The Best Way To Preserve Your Family Recipes

Learn tips and techniques from people who have been making them the longest.

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Maybe you've been in a restaurant and spotted a dish on the menu that was always on your family's holiday table. Awash in nostalgia, you eagerly ordered it, only to be disappointed when it tasted nothing like the way your grandmother made it. Liz Williams has a tip for you: Take lessons from your elders, while you still can.

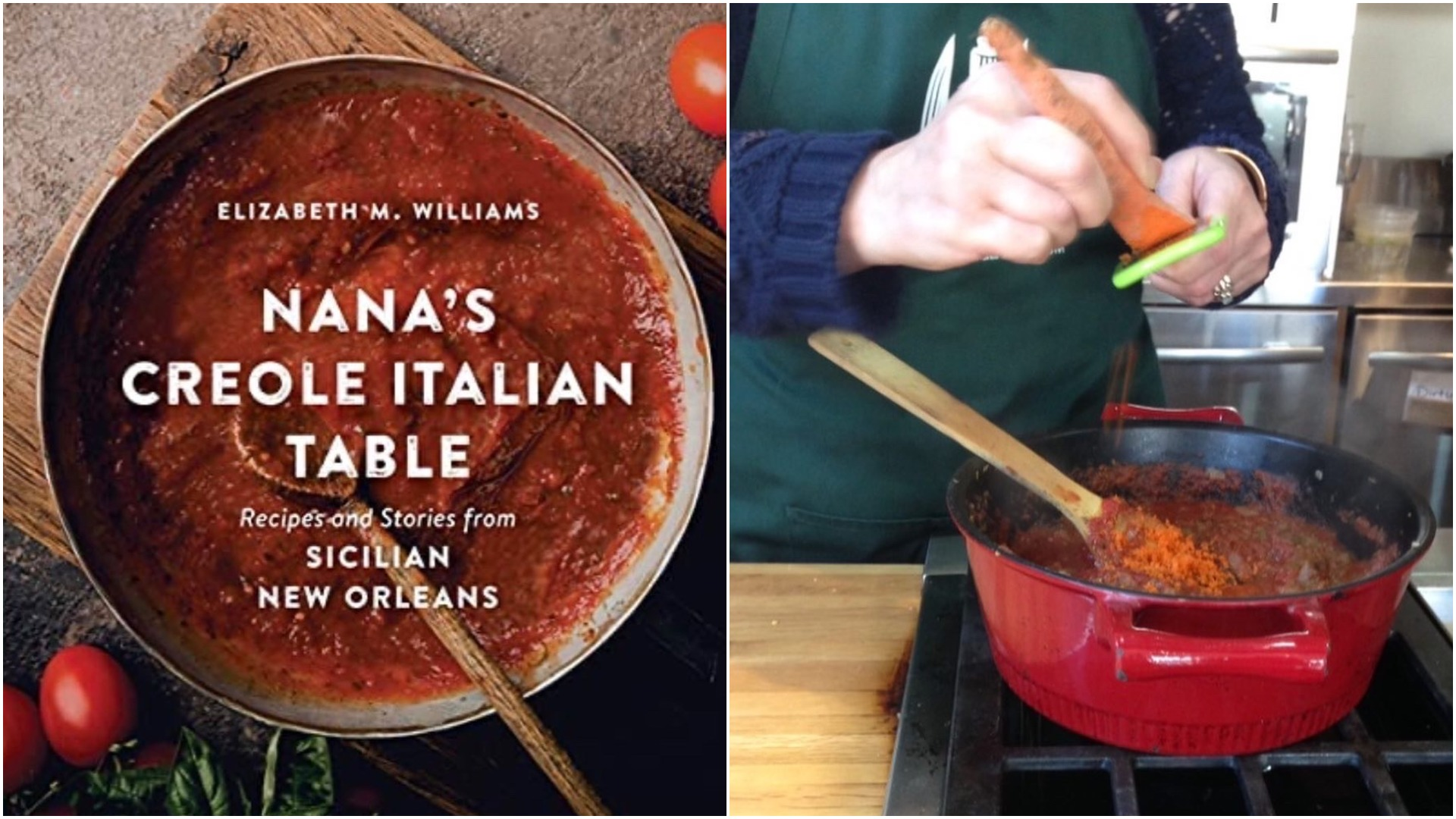

Williams is the author of the new cookbook, Nana's Creole Italian Table: Recipes and Stories from Sicilian New Orleans. Despite her Anglo-sounding name, Williams is descended from Sicilians who flocked to the Crescent City in droves during the late 1800s and early 1900s, attracted by plentiful jobs in the fruit and sugarcane industries.

Once they arrived, the newcomers began adapting the recipes they'd made in their homeland to the ingredients and customs they found on the Gulf coast. Today, examples of their cuisine can be found all over New Orleans, especially in restaurants that specialize in dishes served with "red gravy," the thick Sicilian version of tomato sauce.

You can find it as a pasta sauce, as a topping on meatball po'boys, and on New Orleans' version of Chicken Parmesan. I learned how to make red gravy a few years ago in a class that Williams taught at the Southern Food and Beverage Museum, which she founded. Like her tutorials, Williams' new cookbook offers stories and instructions on how to replicate the recipes she grew up with, and she offers advice for anyone who wants to capture their family recipes.

Cook with your elders

At a presentation sponsored by Gambit, the local news magazine, William shared her number one tip: "Cook with the oldest member of your family," she says. "Once they're gone, it's too late."

Seek out "the person who is closest to the place they came from," Williams says. If that isn't possible, find someone who learned from that ancestor. For instance, I never met my grandmother, who came to the United States from Riga, Latvia via Canada. So, my main frame of reference for family recipes was my mother rather than an earlier generation.

Don't just sit aside and watch them at the stove, either—instead, jump in and participate. "You're actually doing it together, and you learn all of (their) techniques," Williams says. As you're going along, write down the steps or record them on a voice app or video, if your elder is comfortable being filmed. You might want to hold more than one cooking session, so you get the experience of making the dish, and then can spend time documenting the dish.

Prepare for spontaneity in the kitchen

People who are used to following precise recipes might be surprised to find out that their elders do not cook that way, especially if they learned from earlier generations. While writing her cookbook, Williams realized that many of the books she admired were written by bakers, whose work is more like chemistry than improvisation.

Rather than a precise mise en place, Williams' ancestors had a broader viewpoint: use whatever was in the fridge that might enhance the dish. "Nothing went to waste," she said.

Her grandmother, she said, slit open a paper bag and set it on her cutting board before chopping vegetables such as broccoli, cauliflower, or greens. Then, she dumped all of the pieces, even the tiniest florets, into her dish. The flavor and texture of the dish often varied, depending on which ingredients were in season and the proportions that were used.

"Few members of my family made a Creole Italian dish in the same way," Williams writes in her book.

In other parts of the country, stuffed vegetables like peppers and tomatoes are often prepared with rice. But in New Orleans, the tradition became to use bread crumbs, from the French bread that's ubiquitous around the city, often as the carbohydrate conveyor for po'boys as well as a tool for sopping up every bit of gumbo. "Nobody wanted to throw away any bread," Williams explains.

Williams says she strove to write a cookbook that could accommodate that kind of ingenuity rather than make readers follow a stringent set of orders. "It's not a rigid blueprint for something, and I think most people who like to cook pretty much do that," she says.

Measuring your measurements

While the two of them were cooking, Williams often watched her grandmother measure ingredients with a broken teacup with a missing handle. While she called it a cup, it was not precisely the standard measurement of eight ounces. "If you ever sat with her, you had to know that it was that teacup," Williams says. "It was not three standard cups."

If your elder does something similarly idiosyncratic, Williams suggests measuring the conveyance's volume, then translating it into standard measurements. It's best to do this subtly, though. Try not to imply that they've been doing anything unusual or incorrect, because cooking can be very personal, especially when someone has been making a dish one particular way their whole lives.

That's especially important if English is your elder's second language. They may have been bewildered by American cooking techniques and see their own as not only a comfort, but a skill that gives them confidence. "When my grandmother served her family something familiar, she not only nourished, but she mitigated the longing for home and difficulties of adjusting to a new culture and language," Williams writes.

Find recipe variations that honor the original

New Orleans is better known for its French and even Spanish heritage than it is for the role played by Sicilians. Along with red gravy, there's another visible legacy brought by these immigrants: olive salad. It's a key feature on a muffuletta, the big, hearty sandwich with cold cuts and cheese available at places like the Central Grocery.

Olive salad is a roughly chopped mix of green and black olives, capers, pickled vegetables, onion, vinegar, oil, and spices. But Williams says it wasn't part of New Orleans cuisine until the Sicilians came. "The French and Spanish brought us olives, but they didn't mix green and black," she says. The new arrivals made use of broken olives that grocers otherwise processed into tapenade.

Williams' book has three versions of olive salad: her grandmother's, which is close to the salty, garlicky olive salad sold in corner stores; her mother's, which includes an entire lemon, peel and all; and her own, which introduces basil, artichokes, and fennel to the mix.

Talking with your elder, you might find another such dish which their culture takes pride in introducing to Americans. If so, that could be a good starting point for your culinary conversation and cooking lessons.

Three Generation Olive Salad recipe

From Nana's Creole Italian Table: Recipes and Stories from Sicilian New Orleans by Elizabeth M. Williams

- 1 anchovy filet

- 1 1/2 cups fruity olive oil

- 10 boiled and quartered baby artichokes (fresh or frozen, see tips below)

- 2 cups coarsely chopped green olives with pimiento

- 2 cups coarsely chopped pitted black olives

- 1 cup finely sliced celery

- 1 cup finely sliced raw carrot

- 1 cup finely chopped raw cauliflower (optional)

- 1 very very thinly sliced lemon, including the peel (remove seeds)

- 1 bulb raw fennel, thinly sliced

- 4 garlic cloves, minced

- 6 Tbsp. chopped fresh oregano, or 4 tsp. dried

- 1/4 cup coarsely chopped capers

- freshly ground pepper to taste

- salt (optional)

- 1 cup fresh basil leaves (optional)

- The better quality olives, the better it will taste. Try to purchase bulk olives rather than canned ones.

- Williams advises cooks to avoid canned artichokes, which will alter the texture of the salad. She prefers fresh ones. If using frozen, boil and cool them before chopping.

- Serve on a sandwich, or pile on salad greens. It also can be used to stuff tomatoes, or layered with tomato slices as a side dish.

In a large bowl, combine the anchovy with one tablespoon of olive oil until the anchovy dissolves (add a little more olive oil as needed). Combine all the ingredients except the remaining olive oil.

Add enough olive oil to cover the mixture. Stir well so the ingredients are evenly distributed. Let it sit an hour, then taste. If it needs acidity, add a little lemon juice. Because of the olives and anchovy, it probably will not need additional salt, but add it if you like. Add the optional basil leaves at the end, before serving. The recipe makes about two quarts.

Tips: