Have The Germans Figured Out The Secret To Great Asparagus?

Will this one trick finally convert me to the religion of Spargelzeit?

If you live outside of Germany, you probably don't spend much time thinking about asparagus. It's a vegetable, it's grown in spring, it makes your pee smell weird. What else is there to say?

Germans, on the other hand, spend 10 months a year eagerly anticipating the slender vernal window known as Spargelzeit, or "asparagus time." By "asparagus," they mean white asparagus: not the delicate green stalks Americans know, but thick ivory spears grown beneath dirt mounds to inhibit chlorophyll development, their appearance ranging from kinda phallic to X-rated.

During its peak season, which runs from around Easter to late June, Spargel is everywhere. Michelin-starred restaurants and hole-in-the-wall curry joints offer special menus devoted to it. It's reverently displayed in supermarkets alongside shelf-stable cartons of Hollandaise sauce. The towns where it's grown hold festivals in its honor, complete with parades and the crowning of a "Spargel queen."

I might get my German residency revoked for saying this, but... I don't get it. Every year, I make like my countrypeople and pick up a package of gleaming, farm-fresh white asparagus. Every year, I dutifully boil it and choke it down, doing my best to ignore the bitter aftertaste.

And every year, I can't help but wonder: is it the Spargel, or is it me?

The challenge: Tame the savage asparagus

No matter the color, asparagus is a finicky vegetable. From the moment it's picked, its sugars start converting into starches; eat it more than 48 hours after harvest and you're not getting it at its best. It's also high in a type of sulfuric compound that's called, appropriately enough, asparagusic acid. That chemical is responsible for the, uh, unique aftereffects of asparagus (memorably described by Proust as "transforming my chamber pot into a flask of perfume"), as well as the acrid taste that can emerge when it's cooked.

White asparagus in particular harbors more bitterness, whether because of its lack of chlorophyll, its fibrous outer layer (which can ruin the vegetable's taste and texture if it isn't peeled off before cooking), or simply its sheer size. Unlike the green kind, it's bred to be as thick as possible; the more it resembles a chode, the more highly Germans prize it.

Whether white or green, the internet is full of tips on how to tame the savage Spargel. Plunge the asparagus in ice water after it's boiled. Cook it with vinegar, with lemon juice, or with chicken broth. "Boil for 27 minutes in lightly salted water, throw away the water, throw away the asparagus, then go out for some real food and beer," suggests one internet forum user.

The hack: Boil asparagus with bread

This year, for the first time, I noticed that several German recipes mentioned one peculiar tactic for making asparagus taste better: throw in a stale roll or piece of bread while it's boiling, and the bread will "absorb" any bitter flavors.

My first reaction was skepticism. How does the roll know what to absorb? It's already been proven that potatoes won't "absorb" the excess sodium in an over-salted soup, and that most flavors in marinades don't get "absorbed" by whatever's marinating. Germans themselves seemed divided on the trick's efficiency. On one cooking forum, a handful of posters swore by the addition of bread (or potatoes) to their Spargel pots; others hadn't heard of it or said it made no difference.

Nobody, however, had done a side-by-side taste test. And so, in a last-ditch effort to understand what all the fuss was about asparagus-wise, I decided I would be the first.

The test

As a guideline, I used this recipe from the Berlin restaurant Kurhaus Korsakow (as dictated to my former employers at the English magazine Exberliner), forgoing the hollandaise so as to allow the pure flavor of the Spargel to shine through.

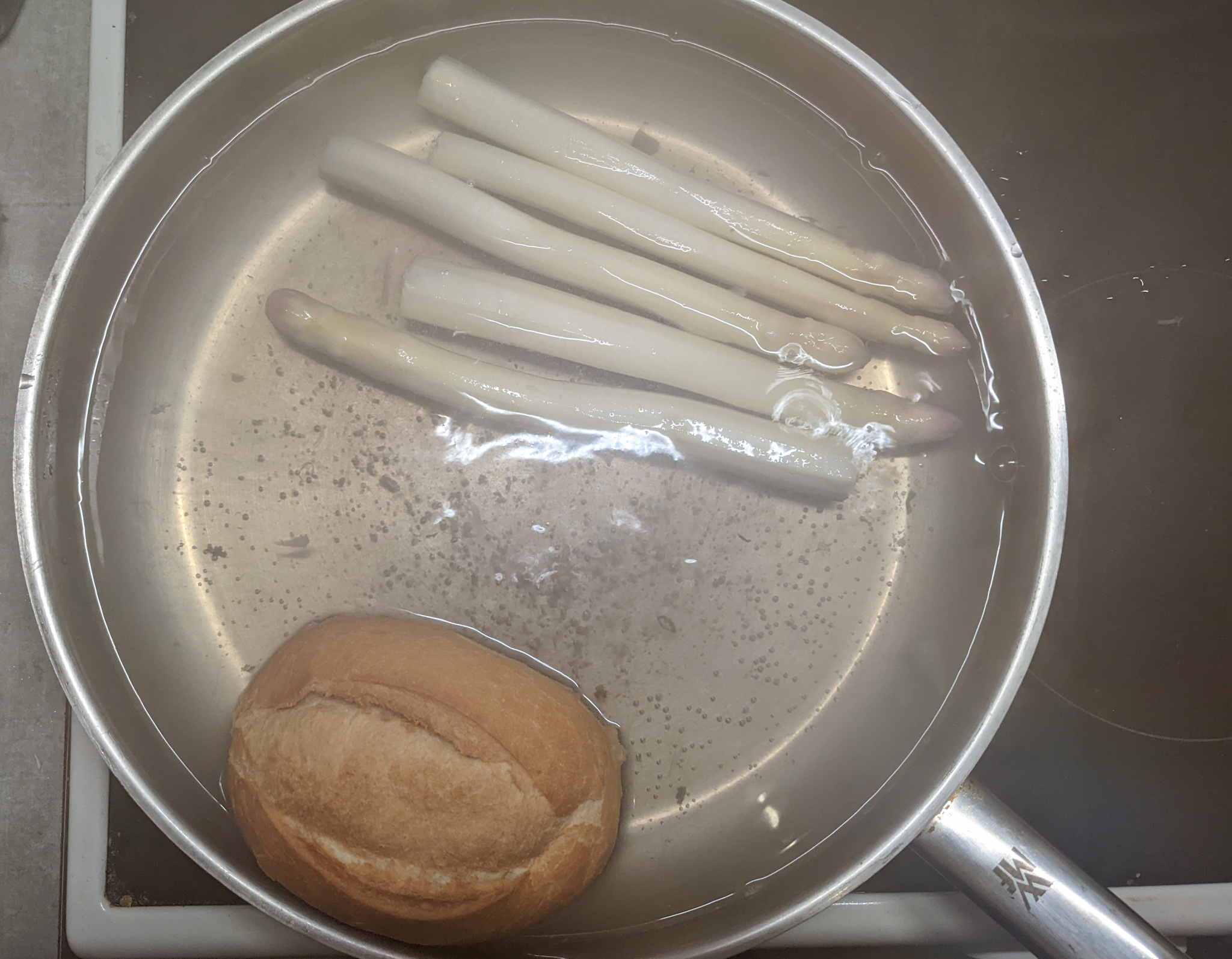

I got all my materials ready: half a kilo of local, organic white asparagus; half a kilo of the green stuff, just for the hell of it; a bread roll from the half-price grab bag my neighborhood bakery sells at the end of every day. I fastidiously trimmed and peeled the white stalks, divided the peels and trimmings between the two pots of water I had simmering on the stove, then strained them out after a minute. Next came the asparagus, plus "a little salt, a pinch of sugar and a splash of white wine." Finally, in one of the pots came the crowning touch: a white roll, which bobbed around half-submerged like a U-boat.

I cooked the white asparagus for 15 minutes, then took it out and boiled its green cousin for 5 minutes, by the end of which the roll was fully saturated and partly disintegrated. I placed the stalks on either side of a large plate, making sure to label which was the control and which had been cooked with the bread.

The results

I tried the white asparagus first. A stalk from the control batch tasted fine at first, then smacked me with the same nasty aftertaste I was used to.

Next, one from the "roll" batch. Could it be that it tasted just the slightest bit sweeter? A second bite from each batch confirmed my suspicions: The asparagus that had been boiled with the bread really was milder. With some melted butter and a squeeze of lemon juice on top, it was even enjoyable.

Surprisingly, the effect was even more pronounced with the green asparagus. Despite it having been boiled for much less time, the batch from the bready water had a distinct sweetness that the control group lacked.

I couldn't believe it. In my head, I started drafting an article with the headline, "You've been boiling asparagus wrong your entire life." But something didn't feel quite right. Returning to the stove, I fished out the half-dissolved bread roll and transferred it to a plate, where it lay dripping with lukewarm asparagus water. I girded myself and took a bite.

It wasn't bitter at all, as it would've been if it had performed its supposed absorption duties. Instead, it was sweet, similar to the asparagus. The truth began to dawn on me as I sampled the water from both pots. Rather than go about this experiment with Kenji-like precision, I'd put a larger "pinch" of sugar in with the bread roll. More sugar, sweeter Spargel, duh. My results were completely invalid.

The conclusion

Or were they? Most German asparagus recipes include sugar, but it's never mentioned as a "hack" the way bread rolls are—you just add it, no questions asked. But it seems adding more sugar is the true key to neutralizing the vegetable's bitter compounds, replacing any natural sweetness that was lost between harvest and dinnertime, and transforming Spargel into a suitable schnitzel accompaniment. So maybe you have been boiling asparagus wrong your entire life.

What's nifty is that it works on the green variety as well, meaning that if you suddenly got a hankering for asparagus in the middle of October and had to use the imported stuff from California or Peru—not that you should do this, Spargelzeit is sacred!—but if you had to, a quick boil with some salt and a healthy sprinkle of sugar might help breathe new life into those sad, out-of-season stalks. And, hey, toss in an old bread roll while you're at it. Why not? I can't promise it'll help, but it won't hurt.