The Surprisingly Lofty History Of American Butter Sculpting

The most famous butter sculpture of the 21st century—the annual butter cow at the Iowa State Fair—exists for a number of reasons: because cows are synonymous with Iowa, because the enormous cow reliably thrills fairgoers, and because it's good publicity for the dairy industry. But there was a time when American butter sculpture existed for a much simpler reason: the human need to create. The 19th century was an era that valued ingenuity and resourcefulness. If you were an artistically inclined Arkansas farm wife without access to modeling clay but daily performed the chore of butter-making, you used what you had.

Caroline Shawk Brooks wasn't always an Arkansas farm wife, although later in her life, as butter sculptor scholar Pamela Simpson writes in her book Corn Palaces And Butter Queens: A History Of Crop Art And Dairy Sculpture, she would play down her origins as a Cincinnati girl who'd had some art training; the story of the simple "country milkmaid" made much better copy. Brooks began sculpting butter, she liked to say, in 1867, "the year the cotton crop failed," as a way of earning extra money. In those days, it was common for farmwomen to press their butter into molds to form distinctive shapes—remember Ma Ingalls' pretty strawberry butter press in Little House In The Big Woods?—but Brooks was more ambitious. At first she worked small, with faces and animals, but then a large bas-relief she carved for a church fair led to her first commission: a sculpture of Mary, Queen Of Scots. Later that year, she created the work that would make her famous.

Dreaming Iolanthe was based on King Rene's Daughter, a popular 19-century play by Henrik Hertz about a blind princess who falls in love and begins to see. Brooks's sculpture depicted the princess just as she is about to wake up and see the world for the first time. Brooks packed the sculpture in ice so it could sit out on and devised a way to create a plaster mold so she could recreate it if necessary. She brought it back with her on a visit to Cincinnati, Simpson described, where her friends and acquaintances were duly impressed; two thousand other people paid 25 cents apiece to see it. One of Brooks' friends, Lucy Webb Hayes, wife of Rutherford (governor of Ohio and soon-to-be-president), arranged for it to be displayed in the Women's Pavilion at the 1876 Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia, where Brooks also gave a demonstration of her sculpting technique.

Visitors from all over the world came to see Dreaming Iolanthe. "In considering this work," wrote the editors of Frank Leslie's Illustrated Register Of the Centennial, "the difficulties attached to the employment of such a material should be taken into account, while it must be conceded that, whatever material the artist employs, the work itself is one exhibiting a high degree of talent, a fine ideal feeling, as well as exceeding delicacy and brilliancy of manipulation." In other words, despite the medium, it was art.

Caroline Brooks never went back to Arkansas. She studied in Europe and then moved to the east coast, where she sculpted in more conventional materials. But she remained true to her roots, Simpson writes, and always used butter for her preliminary models.

At the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, many of the state pavilions had butter sculptures to display their agricultural abundance and prosperity, and many of them were done by women. Butter was a good medium for women, (male) critics agreed; they had a special affinity for it. "Women were the ones in charge of butter making during this period," Simpson notes in her book, "and butter itself seemed to have 'female' characteristics of domesticity and delicacy." Brooks herself helped cultivate this impression: When she gave her demonstrations, she made a point of using the tools of a butter-maker, not a sculptor. Butter sculpture wasn't "real" art, and therefore female butter sculptors were no threat to "real" male sculptors who worked in stone and bronze.

In an essay about feminism and butter sculpture for the Women's Art Journal, Simpson observed that although Brooks never publicly commented on the role of women in the arts or said anything overtly feminist, she made a practice of sculpting strong women—Lady Godiva, Queen Isabella, George Eliot, the suffrage leader Lucretia Mott. Female scholars later praised her for opening doors for other woman artists.

The butter industry changed when more Americans began living in cities and buying commercially produced butter instead of churning their own at home. The commercial dairies grew into conglomerates. By the end of the 19th century, Simpson writes, butter was a huge business and under threat from margarine, which had arrived from France in the 1870s. The butter companies considered various advertising strategies and hit on butter sculpture. What better way for them to show off their product in all its bright yellow glory?

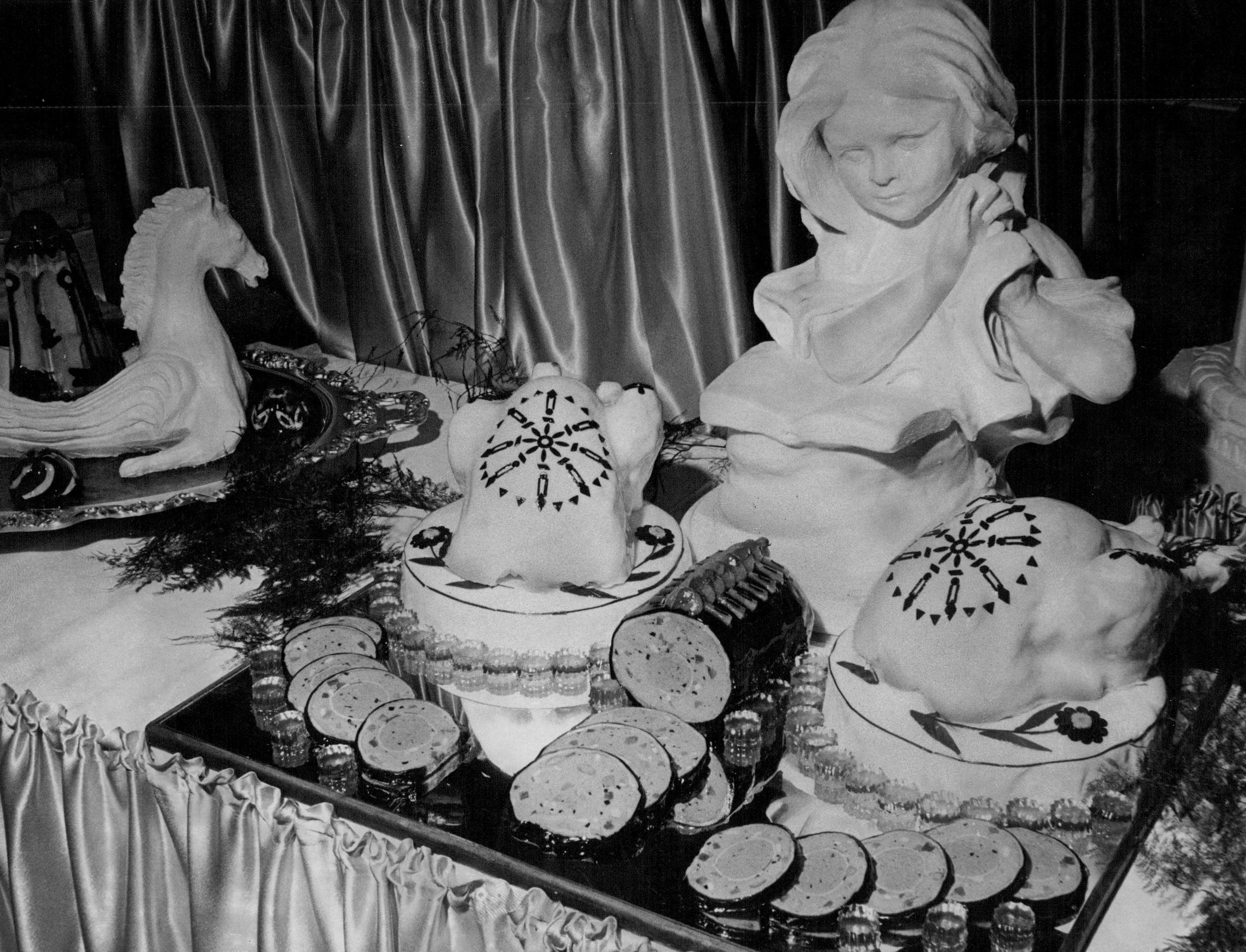

The 1901 Pan-American Exposition in Buffalo was billed as completely electric: A City Of Light. But also a city of refrigeration, a perfect opportunity to create some gargantuan butter sculpture. Minnesota, the self-styled "Bread And Butter State," commissioned John K. Daniels, a professional sculptor who usually worked in stone, wood, and bronze. For $2,000, Daniels was willing to work with butter to create a replica of its new Cass Gilbert-designed statehouse. Daniels and his brother/assistant Hacon spent six weeks in a glass box chilled to 35 degrees working 15-hour days on the sculpture, which was, in the end, 11 feet long and five feet four inches tall.

Thus began what Simpson calls "the golden age of butter sculpture," which ended with the food shortages of the Great Depression. The first butter cow appeared in 1903, not in Iowa, but at the Ohio State Fair. It appeared not as a vehicle for artistic expression but as an advertising ploy in the ongoing war against margarine: the long-forgotten sculptor was the winner of a contest sponsored by A.T. Shelton & Co., distributors of Sunbury Co-Operative Creamery butter. "In the face of this intense competition [from the margarine companies], it may be easier to understand the appeal of the sculpted butter cows," Simpson writes. "They offered proof of the glory and abundance of real butter made from real cows on real farms, not the fake white stuff manufactured by chemists. Moreover, the allusions that such butter cows evoke include a whole range of romantic assumptions about the cow, the farm, freshness, and innocence." Thanks to his support of the Pure Food And Drug Act Of 1906, Theodore Roosevelt was also a popular subject of butter sculpture, often depicted with lions.

Not everyone was impressed. At the St. Louis World's Fair, Minnesota History magazine reported, as various states vied to outdo each other with bigger and bigger butter sculptures (Missouri's contribution weighed in at 3,000 pounds), one visitor grumbled, "Butter is butter. Graceful and ethereal as its forms may be, one would not hesitate long to slice off a nose or a finger to butter his pancakes."

The most famous butter cow, the one at the Iowa State Fair, made its debut in 1911, sculpted by none other than John K. Daniels, creator of that butter version of the Minnesota state capitol. (Fun fact: Daniels lived to be 103.) The tradition has continued into the 21st century, largely thanks to Norma "Duff" Lyon, who sculpted the cow from 1957 until her retirement in 2006 (she died in 2011). When Barack Obama asked for her endorsement during his presidential primary campaign in Iowa in 2007, she gave it in the form of a 23-pound butter bust.

It is extremely tempting to imagine a butter sculptor like a dairy Michelangelo, hacking away at an enormous slab of butter to reveal the perfect hidden cow inside. (Of course, someone has already made a butter David.) But butter, even refrigerated butter, is too soft for that. Butter sculptors work like clay sculptors: they heap the sculpting material onto a wooden or wire armature, and then they mold the details. It's less wasteful, plus if the sculpture starts to melt—with cows, ears are especially vulnerable—it's easier to patch the whole thing back together. Simpson tells the story of an unfortunate sculptor at the 1906 Utah State Fair who spent five days carving a 40-inch tall dairymaid out of a solid block, only to hear that someone had left the door to the refrigerated compartment open and the woman's head had begun to melt into her chest. He was able to rebuild the neck, but he needed so much butter to do it, he said, that she looked like she had a goiter.

Sarah Pratt, Lyon's former apprentice, is the current sculptor of the Iowa butter cow (see her work of a buttered Kevin Costner at the top of this story). She works from a detailed photo, she told journalist Elaine Khosrova, who spent a week with her in her 42-degree studio for her book Butter: A Rich History. Pratt prefers Jersey cows for their expressive eyes. At the end of every fair season, Pratt usually asks her family to scrape the 600 pounds of butter off the armature and deposit it in buckets for her; doing it herself, she says, is too depressing. Sculpting butter can last for between five and 10 years. Even though she uses salted butter because it doesn't go bad as quickly, Khosrova reports that it still smells rancid. But, hey, it's an improvement: In earlier days, used sculpture butter was used as animal feed or, even worse, washed and repasteurized for human consumption.

The art of butter sculpture hasn't changed much in the 150 years since Caroline Brooks carved out her first bas-reliefs. No one may remember the original Dreaming Iolanthe anymore, but contemporary butter sculptors continue to depict important historical scenes like the moon landing and pop-culture icons from Elvis and Marilyn Monroe to Jabba the Hutt and John Stamos.

Dear @JohnStamos, I hope you like the @ButterStamos butter sculpture we made of you at #RiotFest. pic.twitter.com/YxdVKUySTe

— Riot Fest (@RiotFest) September 15, 2013

Scrolling through pictures of butter sculptures on the internet (which is something Caroline Brooks could never have imagined, though she would have had a great Instagram feed) is incredibly weird, but delightfully so. There are so many other, more far-reaching ways to advertise butter now, and the margarine demon has been pretty well vanquished, but there's still something irresistible and endearing about butter sculpture. It's an utterly benign form of American weirdness. And it reminds you that even something as utilitarian as butter can, in the right hands, with a little imagination, become something marvelous.