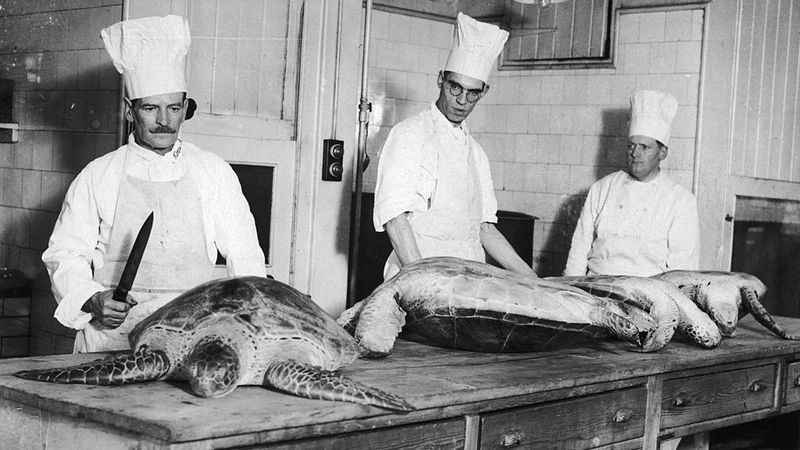

Why Have Americans Stopped Eating Turtle?

America has a food diversity problem. Chicken, pork, and beef account for many of the animal proteins found on our dinner table—the product of decades of agricultural industrialization—and this has left us with cheaper but more limited options at the butcher's counter. Once a year we all sit down to eat turkey, but when was the last time you had snipe, mutton, or rabbit?

Perhaps the mightiest protein to fall out of favor, though, is turtle. From the earliest colonial days, Americans were smitten with this four-legged reptile, and turtle soup—its most common preparation—was a restaurant norm into the 1970s and '80s, a dish exuding luxury status. But today, outside of pockets in Louisiana and Pennsylvania, turtle has almost completely disappeared from our diet. What happened?

First, some historical context: During the Age Of Exploration, European sailors to the New World encountered bounteous populations of green sea turtles in the West Indies, and marveled at the outsized role they played in everyday life there. Enormous specimens weighing hundreds of pounds were sold live or dead at the market, and offered in every form: whole, butchered, dried, and roasted. The turtle was a staple of the Caribbean diet, ideal for its rich meat, large shells, and the cooking and heating oil rendered from its fat.

Sailors realized that this curious creature—they'd find thousands bobbing in the open water—could be used as a literal lifesaver; turtles could be held in salt water pits on the ship as a safeguard against future food shortages or shipwrecks, and the animals would last for months without feeding. Some of these turtles inevitably survived the trip back to Europe, and they were presented as gifts to royalty or sold to adventurous aristocrats.

Among the exploring kingdoms, the English were by far the fondest of turtle as a delicacy. Initially, commoners could not afford an imported turtle of their own, and interest in turtle dishes spread secondhand through stories in travelogues, newspapers, and books. Cookbooks of the 1700s—themselves a relatively new entertainment form—described elaborate preparations, even if most readers were never expected to have access to the ingredients themselves. The act of eating turtle was beside the point. Instead, tales of the fragrant spices, indigenous peppers, and mammoth reptiles that flavored recipes like "Turtle Soup In The West Indian Way" represented exotic escapism.

As the turtle trade matured through the 1800s, access expanded, and the middle-class was finally let in on the action. Select London taverns offered bowls of soup regularly, and one—aptly called The Ship And The Turtle—stocked an aquarium full of live specimens in the dining room where guests could eye their next meal. For those who managed to secure their own wriggling animal, beer halls offered to handle the dirty work of butchering and cooking, meaning fancy dinner party hosts could provide their guests with catered bowls while sparing their home kitchens.

While turtle soup in England may have been a luxury made from giant green sea turtles, American colonists found great numbers of smaller turtles and tortoises, enough to make it an accessible dietary staple. These native varieties were plentiful, tasty, and easy to catch, making haute cuisine as close as one's own backyard.

The founding fathers were big fans—John Adams and George Washington both celebrated independence with hearty bowls of turtle stew—and early frontiersmen fought off hunger by catching turtles out of streams as they pushed west (along with other bygone snacks such as beaver and river eel). Northern states celebrated the diamond terrapin, while Southern states were home to grand alligator snappers. The Texas Gulf Coast even provided a domestic source for the giant green sea turtles of yore.

By the mid-1800s, turtle was quintessentially American cuisine. Home cooks and restaurants could buy canned turtle meat at the grocers, and the animal even cycled back onto high society menus as a staple of gentlemen's social clubs. When the famous Parisian chef Auguste Escoffier came to New York in 1908 to open his second Ritz Hotel, a star dish on the inaugural menu was Terrapin À La Maryland, a Baltimore-style preparation of diamondback sautéed in a sauce of Madeira wine and sweet cream.

What's the fuss about?

"It's one of my favorite ingredients to cook with," says Cody Carroll, chef and co-owner of Sac-A-Lait restaurant in New Orleans. "Most proteins are desired for their flavor, but there are a few ingredients that are favored mostly for their texture, like calamari." Turtle, interestingly, seems to fall into both categories. "Turtle has the advantage of having an incredible meaty, beefy flavor with an extremely unique texture... think alligator or squid."

Beyond the meat, a lot of turtle's unusual taste comes from its shells, bones, and fat. Simmering these scraps produces a rich and gelatinous stock, and explains why turtle soup has become the animal's most famous preparation. "The reason why you really only find turtle in soups goes back to how difficult it is to clean," Carroll says. "A turtle is almost all shell and bone, so after dressing it, you are left with a bunch of small irregular-shaped pieces of meat. This prohibits any possibilities of serving it 'as is' like a beautiful steak."

Don't have a turtle of your own to taste? Consider the Victorian favorite mock turtle soup. To mimic the thick, gummy stock, boil a calf's hooves and head—skin on, brains out—and shred the cheap meat that falls off the bones. For the true historical throwback touch, serve it in a hollowed-out turtle shell and add meatballs in the shape of turtle eggs. Remember, most diners of this era had never tasted the real thing, only read about it. Flavor accuracy is ancillary.

But turtle's once-vogue status is now but a bygone fad. Open a restaurant menu today and turtle is nowhere to be found. Where did this food fit for both kings and commoners go?

The beginning of the reptile's fall lies in its own popularity. Turtles are long-lived creatures that reproduce slowly, and demand for the animal pushed populations to the brink. In the places where fisherman once pulled hundreds of animals out of the river each day, numbers dwindled to nearly zero. Today many species are threatened or endangered, with harvesting prohibited or restricted.

At the same time, two other circumstances hastened turtle's demise. First, since nearly all turtle soup recipes call for fortified wine—sherry or Madeira typically—America's "noble experiment" forced the traditional preparation into hiatus and out of diners' minds. "Prohibition in 1919 put an end to the public consumption of dishes employing fortified wines," writes David S. Shields in his book Southern Provisions. "When Prohibition was repealed, the taste for the old Chesapeake classic had declined to the extent that few temples of haute cuisine restored it to the menu. Even in Baltimore and Washington, D.C., it gave way to oyster stew and clam chowder in popularity."

Shortly thereafter, turtle suffered another image setback. Herbert Hoover's 1928 presidential campaign touted the slogan "A chicken in every pot and a car in every garage"; America entered the Great Depression the following year, and those down on their luck found themselves with neither. In the South, the poorest turned to the native gopher tortoise as a source of protein, calling their catch "Hoover chicken." When peace and prosperity in America returned, turtle retained the stigma of those hard times.

In the intervening years, turtle's fade from our culinary memory has been gradual, but constant. "I recall seeing turtle meat in markets in only two cities—Baltimore and New Orleans," says Southern Foodways Alliance director John T. Edge. "It's surely on the wane." And the same trend is borne out in restaurants. Searching the New York Public Library's "What's on the Menu?" database—a collection of nearly 18,000 menus—reveals 2,700 hits for "turtle." The earliest bill of fare dates to 1851, but the vast majority—nearly three quarters—are from turtle's heyday of 1890 to 1920. Although the database is admittedly incomplete (especially in the modern era), the search turns up only a handful of turtle offerings in the 1960s and '70s, and nothing after 1989.

Today turtle persists in the U.S. mostly as a regional novelty in places like New Orleans. Chef Carroll of Sac-A-Lait grew up fixing Louisiana game and celebrates turtle as part of his heritage, but acknowledges there are few working with the animal. "There is very low supply and soaring costs. Turtle meat is one of the hardest meats to find."

This scarcity serves to reinforce its niche status. "I believe that its popularity outside of New Orleans has fallen off for several reasons," Carroll said. "It's a combination of how expensive it is, how time-consuming it is [to butcher and prepare], and chefs' lack of knowledge as to how to handle it and cook it."

Could turtle soup make a return? Turtle remains a popular dish in Asian cultures (especially in places touched by British colonialism), and farming advances mean that sustainable sources are available, so long as diners are willing to pay a premium. But since turtle soup is more than 30 years removed from most diners' and chefs' memories, there are few advocates. Are we one David Chang Instagram post away from a revival, or have Americans turned away from turtle for good? More likely, neither outcome is true. Like the tortoise of Aesop's fable, turtle soup will probably keep up its slow and steady march, neither flashy nor trendy—forgotten but not out.