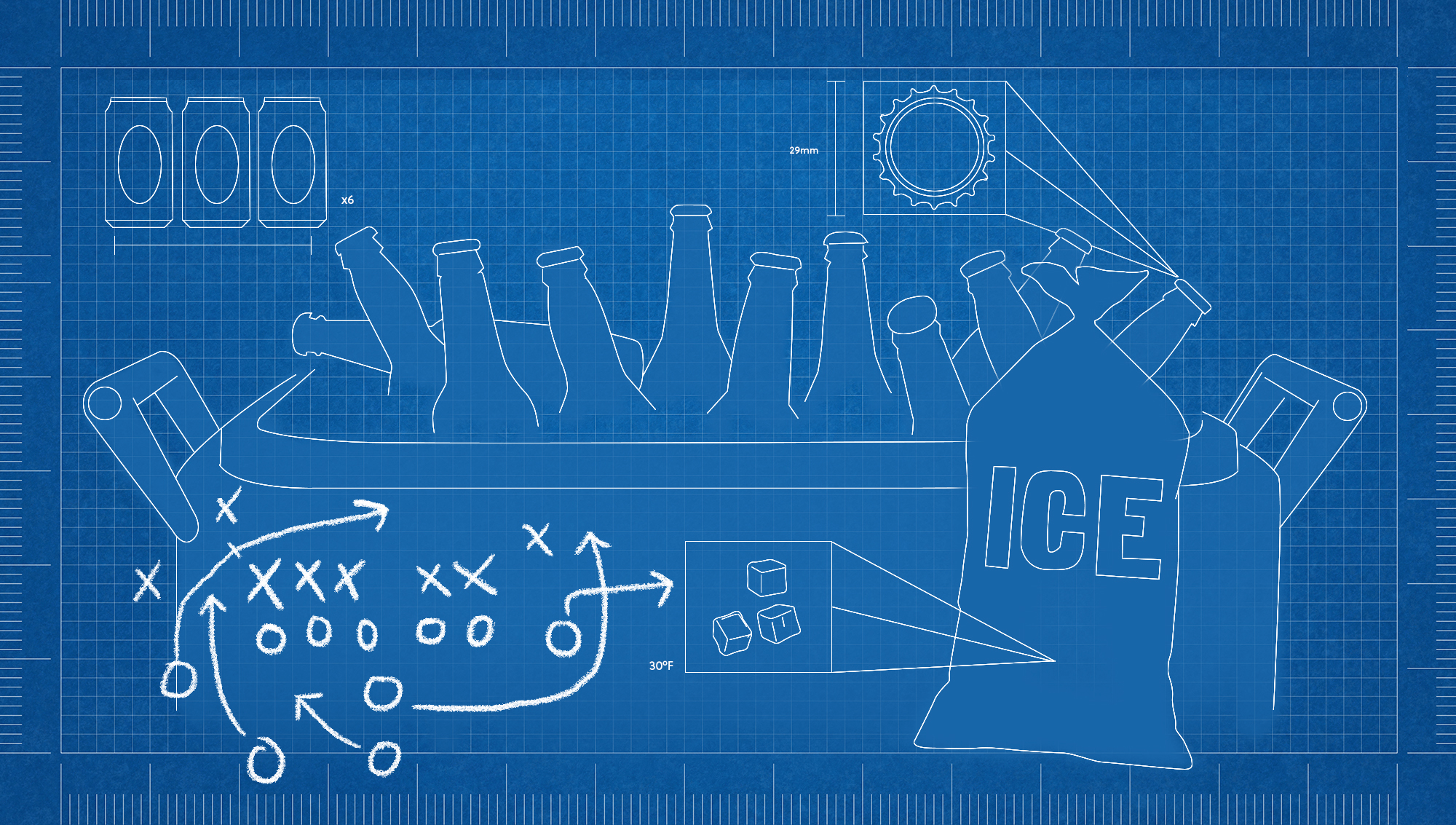

How To Assemble The Perfect Party Beer Cooler

Shopping for a Super Bowl party must have been easier in the decades before craft beer took hold: Pick up a few cases of your domestic lager of choice, throw in a bottle of white zin for the ladies and call it a day. Now, even the most mainstream of grocery stores have dozens of beer options in so many weird fruit flavors that party prep turns into something nearly quadratic.

There are variables. A host must take into account not just the number of people attending, but who likes which beers, who drinks more than others, who will opt for wine or just iced tea, what food is on the menu, etc. I spend an inordinate amount of time planning my own party refreshments because my friends know I love beer and expect to find a well curated fridge at Casa Bernot.

But let me do the hard work so you don't have to. I've distilled years of beer party hosting into these guidelines that will ensure you greet your guests with a varied and practical selection of barley-based beverages. Tweak these to your own personal preferences, and may God rain hot fire on Tom Brady this Sunday.

Chill your cooler

On Saturday night, stick your empty cooler on a back porch or in your garage, if your weather is cold enough to chill it.

Calculate ice requirements

In the winter, you can get away with a pound of ice per person. For this guide, let's assume a party of 10 beer-drinking adults. You'll need two 5-pound bags of ice.

Calculate beer consumption rates

Super Bowl games historically run between 3.5 and 4 hours long, so I've calculated a 4-hour drinking window here. Standard party advice suggests guests will drink two drinks per hour for the first hour, and one drink per hour after that. This formula also assumes that you're providing all the beer. Giant disclaimer: Drinking rates vary; some people will only have a couple beers throughout the whole game while others will constantly have a drink in hand. Because this is the Super Bowl, I'm basing my calculations off two 2-drink hours and two single-drink hours per guest. That shakes out to six beers per guest for approximately 60 beers total. (No guests should drive themselves home.)

Break beer down stylistically

Because I often don't know everyone coming to a party—plus-ones, friends of friends, etc.—I like to err on the side of approachable, easy-drinking, non-extreme beers that please a range of tastes. People should, I think, be focused on the game, the food, and the halftime show, rather than picking apart the raspberry-lime-whatever-flavor in their hand. Really finicky drinkers will bring their own bottles, anyway. Here's your shopping list:

- 12 domestic light beers: These are for the people who only drink domestic light beers, and for the craft drinkers who get palate fatigue and just want a Coors Light by the end of the game.

- 3 fun stouts: If you have more beer-nerdy drinkers coming over, it can't hurt to pick up a few 22-ounce stouts with fun flavor adjuncts like chocolate or chili or peanut butter for sharing.

- 18 craft pilsners: If this was the Kate-only party, the whole cooler would be full of well-made, low-ABV, balanced pilsners. They have more flavor (and slightly more alcohol) than light beers, and taste great alongside pretzels, tortilla chips, and mild cheese. They're no-fuss, easy-to-drink, and not distracting.

- 12 IPAs or pale ales: People claim that hoppy beers and spicy foods like wings or salsa are so great together, but I personally think that's a bit of beer-world cliche rather than actual gospel. Still, Americans love their hops, so have two six-packs of these around. (I'd opt for a classic pale ale like Sierra Nevada rather than roll the dice on a small-batch IPA I've never had, but you do you.) A party shouldn't need more than a couple six-packs; likely the drinkers that opt for IPAs will only have two or three each before they want to switch to something less bitter.

- 18 "brown beers": A friend recently asked what my favorite winter beer styles are. I listed off brown ales, schwarzbiers, amber ales, Vienna lagers... which can all be summarized as malt-leaning brown beers. These are, for me, the quintessential Super Bowl beer style: smooth, moderate in alcohol, fantastically food-friendly, and clean. Anything amber or brown that isn't a porter or stout is a great candidate for filling the bulk of your beer fridge.

**Note: This adds up to 63 beers, not 60 as mentioned above, but that's because I wanted to keep things in six-pack quantities except for the the three large-format stouts.

Pack your cooler

Spread a layer of the domestic lager bottles/cans at the bottom of the cooler with a layer of ice over them. These need to be kept the coldest; no one likes a warm-ish Bud Light. Stack the "brown beers," pilsners, and pale ales/IPAs next. Keep the stouts outside the cooler (if your beer is outside), as you don't want to fish through everything else to find them. If you're in a cold-enough climate, it'll keep them chilled. Before serving the stouts, bring them inside to room temperature and let them warm up for 10-15 minutes before serving. Cold is the enemy of beer flavor; warming a stout slightly is the beer version of decanting.

Don’t sweat the glassware

Even though I am an advocate of proper glassware in most beer-drinking situations, I think sporting events get a pass. Glasses and people reaching for dip every three seconds tends not to work out. I wouldn't get too worked up with pilsner glasses and nonic pints and snifters; aside from the large-format bottles that will need to be poured into smaller glasses, most people will probably drink out of bottles and cans. Have a few (recently rinsed) all-purpose pint glasses ready just in case someone asks for one.

Toast!

You did it. Now toss one back and make sure the potato skins aren't burning in the oven.