Salt Grinders Are Bullshit, And Other Lessons From Growing Up In The Spice Trade

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Editor's note: This story was first published in April 2017. We're republishing it today because its author, Caity PenzeyMoog, received a book deal from this story! On Spice: Advice, Wisdom, and History with a Grain of Saltiness will be released by Skyhorse Publishing on Jan. 15. Way to go, Caity!

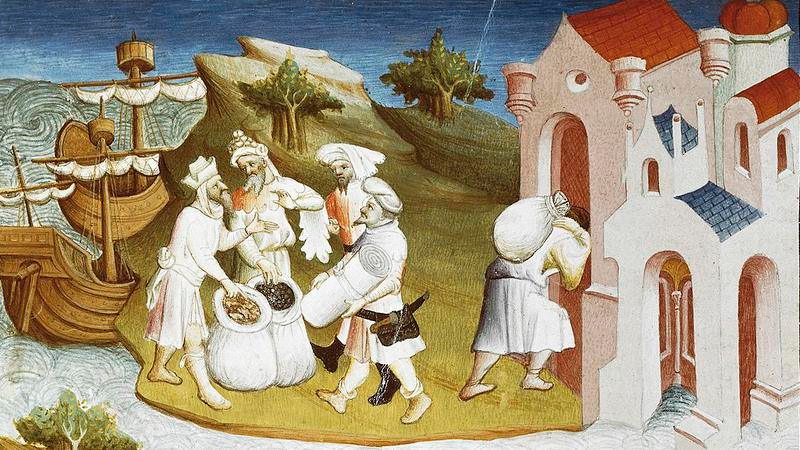

When I was a kid, I had no trouble describing what my dad did for a living. He was a chef (and still is). Harder to explain was what my mom did; there wasn't a word for her job. And so, with my child's head full of fantasy and what I read in books, I insisted my mother was a spice merchant. It gave a historical heft to her job in my family's spice business, calling to mind 15th-century traders on ships transporting dusty burlap sacks filled with exotic goods across seas.

And to some extent, that childhood romanticization of my family's trade wasn't far off. My grandparents' spice shop—where the family business started and where I spent many of my childhood summers and Christmas breaks—overflowed with colorful tins of saffron from Spain, enormous crates of salt the size of pebbles, burlap sacks bearing stamps from all over the world. India, Turkey, Ethiopia, Greece—products from every corner of the globe made their way to a small building in Wisconsin. Growing up in a family steeped in the spice business formed a child for whom blandness was a cardinal sin. Not much has changed since. I still heavily season most everything I eat (some might say over-season). And as my co-workers can attest, I have very strong opinions about food and flavoring. The way I speak on spices isn't so different from my fellow pop-culture-obsessed A.V. Club staffers, though: Just as our film editor butts into a conversation to defend the visuals of M. Night Shyamalan's Split, every time I see a salt grinder or hear someone bad-mouth MSG, I feel obligated to interject.

A lot of people are familiar with Penzeys Spices, but I spent my formative years at the Spice House, which my grandparents owned. Unlike Penzeys stores, which are orderly and tidy and bring to mind a spacious kitchen, the Spice House was cozily cramped and exuded an organized chaos. The hundreds of spice-filled apothecary jars lining the shelves tended to move around a lot, sometime disappearing altogether, reappearing days later. Overenthusiastic customers would set off cinnamon bombs in their eagerness to sample the difference between Vietnamese and Saigon cinnamon. We'd pour seasonings into little glass jars right there on the counter, where large metal bowls and tiny metal scoops would be abandoned when a rush of people came in. By the end of the day, the floor would be scattered with bay leaves.

That was just the front room that customers saw. The large back room bore witness to my grandparents' esoterica, jumbled onto yet more shelves, which overflowed with spices and their appurtenances, cookbooks and philosophical treatises, photos of Julia Child cooking with our spices next to photos of my siblings and me mixing seasonings as toddlers, art projects and paints, Hershey bars and mint gum, tiny boxes from China containing cloves, and sheaves of paper of extensive handwritten notes.

This is where my grandparents would call my brother, sister, and me back when the rush of customers slowed, to read Gurdjieff out loud or mix cinnamon sugar while reciting the poem "Desiderata." We'd do this while making a blend, which we'd stir in an enormous metal bowl exactly 111 times. My grandfather would make us pork chops on a George Foreman grill, seasoned with some unknowable pepper mix. The air was perpetually thick with the commingling of hundreds of spices, herbs, sugars, and salts, blending into a distinctive smell that lingered on your clothing and in your hair all day. It formed thick dust motes that floated in the sunlight coming through windows.

You'd think that spending a lot of time here would numb your olfactory senses, but the opposite was true. My nose learned to cut through the background smell to identify specific spices within the store—a good thing when replacing the apothecary jars with their correct lids, which is easily done when you can discern oregano from parsley and garlic from ginger.

Still, growing up in the family spice business was for me more about the "family" than the "business." It wasn't just learning to identify peppercorns by their size, but also listening to my grandfather read Meetings With Remarkable Men. Reading outlier philosophical texts was a favorite pastime of my grandfather's. Sometimes he'd draw these treatises back to spices, sometimes not. When the front of the store got cold during winter, we'd retire to the "sugar room," where the stock was kept for the half-dozen cinnamon sugar blends. The air was syrupy warm, an intoxicating blend of vanilla and sugars baking with cinnamon, maple, and violet.

For every time we ate whole sugar cubes (to which we'd add vanilla with an eyedropper), there were five times our senses were overwhelmed by spices in their rawest form. The "cinnamon challenge" had already been suffered by Spice House employees long before it came into vogue. I went off ginger for years after accidentally inhaling a huge lungful of the stuff in powdered form. On the other hand, my siblings and I still fondly remember the time my grandfather handed each of us a Malabar peppercorn with instructions to place it on our back molar and bite down. (If you try this at home, you will not enjoy what happens.) Other days would see him decide the time was ripe to ask his preteen grandkids to think on the nature of intelligence and where it comes from. From my birth to his death some 20 years later, the majority of my relationship with my grandpa unfolded against the backdrop of spices.

Even though neither my brother, sister, nor I went into the family business ourselves, it's impossible to have low standards when it comes to food. I'm not an asshole who brings my own grinder to restaurants (actually, no one in my family does that shit), but I'm not keen using other companies' inferior products either. I'm well aware of how annoying it is, yet I can't help but scoff at the generic store-bought spices, the dull cinnamons and old herbs, the disgusting pre-ground pepper turning to dust on shelves. (I know from firsthand experience how bad ground pepper is when it's languished on shelves for months or years. The whole sneezing from pepper thing only happens with nasty, old pepper. Freshly ground pepper will never make you sneeze.)

At work, I keep enough spices in my desk drawer to season my lunches, because I add something to pretty much everything I eat. You'll find lemon-pepper seasoning and sandwich sprinkle, a shaker of kosher salt, and a pepper grinder with backup peppercorns. (Seriously, pre-ground pepper is fucking gross.) My colleagues stop by to request a seasoning that can liven up a boring salad. I usually suggest mixing multiple seasonings. I use three blends alone on my pita.

The most popular seasoning at the office is North Face, a blend that's no longer commercially produced but which my grandma will whip up upon request. I use it all the time at home, but at work it's used almost exclusively on pizza. I like to think this is how I make up for lecturing my co-workers on the spice-related subjects dear to my heart, and the comments I can't let slide, even if they're trivial: Co-editor Laura M. Browning warns our co-workers never to confuse "spice" with "seasoning" lest they receive a lesson from me on the difference. (Seasonings are composed of spices.) But the truth is that I've only scratched the surface of knowledge about spices. I may know more than the average person, but my mom, aunt, uncle, and grandmother (and when he was alive, my grandfather) can school me any day.

It's been almost three years since I worked at the Spice House in Wisconsin—moving to Chicago to work at The A.V. Club put an end to that—but I still end up talking shop a lot. Below are the conversations that come up all the time, the topics I still feel passionately about, even several years and a state removed from my spice merchant origins. Use this information liberally, as you would spices.

Salt is salt

My grandfather used to say this all the time, and it's true. Salt brings out the flavor of the food, full stop. There are a great variety of salts, but the reality is they're all the same mineral. Coloration in salt comes from the minerals near the salt as it forms. There's nothing inherently better about colored salts, but the marketers selling you that stuff will try to convince you otherwise. I've seen pink salt promoted as an "alternative" salt that doesn't cause blood pressure issues. That's a lie. My advice is to buy kosher salt or the chunkier white salt if you like the crunchiness. If you really like the mild flavoring of gray salt, that's fine, just know that it's sold at a higher cost for what comes down to the same thing as my box of salt I can get for a couple bucks. And one more thing: All salt is sea salt.

Salt grinders are bullshit

I'm not done with salt yet: Don't put your salt in a grinder. All you're doing is making your salt smaller than it was before. Unlike pepper, which is actually processed in the grinder, salt does not need to be ground and is not fresher after coming out of a grinder. It's just smaller. Use a shaker.

Organic spices are a racket

There's a whole other piece to be written about organic spices, but the short version is that demanding organic spices is never going to be good for the farmers growing them. The U.S. standards for organic products amounts to ridiculously expensive and oftentimes unnecessary practices for small farmers who just don't have the resources to do it. There are plenty of ways to arrive at ethical treatment of animals and land that are not part of our complicated organic laws. And that's not to mention the people who demand organic products but will also freak out at the sight of a bug or won't buy something that's even a little bit misshapen or with a tiny brown spot on it. You can have pesticides or you can have pests.

Spices are a product of their country, culture, and weather

Discerning customers have complained to me in the past that the new cinnamon wasn't as brown as the old cinnamon. They weren't wrong, but we weren't trying to pull one over on them either. Spices are a crop, and like any other plant grown on farms, they're going to naturally vary from year to year. This happens most obviously with cinnamons, but it goes for all spices and herbs. Vanilla is expensive right now, due to geopolitics, weather, and the mafia. Yes, the mafia contributes to why you're paying more for vanilla now than you were a few years ago.

MSG is fine for you

The story of MSG is a true tragedy. The negativity associated with this delicious amino acid is due to a spurious study from 1968 that linked MSG with the "Chinese Restaurant Syndrome." This study connected that gut-bomb feeling you sometimes get after eating Chinese food to MSG, despite the fact that the typically cheap Chinese food prepared in American restaurants is fatty and served in large portions, and (like any restaurant), the food can be spoiled. My mom theorizes that lots of MSG was used to cover up the fact that, say, shrimp was a day past its prime, and that the sick feeling was due to the food but got blamed on the MSG. There's never been a scientifically rigorous study that's linked MSG with any negative effects. MSG should be used frequently and added to anything that needs the flavor drawn out, especially soups. But it enhances virtually anything it touches: Once, eating pizza at home, a friend scanned my spice rack and saw a jar with white powder whose label, in my grandfather's messy scrawl, read what looked like "MS6." He sprinkled it on his pizza and came to find me, telling me that whatever MS6 was, it was the most amazing thing he'd ever tasted. Yes, MSG makes even pizza better.

Spices don’t go bad

People ask when spices go bad, and the answer is they don't. Their flavors just fade over the years, faster when exposed to sun and heat. You'll see it. If your oregano isn't looking as vibrantly green as it was a year ago, well, the flavor is going to be lessened, but you can compensate by simply using more of it. Whole spices, like nutmegs, cloves, peppercorns, etc., will last a really long time—many years—without going bad if they haven't been broken open yet.

Vanilla isn’t vanilla

One last, minor thing: Vanilla is a deeply rich flavor that has unfairly become shorthand for boring, basic, and sexually unadventurous. Merriam-Webster's second definition includes the sad phrase "lacking distinction" to explain the term "vanilla." I'm not arguing that we drop this secondary use of the word—we're too far gone for that—but I do want to remind people that vanilla is actually an extraordinarily complex flavor. Chocolate is far more vanilla than vanilla.