like wax." And then even after I really did start laughing because it was so retrograde and because she had never said anything like that to me before, she insisted: "Bake him a cheesecake! The way to a man's heart is through his stomach!"

Every time I thought of that conversation, I laughed again. It became the basis for a lot of jokes involving the professor. I considered baking Grandma's cheesecake for the department holiday potluck, but I went with her chocolate meringue pie instead. It did not pave a way through the professor's stomach to his heart, which I suppose was probably just as well since he was on my thesis committee.

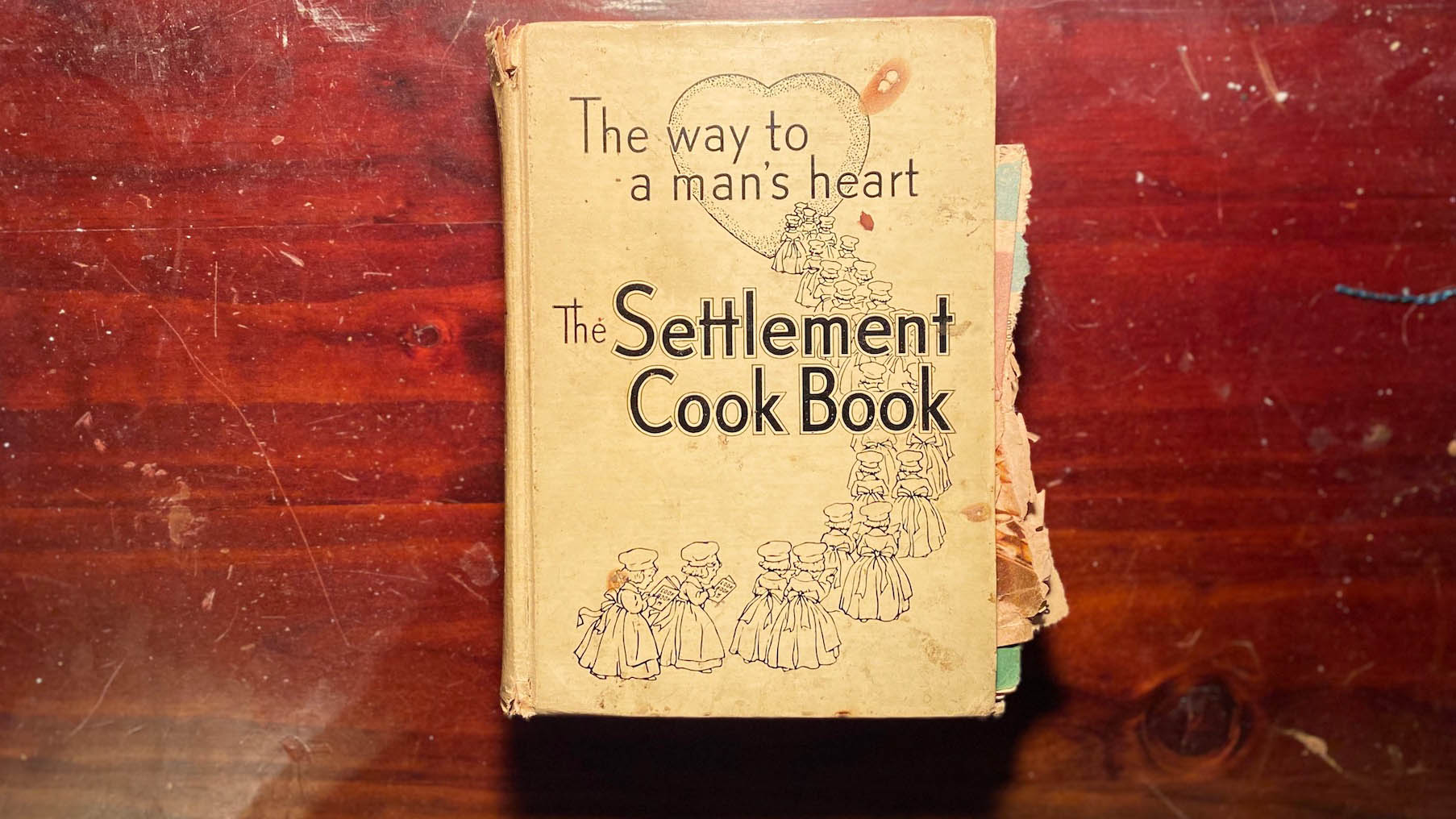

I thought of it again after the funeral when we were going through her things and I came across her copy of The Settlement Cook Book, which declared, on both the cover and the spine, "The way to a man's heart." (On the cover, this was illustrated by a crowd of women in aprons and chef toques parading two by two toward a giant heart.) Presumably these were the recipes that had won the heart of Mr. Simon Kander. I picked it up and brought it home with me.

And then it sat on my shelf for ten years. Unlike her copy of Julia Child, which was pristine, Grandma's Settlement Cook Book had a worn cover, a broken binding, and was stuffed with newspaper clippings of recipes, mostly desserts.

"See? You come by your sweet tooth naturally," my mother said when I called her up to ask if she remembered Grandma making anything from The Settlement Cook Book. "Is there a recipe for veal in tomato sauce in there? I liked when she made that." There was not.

I flipped through looking for stains on the pages that indicated how the book had been used. The cakes and cookies chapters looked fairly well-thumbed. There were markers at the recipes for dumplings and for spaghetti, and the book naturally fell open at the sections on coffee and ice cream. But there was nothing that told me anything new or interesting about her, like which particular recipes she was really into—each page had five or six—or if she ever went through phases, like my recent period of eating pancakes for dinner three times a week. Or maybe she was just a more tidy cook than I am.

I was a little disappointed, but not surprised. Why would a woman who had help cooking dinner three times a week spend enough time poring over a cookbook to leave a permanent mark?

The Settlement Cook Book, as I learned when I started looking into it, was not just any cookbook. It lives at the intersection of Fannie Farmer's Boston Cooking-School Cookbook and The Joy of Cooking, but with its own very special Midwestern Jewish accent. It's not a kosher cookbook. It doesn't even have very many recipes that would make someone say, "Oh! Jewish food!" But it's very much a reflection of its creator.

Mrs. Simon Kander was not always Mrs. Simon Kander, the stout, handsome white-haired woman whose autographed photo—"Very Truly Yours, Mrs. Simon Kander"—appears on the frontispiece of every edition of The Settlement Cook Book. In the beginning, she was Lizzie Black, the daughter of a well-to-do German-Jewish family in Milwaukee. Lizzie was the valedictorian of her high school class and at graduation gave a speech called "When I Become President." But it was 1878 in Milwaukee, so instead of doing whatever people did to work their way up to the presidency, Lizzie married Mr. Simon Kander. The Kanders had no children, so Mrs. Kander had a lot of time to spend on philanthropy. Anytime wealthy Jews in Milwaukee were doing Good Works, she was there.

In 1898, Mrs. Kander began teaching classes at the Milwaukee Jewish Mission, which merged with another organization two years later to become The Settlement. Mrs. Kander became the president, a role she would hold for the next 18 years. (At last, she was president! Though probably not the presidency she anticipated at her high school graduation.) Like other settlement houses around the country, it was meant to be a place for immigrants to come and learn the ways of Americans. Mrs. Kander was particularly eager to help Eastern European Jewish immigrants, largely because she felt their un-Americanized ways cast a poor light on the descendants of earlier German-Jewish immigrants like herself. She wanted to lift up the whole tribe. Her way of helping was to teach a class to women on how to be economical housewives.

By 1901, it occurred to her that requiring the students to copy down all the recipes wasted valuable class time, so she asked the (all-male) board of the Settlement House for $18 to print recipe pamphlets (the equivalent of around $500 today; 18 also happens to be an important number in Jewish numerology, signifying life). They denied her request. Undaunted, Mrs. Kander solicited ads from local businesses and collected enough money to print 1,000 copies of what became the first edition of The Settlement Cook Book. They went for 50 cents apiece. The first run sold out within a year, and Mrs. Kander set to work on a second edition. The third edition, in 1907, was sold in Chicago, and The Settlement Cook Book went national after that, carried to various corners of the country by Midwestern Jews. Mrs. Kander personally supervised edits and updates to every subsequent edition until her death in 1940; afterwards, others took over, but her name and picture remained. Proceeds from the cookbook, among other things, financed the new Milwaukee Jewish Community Center.

It's interesting to me how women like Mrs. Kander spent their lives creating an elaborate facade of subservience, to the point of going by their husband's names and pretending they had no interests besides hearth and home, when really they were anything but. What would have happened to them if they'd been able to seize power directly? Would they have ended up in the same bind as powerful 21st-century women—Hillary Rodham Clinton comes most readily to mind—who waste so much time dealing with optics and pantsuits instead of doing things? (My grandmother ran a similar subterfuge: for her entire life, she made a great show of seeking and appearing to defer to men's opinions, and then she proceeded to do exactly as she pleased.)

Mrs. Kander wasn't a home economist like Fannie Farmer. She wasn't interested in the scientific principles behind cooking, though she did provide tables of nutritional information, credited to the National Live Stock & Meat Board of Chicago. There are no gentle jokes to put new cooks at ease like "Stand facing the stove," the opening line of Irma Rombauer's Joy Of Cooking. Instead we get, "Cooking is the art of preparing food by the aid of heat, for the nourishment of the human body." Mrs. Kander is all business.

Judging by the introductory chapters of The Settlement Cook Book, where her personality shines through most clearly, Mrs. Kander's idea of economical housewifery was shaped by her own personal experience. Consequently, there's a lot of information about how to set a table for a dinner party (always a tablecloth, and remember, the longer one is for dinner, and you don't need a table pad under lace), how to serve the guests, and what to do if you don't have a servant to help you. (Mrs. Kander recommends one "waitress" for every four to six guests.) In the world of The Settlement Cook Book, everyone has a well-stocked and -equipped kitchen, a separate dining room, and adequate laundry facilities, but there are also instructions on how to build a fire if it's absolutely necessary.

And then, after a chapter about how to feed babies and invalids (and you'd better believe there's absolutely nothing in there about breast-feeding), come the recipes, hundreds of pages of them, including just about anything you would ever want to cook if you were a Jewish lady in Milwaukee at the turn of the 20th century who had fond memories of the German immigrant treats of your childhood but also a great desire to be as American as possible. That was all Mrs. Kander, too. The recipes are brief, almost telegraphic, and in parts unintelligible. Mrs. Kander didn't always bother to include things like oven temperatures or precise cooking times. Perhaps people just knew things back then. For the same reason, the cookbook also doesn't include many recipes from the traditional Jewish repertoire. Mrs. Kander's students already knew how to make matzo balls and kreplach. But shrimp wiggle? That was what Americans ate!

The point of the cookbook, Angela Fritz wrote in a 2004 article in the Wisconsin Magazine Of History, was, despite its tagline, "not to catch a man but to become an 'American.' It was Lizzie Black Kander who set those goals, and in the course of achieving them created a piece of American culture that could be found in kitchens throughout the country."

My grandma's copy of The Settlement Cook Book is the 28th edition, published by the Settlement Book Co. in September 1947, seven years into the post–Mrs. Kander era. (There have been 40 editions in all. The later ones acknowledge the death of Mrs. Kander and are known as The New Settlement Cook Book and published by Simon & Schuster.) At the time, she would have been a young mother in Detroit, managing her own household for the first time in her life. I imagine the book would have been a gift from her mother or one of her aunts. Or maybe from her father, whom she adored, and who would, a few years later, after she had moved to Chicago, give her a stern lecture about the importance of establishing her own life instead of running home to her parents every time things got tough. At least that is the family legend, but now that I think about it, it's not hard to see a link between this and her decision to give up her depressing attempts at homemaking and start teaching school.

The Settlement Cook Book was, for the women of the Milwaukee Settlement, a guidebook to a new life. For Mrs. Kander, it was a way to become the executive she always knew herself to be. For my grandmother, maybe, it was an instruction manual for a life she tried out and decided she didn't want. Maybe all great cookbooks are like that, from The Joy Of Cooking, which was Irma Rombauer's way of rebuilding her life after her husband's suicide, to Mastering The Art Of French Cooking, a chronicle of Julia Child's own mastery of the art. The wonderful thing about them is that they show us how to change our lives with every meal.