What The Heck Was Shrimp Wiggle?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Everybody collects something, and for me, it's primarily dust and dog hair. Running a not-so-distant third, however, is my assortment of vintage cookbooks. Contrary to popular belief, the old-timey recipes found therein are hardly a catalog of horrors. Okay, so retro Jell-O salads aren't really my thing, but there are plenty of classic family dinners that deserve a comeback.

One recipe I've encountered a number of times but never had the slightest urge to make, however, is a concoction called shrimp wiggle. Not only is the name unappetizing, but the ingredient list doesn't look too promising, either. The dish consists primarily of shrimp in white sauce with peas, served over toast (eww, soggy), crackers, or rice. In the mid-20th-century convenience food era, some home cooks chose to use condensed soups such as cream of shrimp instead of the sauce, while others added ingredients like ketchup, tomatoes, or processed cheese (which is perfect for melting).

So what did this dubious dish taste like? I'm too much of a coward to provide a first-hand account, so you'll need to settle for second-hand impressions. Needless to say, these vary. Some think the dish quite bland, even comparing it to something you might eat in a military chow hall. Others, however, find it rather tasty, possibly because they've spiked the sauce generously with sherry.

Shrimp wiggle has an unsettled history with one classic cookbook

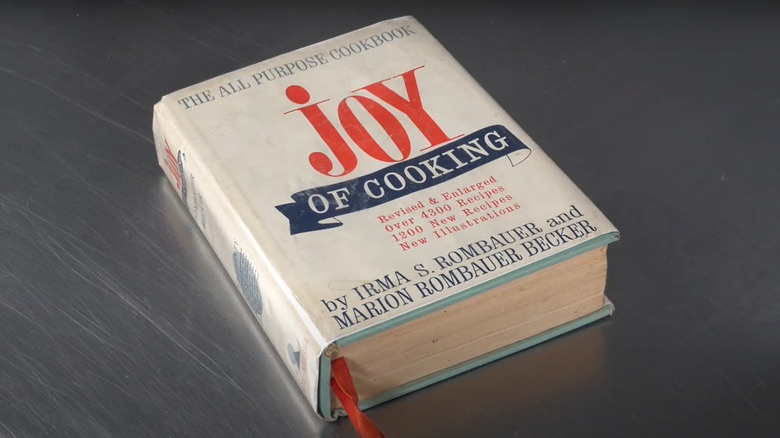

The very first mention of shrimp wiggle seems to have been in a book called "Chafing Dish Possibilities" that was originally published in 1898and authored by Fannie Merritt Farmer of "Boston Cooking School Cookbook" fame. The recipe is a rather simple one, calling for nothing more than butter, flour, milk, shrimp, and peas. By the early 20th century, the list of wiggles had expanded beyond shrimp to include lobster and chicken. In 1931, shrimp wiggle gained further legitimacy by being included in the first edition of the now-classic "Joy of Cooking."

Over the years, though, this dish has dipped in and out of revised JOC editions. The 1975 cookbook made no mention of shrimp wiggle, nor did the one that came out in 1997. In 2006, however, the venerable compendium brought back some of its older recipes, and shrimp wiggle once more made the cut. Alas, the reunion was short-lived, since by 2019, shrimp wiggle was again bounced from the newest "Joy of Cooking." This time, however, the editors at least offered an apology for its omission.

We have no idea how shrimp wiggle got its name

As far as anyone knows, there's no definitive etymology behind the term "shrimp wiggle," so that leaves us free to speculate. One rather obvious (and also kind of gross) hypothesis is that the dish was named for how shrimp can seem to wiggle as they hit a hot pan, but ... ick. Who'd want to cook it with this unpleasant image in mind? The alleged wiggling action also doesn't seem to apply to those wiggles made from chopped, cooked chicken and lobster.

It's more fun to think that "wiggle" was simply a cute name dreamed up by turn-of-the-(last) century college girls as they made midnight feasts in their dorms (this was seen as rather daring rule-breaking 100-plus years ago). The term "wiggles" was applied not only to quickly-cooked meals heated in chafing dishes over illicit cans of Sterno but also to the impromptu parties surrounding their preparation. There are a few flaws with this theory, however, since the name "shrimp wiggle" seems to have been coined by the 30-something Fannie Farmer some 16 years before Sterno was even invented. Without a Ouija board, we're unlikely to learn why she chose this particular name for her recipe, but then again, it really doesn't matter. The true mystery of shrimp wiggle is whether or not you're brave enough to try it. If so, you're one up on me.