Classic Cookbooks: The Art Of Cookery Made Plain And Easy By Hannah Glasse

I wish I could tell the story of Hannah Glasse as a movie. It would have two parallel timelines, like Julie & Julia. We would begin in 1937, in a picturesquely dusty library somewhere in Northumberland, England, where Miss Madeleine Hope Dodds, known to the general public as M.H. Dodds, sits shivering and perhaps also sneezing as she pores over old letters, newspapers, and parish records. For this is the singularly unglamorous life of a historian.

Miss Dodds is 52 years old. She has a friendly smile and wears her long hair braided and coiled neatly on top of her head. Let's also give her a pair of reading glasses. Her specialty is the history of northern England. Twenty years ago, she and her sister Ruth had published The Pilgrimage of Grace, 1536–1537, and the Exeter Conspiracy, 1538, a well-regarded history of two uprisings against Henry VIII. At the moment, she is engaged in creating a pedigree of the Allgood family, which lived in and around Hexham in the 17th century. There have been moments of interest—the mother of one woman who married into the family was executed as a witch—but the Allgoods in general were respectable rectors and solicitors.

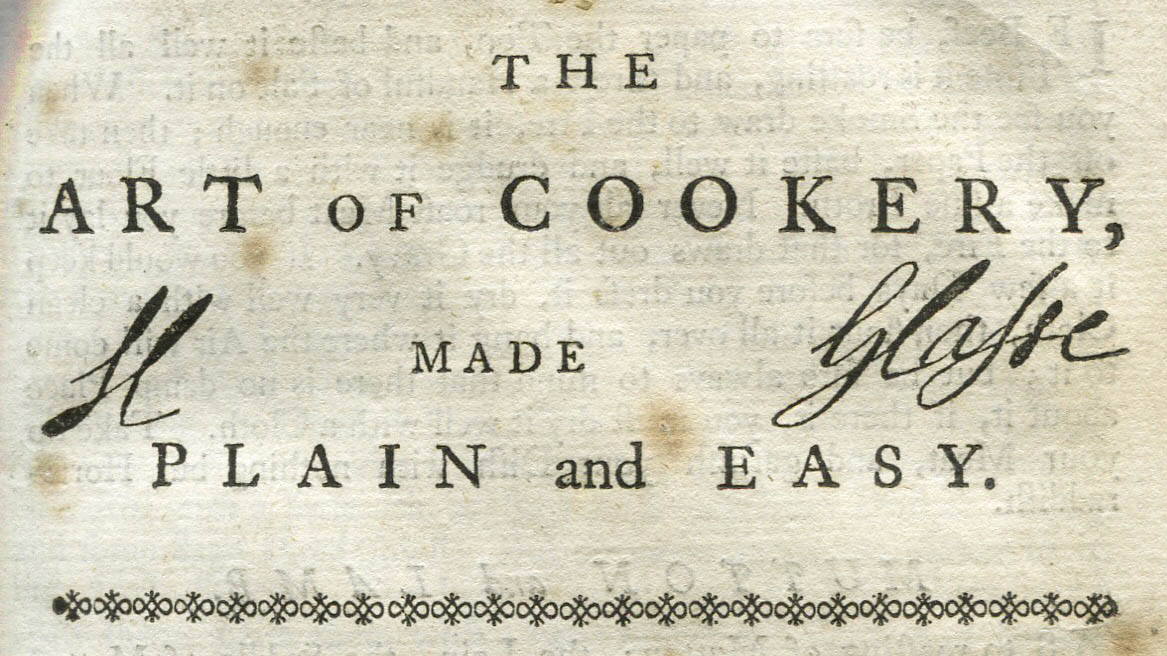

Miss Dodds has taken an interest in the Allgoods because the names of several of them appear on the subscription list for a slim 1747 cookbook called The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy; Which far Exceeds any Thing of the Kind ever yet published. In the 18th century, it was common for publishers to get readers to "subscribe to"—that is, pay for—books before they were published; then their names would appear in the book itself. The 1747 edition of The Art of Cookery is credited to A Lady, although later editions bear the name of Hannah Glasse. Who was Hannah Glasse? An advertisement in the fourth edition identifies her as "Habit Maker to Her Royal Highness the Princess of Wales" and notes that she lives in Tavistock Street in London near Covent Garden. Miss Dodds has consulted The Dictionary of National Biographer, which contains only a discussion of whether Hannah Glasse was indeed the first person to issue the cooking instruction "First catch your hare" and the suggestion that the cookbook author may be the same person as a "Hannah Glass" who declared bankruptcy in London in 1754.

But here! In the will of Isaac Allgood, who died in 1725, there is a mention of his daughter, Hannah Glasse. "Eureka!" cries Miss Dodds.

And now, in a quick cut, we come upon an entirely different scene, in a brighter and more exciting color palate: London, 1724. Hannah Allgood, the daughter of Isaac Allgood, a prosperous coal mine owner, and his mistress, Hannah Reynolds, is living with her grandmother. The two Hannahs had been brought to Northumberland to live with Allgood's wife, also named Hannah, and his other children, but things had turned sour between Isaac and Hannah Reynolds, and she had taken their daughter and decamped for London. The two Hannahs did not get along, either—the younger Hannah would describe her mother as "a wicked wretch!"—which is why young Hannah is living with her grandmother. Her grandmother is strict, but Hannah, age 17, has met a dashing 30-year-old Irish subaltern named John Glasse. (Or maybe it was Peter?, Miss Dodds wonders. In the records, his name keeps changing.) Let's begin with their elopement, a dramatic and romantic scene with teenage Hannah climbing out a window, descending a trellis of ivy (or something like that) and falling into the arms of her lover.

Ah, love! The Allgoods are not pleased with the elopement at first, but Isaac dies the next year and leaves Hannah some money. Children appear regularly; there will be 10 in all, though only five will live to adulthood. Cue a montage of domestic tranquility: a nice—but not grand—house in London where Hannah, clad in an apron and a mob cap, consults with the cook—a stout woman with gray hair and a salty disposition who does not suffer fools gracefully—while children run in and out, and John/Peter comes home and sweeps his wife up in his arms.

But then the money runs out. Or times get hard. Either way, the Glasses are out of funds. At first Hannah tries selling a patent medicine called Daffy's Elixir, but things do not go well. (Imagine crates of unsold bottles piling up in the Glasse kitchen.) But then Hannah has her a-ha! moment, perhaps in the middle of some especially horrible bit of domestic chaos. Her spirit is nearly broken, but then she rallies. "I shall write a cookbook!" she declares.

Hannah scribbles away with her quill by candlelight. We hear in voiceover, "First, case your hare." (Thus solving another old mystery: "case" means "skin," so Hannah Glasse was not the badass hare-catching outdoorswoman later writers have given her credit for being.) She consults with her salty cook once more—let's give them an Odd Couple sort of relationship, in which animosity melts into mutual respect and even a sisterly bond. She leafs frantically through existing cookbooks. She peers at a ticking watch and measures the heat of the oven with her hand. There is at least one catastrophe involving an overflowing pot and another with a too-hot fire. The children bring in piles of firewood for the stove and grumble as they are forced to eat their mother's experiments. But after several years (maybe five minutes in movie time), Hannah triumphantly presents her publisher with a full manuscript. Cue a shot of a printer working frantically, setting type and running the press. And then we see it, the first page!

It's time for another montage. This time we see housewives in the kitchen with The Art of Cookery propped up against enamel jugs and copper bowls, awestruck by the book's innovations. We see them whipping egg whites so that their cakes will rise (previously, bakers had used yeast). We see them pulling trays of Yorkshire puddings out of the oven, pouring creamy Welsh rarebit over toast, roasting enormous cuts of meat and covering them with savory sauces, simmering soups, reducing stock to a shelf-stable bouillon-like "pocket soop," and presenting an old soldier who has spent his career in India with the first real curry he's had since his return to England. (He wipes a tear from his eye.) There is also a comic recurring bit with one young kitchen maid trying to skin a calf's head.

Cut back to 1937. Miss Dodds stands behind a lectern reading the paper she has written recounting the history of Hannah Glasse to the all-male members of a historical society. One of the men, an odious-looking fellow, stands and adjusts his spectacles. "Pardon me, Miss Dodds," he says, "but are you aware that Hannah Glasse was a fraud and a plagiarist?" And here he brandishes a volume called The Essay upon the Lady's Art of Cookery by a woman by Ann Cook, who was so consumed with hatred for the author of The Art of Cookery that she could only express it in poetry, which the male historian quotes with evident satisfaction:

If genealogy was understoodIt's all a Farce, her Title is not good;Can Seed of Noble Blood or renown'd SquiresTeach Drudges to clean Spits and build up Fires?

He also happens to have brought extracts of recipes from other leading (male) cookbook authors of the day that are strikingly similar to those in The Art of Cookery, down to names, ingredients, and preparations.

Poor Miss Dodds! What an ambush! Her face is frozen in horror. A lone woman in the back of the room frowns, but Miss Dodds is too caught up in her humiliation to notice. Later, in the comforting arms of her sisters, she sobs. But she will not be daunted! Back to the library she goes—no, not to the library, to a warm, cozy country house well-stocked with antique cookbooks. It all belongs to the woman at the historical society, who happens to be a wealthy dowager countess and an avid cookbook collector. The conscientious staff has been instructed to keep Miss Dodds amply supplied with tea and any other refreshments her heart desires. God knows she needs them.

(These scenes never happened. The real Madeleine Dodds was well aware of Ann Cook, and her paper about Hannah Glasse includes a long section about the source of Cook's animosity.)

Cut back to 1747. We meet Ann Cook, a professional cook, wife of an innkeeper in Northumberland, and aspiring cookbook author, who reads The Art of Cookery with fierce professional envy. Then she comes to the list of subscribers in the back. Her beady eyes light on the name Allgood. We flash back to a scene in which Lancelot Allgood, Hannah Glasse's brother who'd had the good fortune to marry an heiress, accuses Mr. Cook of fraud before a magistrate. Ann Cook sits in the back of the courtroom, her face compressed with rage. Revenge shall be hers!

Meanwhile, Hannah Glasse, unsuspecting, is the toast of London. Had the Food Network existed back then, she would have had her own show. But instead, she must be content with seeing her words quoted in the papers, hearing whispers of "Mrs. Glasse says," and a sweet, sweet gig as seamstress to the Princess of Wales. And then one day, her own salty cook, wearing a grave expression, shows her a volume called Professed Cookery: containing boiling, roasting, pastry, preserving, potting, pickling, made-wines, gellies, and part of confectionaries. The author is none other than Ann Cook. Hannah pages through it and sees the essay/poem about how she is a fraud. Her face goes white. The newspapers have a field day. The Princess of Wales sends her away. The next thing we know, Hannah stands before the magistrate and tearily admits that she cannot pay the £10,000 she owes her creditors. He sentences her to debtors' prison. She grasps the bars of her cell and looks distraught.

(In real life, bad business decisions, not Ann Cook, were the cause of Hannah Glasse's financial downfall. She really was £10,000 in debt, though.)

In 1937, Miss Dodds flips through old cookbooks with greater and greater excitement. She very nearly rips a page, much to her chagrin. The braid on top of her head begins to unravel and her spectacles slide down her nose. Cut to her study, where she bangs on a typewriter. Cut to the kitchen where she and her sisters cook Mrs. Glasse's recipes while a radio plays a jaunty popular tune of the day. Someone flips a pancake.

Hannah Glasse is free from prison after six long, lonely months. It is December. The snow is blowing. Her oldest daughter, accompanied by the salty cook, escorts her from the prison and takes her to a confectioner for a dish of ice cream because Hannah has always told her that sweets make everything better. Hannah takes a spoonful of raspberry-and-cream ice, and a smile crosses her face. Cut to Hannah back in the kitchen with the salty cook, churning up buckets of sweet ices for a brand new book about confectionary.

It's about time for Miss Dodds' happy ending as well. She stands before the historical society once more, and in her best Perry Mason style lays out the source of Ann Cook's vendetta against Lancelot Allgood and, by extension, Hannah Glasse. And then she brings up the recipes. Yes, Hannah Glasse copied some of her recipes, Dodds admits, but take a look. Where the earlier cookbook writers used ridiculously formal language and operated under the assumption that the reader would merely pass instructions onto her cook, Hannah Glasse was writing for the middle-class woman who actually spent time in the kitchen. Recall that the title of her book was The Art of Cookery made Plain and Easy: Hannah Glasse took those older recipes and made them plain and easy to understand and use. She rearranged the steps so they proceeded in a logical order. She included temperatures and cooking times down to the minute, which no one had thought to do before. All this, and she gave us curry and Welsh rarebit and Yorkshire pudding, too! Your honor, the case rests. "Oh, I beg your pardon, gentlemen," Miss Dodds laughs, "I got a bit carried away."

(In reality, it was the culinary historian Jennifer Stead who made the case for Hannah Glasse as an innovator who improved upon the recipes she stole. Stead also points out that recipe theft was pretty common in the 18th century, when plagiarism laws were much less harsh than they are now. Anne Willan and Kate Colquhoun in their respective books Women in the Kitchen: Twelve Essential Cookbook Writers Who Defined the Way We Eat from 1661 to Today and Taste: The Story of Britain Through Its Cooking describe Glasse's innovations in much greater detail.)

The men of the historical society break into applause and then, one by one, clamber to their feet. "Huzzah to Miss Dodds!" they cheer. "And to Hannah Glasse, the inventor of modern cookery as we know it!"