Slang Jang Was A Family Recipe I Thought I Hallucinated

While American cuisine has quite a few universally agreed-upon summer staples—hamburgers and hot dogs, ice cream and apple pie, grilled anything—some of the more adventurous foods of the season can be found in the passed-down recipes of family get-togethers. These are the dishes that come with long-winded stories boisterously told at maximum volume over the sound of sizzling meats, backyard festivities, clinking bottles, and your uncle's "don't touch my stuff" playlist of not-so-expertly curated jams.

Inherent in most of these left-of-center dishes is some nostalgic mixture of now and then, blending the fabled recipe's origin story with the continually evolving tale of how it was "improved upon" over the years by members of the family. Whether the concoction has been meticulously transcribed onto a recipe card or protectively locked away in the minds of those that prepared it, there's an integral piece of the puzzle required to facilitate the hand-me-down process and ensure the recipe's continued survival.

You've got to know the name of the dish.

If you don't, you might embark on a two-decade journey of fruitless internet research that will have you questioning your own reality of false memories. Hypothetically speaking, of course.

When I was a kid, one of my most anticipated summer activities was getting together with my dad's side of the family so they could make a huge pot of the most deliciously pungent seafood soup my pre-teen palate had ever tasted. The base was made from tomatoes and dill pickles (brine included), onions mixed in for texture, plus hot sauce. Then it was packed to the brim with shrimp, oysters, crawfish, clams, and any other seafood they could get their hands on. The ingredient list was varied and often open to improvisation (they hit the '80s craze of Asian-inspired flavors pretty hard for a few years by adding in bean sprouts, bamboo shoots, and water chestnuts). However, the preparation was rigidly simplistic: Chop everything up, mix it all together in the biggest container on hand, and chill it in the fridge for a couple hours—or as long as it takes to get through an 8-person round of Spoons. Salt and pepper to taste.

The refreshingly cold summer soup was called "Slain Jane," or so I thought, and I never questioned the seemingly morbid etymology of the name. In fact, in my over-imaginative, horror-movie-loving kid's brain, that name made perfect sense for the aesthetics of the dish. The watery, red base from the tomatoes and the pale, fleshy chunks of seafood meat were quite evocative and I immediately retrofitted a Southern-gothic backstory to its creation. It was a murder ballad in food form—no further questions, your honor.

This dish was a summer mainstay until I was in my late teens, but within the span of a few years my dad passed away, I got married, and we relocated to Tennessee. The dish turned from a meal to a memory and as I feebly tried to explain it to new friends at summer barbecues, I sounded like a raving madman making a dish up on the fly: "Seriously, cold pickles and hot sauce taste amazing together. You can just eat around the tomato chunks and water chestnuts if you want. Plus, the vinegar, clam juice, and pickle brine marinate the seafood in a way that makes each bite pop with this cold flavorful tang you can't get anywhere else." Words weren't enough to sway the inhabitants of a pre-Yelp world, so I knew I'd eventually have to make it myself to win anyone over with its refreshing, oddball deliciousness.

My interests in whipping up my own batch of "Slain Jane" was immediately thwarted by failed internet searches for the recipe. I Yahooed, AltaVistaed, Dogpiled, Asked Jeeves, Binged, and Googled—all with zero success. I tried searching for "Slain Jane" and variations of cold tomato soups and got nowhere. I could get somewhat close—seafood soups without the pickles, tomato-and-onion dishes that drained out all the liquids, various salsas and gazpachos—but they were all missing a key component or two. When I would search for just the words "Slain Jane" I couldn't even get help with Google's automated recommendations. Did you mean: plain jane? Here are 3,175,000 results for that.

This went on for years, almost two decades actually, and the whole process made me start believing in The Mandela Effect: the psychological phenomenon that involves having a vivid memory of something that never actually occurred. While it's true that one component of the Mandela Effect is that the false memory is shared by multiple people (you technically couldn't have an individualized Mandela Effect) I figured that my family constituted enough of a sample size to count. We all had memories of the dish as a yearly summer tradition, no matter what Google search results turned up.

But then, earlier this year, something must have finally changed in Google's search algorithm.

Did you mean: slang jang?

I curiously clicked the link and I swear I heard Handel's "Messiah" cue up softly in the distance. I was soon basking in the glow of 1,060,000 results for Slang Jang, a tomato-based dish of mixed vegetables and liquids that is almost exclusively associated with the Texas town of Honey Grove. Even before diving into the specifics of the dish, I knew I was on the right track because my dad's family was from Paris, Texas, a town 20 miles from Honey Grove on the northeastern corner of the state. As I started clicking on the various links and reading about the regionalism of Slang Jang, I was struck by the folksiness of its origins and the free-form nature of assemblage.

Much like the dish itself, the story of the invention of Slang Jang features a few definitive elements anchoring an evolving cast of peripheral components. According to the Honey Grove Preservation League site, Slang Jang was created around 1888 by a group of men who quickly threw together lunch one day by going through a grocery store and dumping cans of food they liked into a giant washtub. By 1895, Slang Jang had received its first mention in the Honey Grove Signal newspaper: "Saturday night the Masonic bretheron to the number of about forty-five gathered at the parlor of W. H. Hill & Co., and partook of a bounteous repast consisting of 'slang-jang' and other favorite dishes." Slang Jang became such an integral piece of Honey Grove lore that when the first Honey Grove High School yearbook was produced in 1914, it was called "The Slang Jang" and included the following description in its introduction:

Slang-Jang. n. A delectable mixture of liquids and solids which originated in the city of Honey Grove, Texas, about the year 1888. A dish that everybody likes and nobody can get enough of. Never known to make any person sick, no matter how much of it was consumed. It is claimed that this dish can only be compounded correctly in Honey Grove, or by a native of Honey Grove.

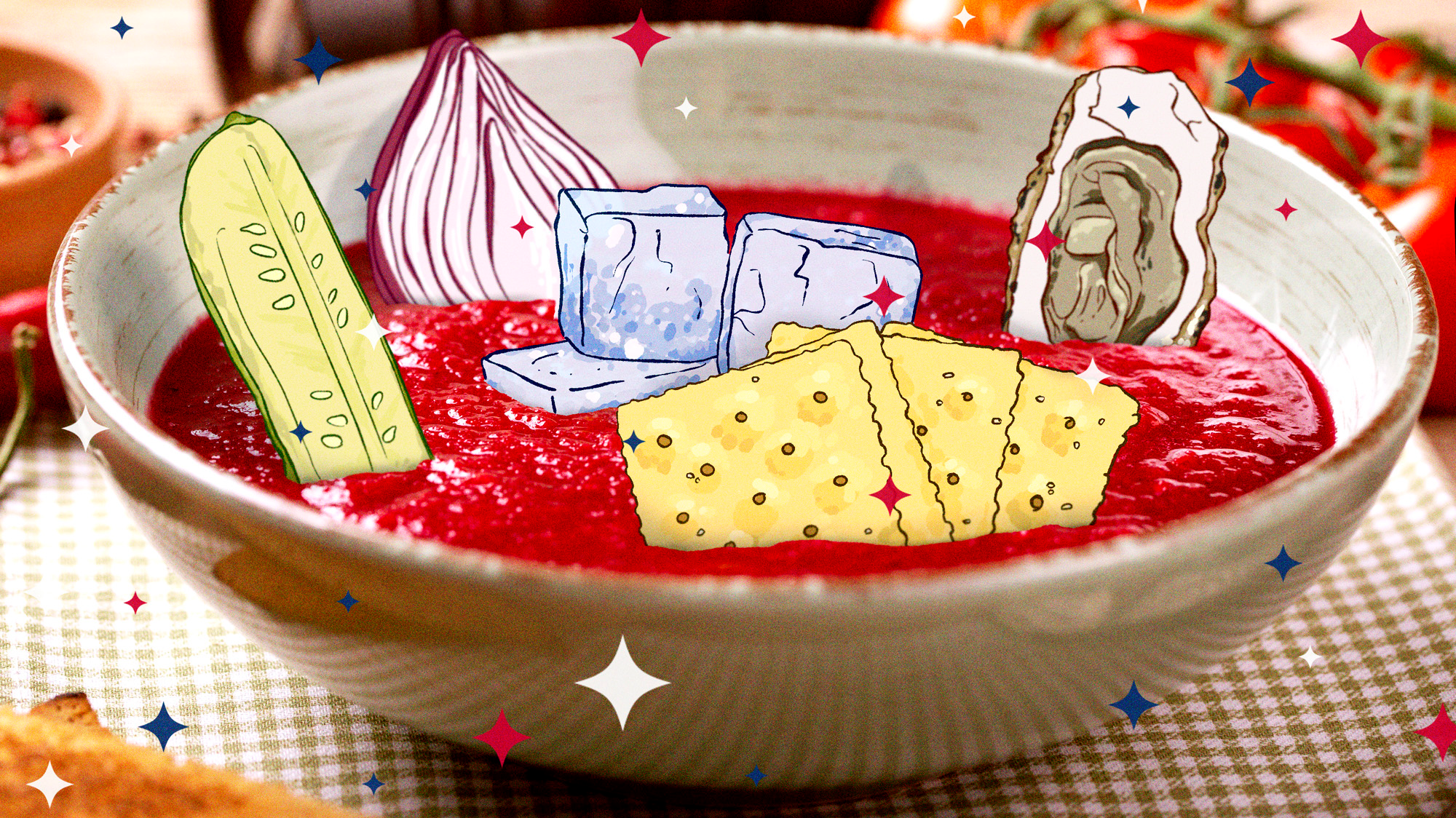

Reading further into the history of Slang Jang, it's unbelievable to see how many different variations there are on the dish. Depending who you ask or whose cookbook you're perusing, Slang Jang can be a seafood cocktail served with crackers and cheese, an oyster-heavy condiment meant to be served over black-eyed peas or fried okra, a salsa dip thickened with crushed-up crackers and ladled out into cups, or a standalone meal hearty enough to anchor decades of celebratory Slang Jang Supper gatherings.

A 1956 Honey Grove Signal article even stated that Slang Jang is "neither a soup nor a salad but a snack, a relish," going on to call it both a "weird concoction" and, my personal favorite descriptor, a "community project." Even as recently as last year, Coast Monthly magazine wrote about Slang Jang and even included a deliciously simplistic recipe reprinted from a 1932 church cookbook. It seems Slang Jang can take on about any form you can fathom, as long as it's anchored around its chilled primary components—tomatoes, pickles, onions, oysters, and ice.

Tomatoes, pickles, onions, oysters, and ice sound like a dastardly Chopped basket, but truly, it works together. Out of the fridge, the first thing that hits you is the aroma of pickle brine, hot sauce, and seafood. It's an unfamiliar-yet-welcoming dance between vinegar, spice, and salt water—like inhaling in a misty Pacific Northwest day with a Bloody Mary in hand. Once served, the chill coming off the bowl subliminally alerts your taste buds that something refreshing and invigorating is on its way.

As a kid, I always tried to make my first spoonful just the cold broth because then you can decide if the prep cooks hit the salt and heat right. (More often than not, I ended up adding more hot sauce). Once you have the liquids balanced out to your preference, there's nothing left to do but enjoy the explosive tastes of seafood that's been marinating in pickle brine, hot sauce, and clam juice for the last couple hours. The diced vegetables soak up the flavor (making the onions all the more palatable) and the substantial tomato base provides a background lightness without getting lost amongst the more boisterous ingredients.

In my early days of tumbling down the Slang Jang rabbit hole, I was honestly confused by how far my family had strayed from the original dish. Nothing I could find really matched the soup-like consistency that we were accustomed to and, apart from the oysters, no one seemed to include the variety of seafood that we did. (Not to mention, I couldn't find anyone who ventured anywhere close to our beloved, limited-edition Yan Can Cook variation).

However, as I continued my obsession with researching Slang Jang's tiny corner of the internet, I found myself appreciating both the rebellious nature of its adaptability and my family's willingness to celebrate its unruliness with whatever they felt like adding to it each year. Want to try spicing it up with some peppers? Sure thing. Vienna sausages this year, why not? Our soupy, seafood-heavy version may have looked a little different than the inaugural washtub batch of 1888, but it seems like maybe that's the most integral part of the dish's charm. I guess in doing it mostly wrong, we ended up doing it just right.