6 Craft Beers For June That Anheuser-Busch Hasn't Bought Yet

While the rest of the world obsessed over Comey, Russia, and massive document dumps in May, the craft beer world followed its own completely separate soap opera. First, on May 3, Anheuser-Busch InBev bought Asheville, North Carolina's Wicked Weed Brewery, a highly regarded regional brewery known for sour beers. The next day, Lagunitas—already half-owned by Heineken—sold the other half of its business to the Dutch mega-brewer. The rest of the month, craft beer purists worked to outdo each other in displaying their contempt for AB InBev: Brewers pulled out of Wicked Weed's annual sour beer festival (leading to the event's postponement and reconfiguring), hops suppliers cried foul when AB InBev kept the entire South African hop harvest for themselves (and the 10 craft breweries they've purchased) and a guy in San Diego decided to rain on the grand opening of a new 10 Barrel Brewing Company brewpub by pointing out the company is actually owned by AB InBev—an aerial banner reading "10 BARREL IS NOT CRAFT BEER" flying over their block party was his medium of choice. He asked for $900 on GoFundMe, and raised almost $5,000.

By contrast, the most serious response to the Lagunitas sale was some major eye-rolling at founder Tony Magee's over-the-top blog post (where he compared himself to Jonah being eaten by the whale).

This past month of beer news was like a Rorschach test for beer lovers—reactions were strong and served to sort folks into oppositional camps. There was even a beer blog that published a blacklist of breweries and other beer blogs owned or funded by AB InBev called "The Cut Off." That list made no mention of Lagunitas or any other breweries recently purchased by companies other than AB InBev like Ballast Point, Firestone Walker, or Cigar City. For a certain segment of beer enthusiasts, animosity toward Anheuser-Busch is at an all-time high.

Perhaps we're seeing the seeds Samuel Adams founder Jim Koch planted in his April op-ed in The New York Times begin to sprout. Under the provocative headline, "Is It Last Call For Craft Beer?" he laid out a case the case that AB InBev's anti-competitive practices could spell the end of craft beer as we know it. His argument centered on its merger with SABMiller and unfair distribution practices. Though derided by some at the time as a way for Koch to justify Sam Adams' sagging sales figures, the past two months have probably caused some of Koch's critics to change their tune.

No matter how AB InBev makes you feel about your beer, chances are there's something you would like in this month's Pick Six. I can, however, guarantee you that AB InBev owns zero percent of these breweries as of June 1, 2017.

Boulevard Brewing Co. (Kansas City, Missouri) American Kolsch

The label calls this a "Köln-Style Golden Ale" below a drawing of a dude in a hammock. That image is perfect for this refreshing, crisp beer. Kolsch is an ale that could pass a taste test as a lager: It's that clean and bready, but with a few more layers of flavor. So if you're interested in beer that would taste like "beer" to Don Draper but don't want to jump on the craft pilsner train, kolsch is for you. As of January this is a year-round brew for Boulevard, which was purchased by Belgian brewery Duvel Moortgat in 2013.

Rogue Ales (Newport, Oregon) Honey Kolsch

Another variation of refreshing beer for the first days of warm weather, Rogue adds a subtle touch of terroir by adding Rogue Farms Hopyard Honey to the mix. Where Boulevard's offering is bright, this beer adds a hint of earthiness and offers additional layers of a flavor to consider. A very restrained effort for the brewery that makes Hot Sriracha Stout.

5 Rabbit Cervecería (Bedford Park, Illinois) Paletas Guava Fruit Beer

This summer refresher makes no bones about it: It is a pink beer that tastes like fruit, but with a complex profile that's not sweet, and is even a little bitter. Only a clueless victim of toxic masculinity would call this a lady's drink, but if pink makes you uncomfortable, this highlight of the season now comes in opaque cans. You can hang out pumping iron and checking out hot rods and no one will know you're drinking a pink beer. Me, I'll be drinking this out of a glass, waving it like a pink flag.

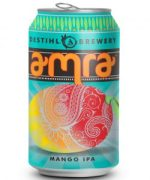

Destihl Brewery (Bloomington, Illinois) Amra Mango IPA

This beer's name is redundant if you are fluent in Sanskrit: Amra means mango. Mango IPA is just about all you need to know about this juicy, sweet nectar of an IPA. Designed as a gateway for hop skeptics, there is no bitter wallop to watch out for here. However, there also is no cloying sweetness from unfermented fruit juice. Instead the hops and mango intertwine with the malt backbone to create a deeply satisfying experience. The brewery sent this beer to me, probably hoping I'd mention its new $14 million dollar facility that opened this weekend in downstate Illinois, and now I have.

Crazy Mountain Brewing Company (Edwards, Colorado) Lawyers, Guns & Money Barleywine Style Ale

If there's any beer that's appropriate for our current administration, it's this one named for the Warren Zevon song about going home with a waitress who was "with the Russians, too." Even if you're not Sean Spicer or Jared Kushner, the 10 percent ABV will help any as-yet-untold bombshells go down just that much easier this month. Plus, though labeled a barleywine, the dry hopping makes this almost an Imperial IPA, so drinking it outside on a sunny day isn't entirely inappropriate.

Middle Brow Beer Company (Chicago) The Milk-Eyed Mender Imperial Milk Stout

Another beer named for after music (the debut album by Joanna Newsom), I had my first sample of this at a beer dodgeball event two years ago. I'd given up on finding this milk stout with three kinds of peppers, cacao, vanilla, cinnamon, and sweet orange peel in a bottle. But low and behold, at the Whole Foods next to the Fullerton Red Line station, on the second floor, tucked between six packs was the weird two-pack this beer is sold in. I bought it immediately despite its 10.3 percent ABV and the imminent arrival of summer. I plan to have it ready for the first summer evening I sit late into the night on my deck with friends and need a perfect nightcap. My compatriots won't believe how well the peppers come through with almost no heat at all, creating a complex flavor tapestry that continues to unfold with each successive sip. "Warp woof wimble" indeed, Joanna.

If you have a brew you'd like considered for Pick Six, send us an email at avclubbeer@gmail.com.