When Roadkill Becomes Dinner

In a Lyft on my way to a dinner party, I feel the driver slow down as two whitetail deer approach the side of the road. The small does freeze, ears perked and saucer eyes watchful in the crepuscular light. Our car creeps by and eventually accelerates to leave them in the rearview.

Municipal deer are a common sight in Missoula, Montana, but tonight they're discomforting. I'm en route to my friend Bryan's house for a venison dinner made from roadkill that he salvaged; just a few weeks ago, he picked up a juvenile deer someone else had recently hit on the same road I'm traveling. It's legal under Montana's 2013 "roadkill bill," formally called the Vehicle-Killed Wildlife Salvage Permit, which allows the collection of deer, elk, moose, and pronghorn antelope killed by collisions with vehicles. In the two years following the bill's passage, the Associated Press reports the state issued 1,747 animal salvage permits.

It's not just Montana scooping up its street meat. Earlier this year, Oregon passed a law allowing for deer or elk salvaging, and similar statutes are on the books in about 20 other states, including Washington, Colorado, North Dakota, Indiana, Illinois, New York, and Tennessee. Morality of all this aside, as I watch the taupe-colored deer recede into the twilight, I wonder, "OK, but how is this going to taste?"

"So I pull over to the side of the road, get out of the car and I realize 'Oh damn, the deer isn't dead yet.'"

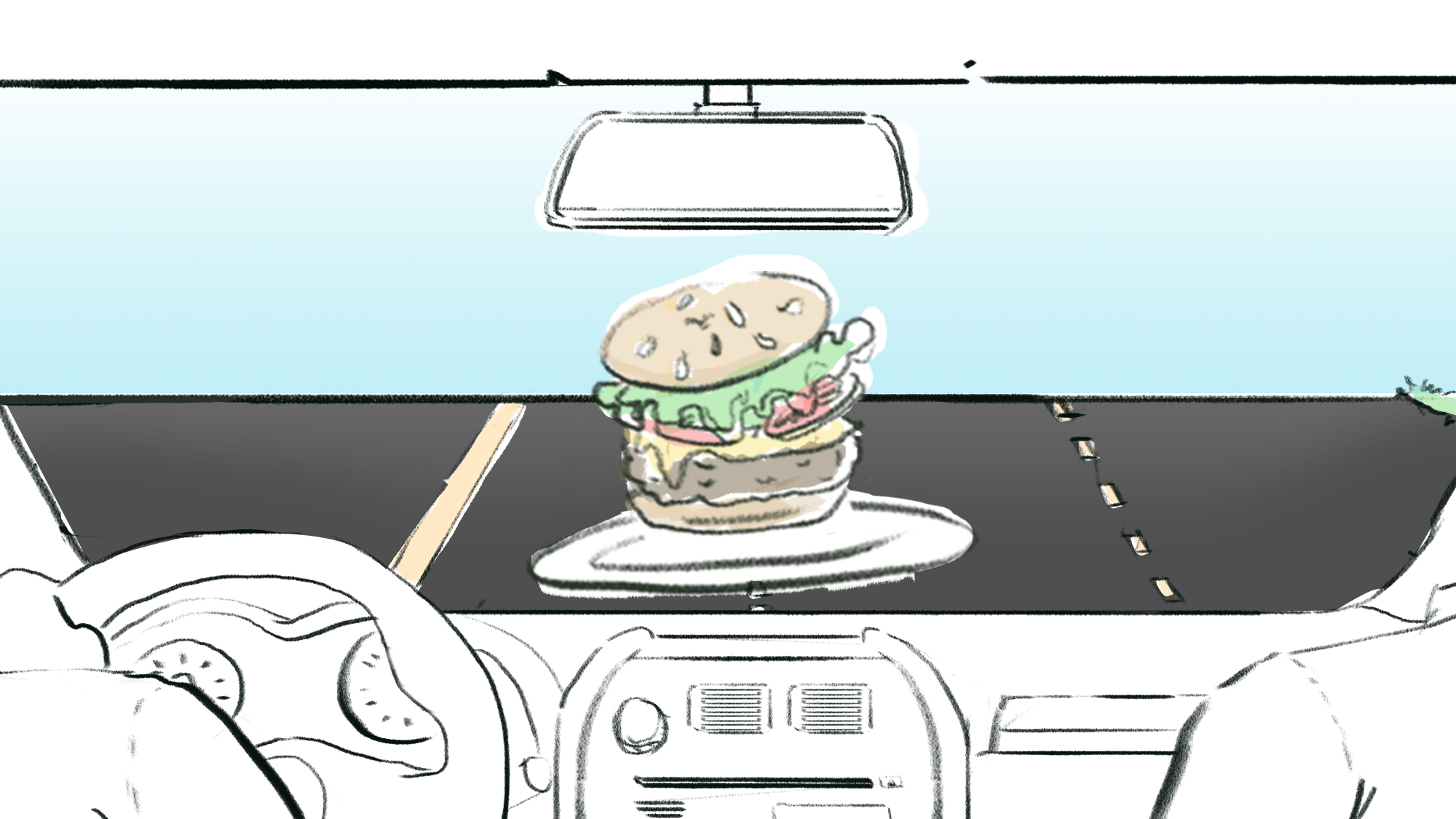

The six-person dinner party listens with rapt attention as Bryan recounts the story we all want to hear: the story of how the deer went from pavement to pick-up truck. We're still eating, though, which makes for an awkward pause as we glance down at our plates. On the menu tonight are Sloppy Does, bun-encased sandwiches filled with a seasoned, spiced and savory blend of onions, tomatoes, and Bambi.

Wait—not dead yet?

"Right. I get out of my truck and I see the deer's really badly hurt, I mean, this thing can't get up or move."

It's hard to convey a person's tone in written form, so I want to be clear that Bryan is telling this story with the no-nonsense compassion of a person who's hunted for most of his life. He knows when an animal is dying, and he's not interested in that process taking any longer than it has to. As an outdoorsman (and a Montanan), he also happens to carry a rather sizable knife in his truck. So he headed back to the truck, grabbed it, and returned to put the animal out of its misery.

Technically, this is illegal. And Bryan knew that. The roadkill bill explicitly states that the animal die as a result of a collision: "The permit does not include other mortalities." If you set out to kill an animal, that's hunting, and the state has an entirely separate licensing system for that. Under the salvage permit, you're only entitled to take an animal that's already dead, and you have to call state Fish, Wildlife & Parks to report it within 24 hours. At that point, they'll issue you the permit by phone.

But standing over the panting animal, Bryan couldn't just watch it suffer. If you, like me, grew up in an area of the country where hunting wasn't terribly common, you can wrongly assume that hunters don't have compassion for the animals they kill. It's quite the opposite; most have a wealth of respect for animals, having so closely observed the animals in nature for lengths of time. I've never fired a gun, and the closest I've come to experiencing the death of a living thing at my own hands was fishing with my family and subsequently filleting our catch. Though I'm okay with eating meat, I of course would want the animal's pain in the process of getting to my plate to be as minimal as possible. So it's a relief to hear Bryan admit that he was moved by the sight of the twitching, badly injured deer. He quickly plunged the knife into its neck, ending its breathing.

He dragged the whole animal to the back of his truck, careful not to leave anything behind. The roadkill law states: "Parts or viscera cannot be left at the site. To do so is a violation of state law and would encourage other wildlife to scavenge in a place that would put them at risk of also being hit."

Bryan returned home with the carcass in the back of his truck. His wife looked at him and noticed the distracted, serious expression on his face.

"You look like you're about to tell me there's a body in the car."

No one at the dinner flinches at the story. Present around the table are a fish biologist and two former national parks employees, so no one's squeamish about the natural world and its circle of life. (The four children seated at the kid's table presumably don't know where dinner came from.) As the newest Montanan, I'm still teased for being a city-slicker and having an out-of-state area code. Game meat, let alone roadkill, isn't super-familiar territory for me. But on this issue of roadkill ethics, we're all in agreement. Yes, we're down with what's for dinner.

An adult deer can yield 150-plus pounds of lean, hormone- and antibiotic-free meat, the kind of game you'd pay top dollar for in a restaurant or butcher shop. The meat does little good, except perhaps for turkey vultures, when left to spoil on the side of the road. If humans were responsible for an animal's death, it seems fitting that we find a use for its meat. So there's just one question left to answer: How good can roadkill taste?

For the record: very good. Bryan prepared this deer meat by skinning it, butchering it, sautéing it, and finally canning it to ensure a shreddable texture and a long, shelf-stable lifespan. That last part is key, because a large animal like this can yield more than 10 quarts of stew meat.

For this particular dinner, he opened up the canned venison and mixed it with a sloppy Joe sauce of tomatoes, onions, cumin, chili powder, Dijon mustard, red wine vinegar, ketchup, brown sugar, and bacon (for good measure). The sauce is tangy and sweet, the meat tender but lean. It makes for a delicious sandwich, nestled on an onion bun and garnished with sweet pickle slices.

If you didn't know its origins, the spicy, fragrant sauce-covered meat could really be anything—venison from a butcher or ground beef from the supermarket. It hardly looks like meat from an animal, just food. That's why this dinner, and the story told over it, changes the parameters: I'm confronting the real, not-so-long-ago life of this particular animal. While eating, I didn't have any transcendental moment wherein I came to understand the oneness of our universe, but I did think, "Hey thanks, deer. I appreciate your life and am grateful for it."

Eating roadkill meat is, to me and many others, a worthy use of an animal's body, and a silver lining to its death at the hands of someone's Subaru Outback. The roadkill legislation didn't seem to generate too much controversy at the time of its passage in Montana; PETA, of all organizations, actually campaigned in favor of the roadkill salvage law, arguing it's "meat without the murder." This frames it as opportunistic food gathering, a passive way of attaining meat that doesn't involve the purposeful killing of an animal.

My comfortability eating this deer didn't make me want to strap a Winchester to my back and head for the hills—I'm still not sure how I'd fare when confronting a live animal through a scope. But it asked me to consider the life and death of the animal on my plate, an animal that not so long ago was approaching the road my Lyft driver had just driven on. In a less industrialized food system, we'd think about every meatloaf or rib roast or chicken parm this way. Even when I'm not eating Sloppy Does, it would behoove me to approach each plate with the same level of consideration.