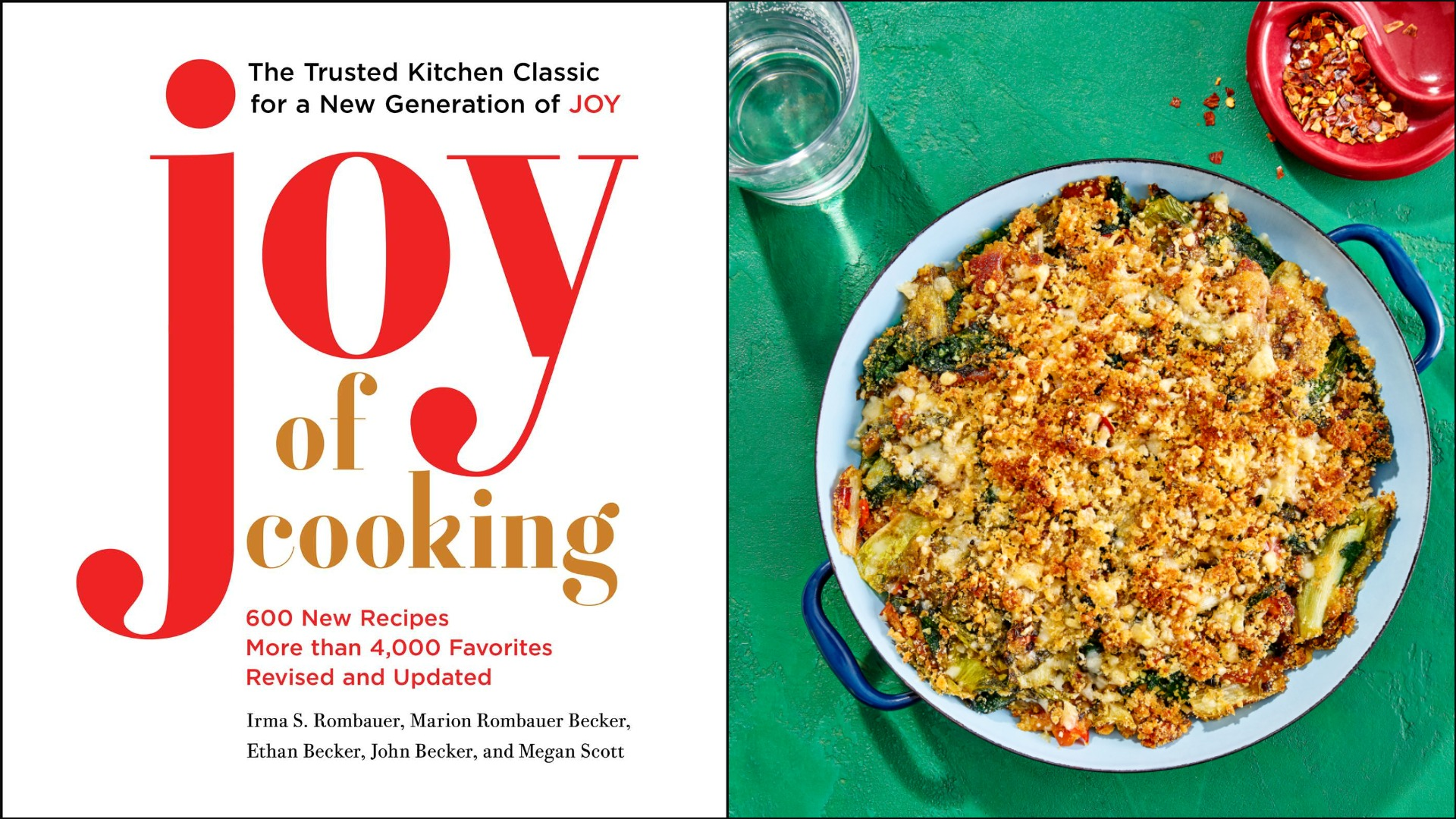

The New Joy Of Cooking keeps It In The Family

It's not entirely fair to say that Joy of Cooking is responsible for John Becker and Megan Scott's entire relationship. But it's also not entirely fair to say that it's not.

It is fair to say that Joy has been the center of their lives for nearly as long as they've known each other.

The two met about a decade ago in Asheville, North Carolina. Megan was working in a bakery and John was working in a coffeehouse down the street. They'd become friendly, as people who work service industry jobs in the same area do.

"I'd been reading a book for a class about women and religion," Megan tells me, recalling their meeting. "I told him about it, and he managed to say something kind of intelligent."

"If there was anything I learned in college," John says, "it was how to talk about things I knew nothing about and sound intelligent."

One day Megan happened to be talking to a coworker about how much she loved Joy of Cooking. She'd bought a copy when she first moved out on her own and had learned it to teach herself how to cook. The coworker said, "Did you know that the guy whose family wrote that book works at the coffeehouse down the street?"

The next time Megan went to the coffeehouse, John was behind the counter, and she asked him if he was connected to Joy. He blushed and admitted, "That's my family."

More specifically, it was his great-grandmother Irma Rombauer, grandmother Marion Becker, and father Ethan Becker. But John had always been encouraged to follow his own path. In college, he had studied literature and had worked as an editor, but a life in academia didn't especially appeal to him. He was, however, starting to become a fairly competent home cook.

That day in the coffeeshop, Megan asked him what he did when he wasn't working. He didn't pick up on the cue at first and told her about his Cormac McCarthy book club. Eventually, though, he caught on.

Now they are married and together have spent the past nine years writing the ninth and most recent edition of Joy, out next month.

The legend of Joy began in 1930 in St. Louis. The stock market had just crashed and Irma Rombauer's husband, Edgar, had just committed suicide. Irma needed some way to make a living and decided to write a cookbook. Until then, as her daughter Marion later recalled, she'd been more interested in the conversation around the table than what was on it. But, as John and Megan note in the new edition, this proved to be an advantage: She was writing for other people who were less-than-expert in the kitchen and wanted to learn to put meals together. The first directive in the self-published 1931 edition was, endearingly, "Stand facing the stove." Marion designed the cover and helped sell it in St. Louis and across the Midwest. A commercial publisher picked it up, and within a few years, it became an American classic, beloved by everyone, from recent college graduates to Julia Child.

As the years passed and the book went through more editions, it grew and grew and grew to its current doorstop size. You can learn to do just about anything in the kitchen from Joy, from boiling an egg to deboning a chicken without breaking the skin. It lacks beautiful photography or engaging anecdotes, but its range is unparalleled. A few years back, I was writing an article about prairie chickens and was stumped about how to prepare them; one afternoon, flipping desolately through my own copy of Joy (2006 edition), lo and behold, there were detailed instructions about how to dress and cook a prairie chicken.

That was likely the influence of Ethan Becker, Marion's son, an outdoorsman whose true vocation is designing knives, but who was recruited into the family business in 1976. And in 2010, exhausted after years of disputes with the publisher at the time, Macmillan, he handed it over to John and Megan.

By then, John had decided to embrace his family tradition. Megan was already interested in food; before she worked at the bakery, she'd worked as a cheesemaker at a goat dairy. John realized he liked researching and nitpicking, and Joy was essentially one enormous research project. "I was like, 'Holy crap, I have this thing!'" he says. "It's an amazing thing to inherit," Megan agrees.

Their first task was working on an app version of the book (it's no longer for sale). In the process, they got to know the book really well. They began to trace the lineage of the recipes back to the edition in which they'd first appeared. They sifted through filing cabinets filled with notes from recipe testers from the 2006 edition, plus a file card system that Marion had developed back in the 1970s. When they finally began testing recipes, they were able to figure out where mistakes had come in and how to fix them.

For example, pancakes. Megan noticed that the batter was thinner than she thought it should be. Going back through the paper trail, she and John found that in either the 1997 or 2006 edition, the amount of flour had been reduced after several tests and retests. They didn't know why. "The recipe from 1975 was perfect," she says. She and John decided that there had been too much interference from too many recipe testers—literally too many cooks in the kitchen.

That taught them a few valuable lessons: "We took the stance that we would take nothing for granted," says John. "If we made a statement, we evaluated everything to make sure we were on solid ground or weren't leaving something out."

And when the time came for recipe testing, they did it all themselves or with the help of a few close friends they hired to work part-time.

The recipe-testing was in itself a chore. "The things that turned out to be difficult," Megan says, "are the things we thought were going to be easy." During the first few years of working on the book, they lived near Ethan in rural Tennessee, an hour from the nearest supermarket. "It definitely made grocery lists very consequential," says John. "If you forget something, you're screwed." (Later on, they moved to Portland, Oregon, where they still live. "From famine to feast," John jokes.) They lost track of the number of recipes they tested.

In the process, they began weeding out recipes, like shrimp wiggle, that no longer seemed applicable and adding new ones, like kao soi gai, that reflect what people eat now. (And there you have 90 years of American culinary history.) They added recipes from Megan's family and recipes they had invented themselves. They made sure not to get rid of undisputed classics, like Marion's banana bread. They revived recipes, like lemony butter wafers, that had been dropped between editions. They also consulted Ethan to make sure they weren't committing any unforgivable desecrations. The one they remember especially was Irma's sauerbraten recipe. "He had memories of it," Megan says. "We wanted to make it better." One thing they thought would improve it was including crushed gingersnaps as an optional ingredient, something Irma had been vehemently against. But Ethan was supportive. "I can't remember if he ever put his foot down about something," John says. "If he did, it ended up being not a big deal."

Now the book is finally ready to be released into the world, and they are excited and also terrified. But they are glad they continued the family tradition. "One of the things that was really great for me," John says, "is that I was never able to meet Irma or Marion, but I feel like I kind of know them in a way that would never have been possible even if I had met them, just by working on this book."

Khao Soi Gai (Thai Chicken Curry Noodles)

4 servings

Superlative comfort food from northern Thailand. Tender egg noodles and fall-apart chicken lurk in the coconut-curry broth; the optional crispy fried noodles add crunch. Add more or less curry paste depending on your tolerance for spice and the heat level of the curry paste you have on hand. Pickled mustard greens are an optional garnish here, but they add a welcome, tangy complexity to the rich broth. Made from a chunky, thick-leafed variety of mustard, these pickles are available at most Asian markets, either in small cans or plastic pouches (purchase the sour or "acrid" variety).

In a large pot of boiling unsalted water, cook until just tender:

8 ounces dried Chinese egg noodles or thin egg noodles, or 1 pound fresh wonton noodles

Drain, rinse, and drain again. Set aside. Heat in a large skillet or saucepan over medium heat:

2 tablespoons vegetable oil

Add and fry, stirring, until fragrant and slightly darkened:

2 to 3 tablespoons yellow curry paste or red curry paste, store-bought or homemade

Add:

4 chicken legs, thighs and drumsticks separated, or 2 ½ pounds bone-in chicken thighs

One 13 ½ ounce-can coconut milk

2 cups chicken stock or broth

¼ cup packed brown sugar or grated palm sugar

2 tablespoons curry powder

Bring to a boil, reduce the heat, and simmer until the chicken is cooked through and tender, about 30 minutes. Meanwhile, if you wish to have a crispy topping for the soup, remove a handful of the cooked noodles and divide the rest among serving bowls. Heat in a small, deep saucepan to 350°F:

(2 inches vegetable oil)

Thoroughly dry the handful of noodles and shape into four "nests." Fry one at a time, turning once, until crispy and golden, about 2 minutes. Drain the nests on a plate lined with paper towels. When the chicken is done, divide it among the bowls. Taste the broth and add:

1 to 2 tablespoons fish sauce, or to taste

Top the noodles with the broth and fried noodles, if using. Serve with:

Lime wedges

Thai fried chili paste, or sambal oelek

Thinly sliced shallots

Chopped cilantro

(Chile-Infused Fish Sauce)

(Chopped pickled mustard greens, see headnote)

Reprinted with permission from Joy of Cooking by Irma S. Rombauer, Marion Rombauer Becker, Ethan Becker, John Becker, and Megan Scott (Scribner)