Cooking A Perfect Ramen Egg Is No Magic Trick

There is irony to the U.S. fascination with eggs in ramen. Don't get me wrong. Few things in life are more delicious than a marinated, aromatic egg encapsulating a jiggly yolk.

My theory, though, is that they're more popular in the America than in Japan. I find this particularly strange, given the deep relationship Japan has to eggs. Japan is one of the largest producers of eggs in the world—some eggs are cultivated to be so rich you can pick up the raw yolks with chopsticks. Eggs in Japan are fetishized for having yolks with a deep orange, even reddish yolks, which are reflective of chickens' diverse diets (though some producers intentionally manipulate the color, as certain foods like red pepper will color the yolk deeply, in fact).

I don't think any aspect of the ramen process has been more overthought than eggs. Everyone has a different recipe, resting time, cook time, peeling method. The dirty secret is this: Ramen eggs are simple to make. They're bafflingly easy. It comes down to following a process.

The eggs commonly served in ramen have a number of names: Ajitama, Hanjuku tamago, Yudetamago, so on and so forth. For our purposes we'll just call them ajitama.

(Side note: This is different from onsen tamago, a slow-cooked egg named for hot springs, characterized by a liquidly white and yolk with a below-poached texture. They're called this because the eggs are cooked in a way as if it's been gently poached in its shell in the waters of a hot spring. As tasty as those are, I don't think they pair well with ramen, as they disintegrate into the soup and behave more like a sauce than a topping.)

I've done my fair share of ramen research, but the history of adding eggs to ramen is a topic on which even historians have a tough time finding consensus. For one, certain ramen styles omit eggs entirely. You'd almost never find an egg on a Hakata-style tonkotsu, which is rich enough as-is. In most ramen shops that do sell eggs in ramen, the egg is often considered extra—it's a nice add-on, but not mandatory to the overall dish. (In fact, I ate 22 bowls of ramen in Sapporo last September, and only five bowls included the egg as part of the price of their standard. And these were halves of eggs, not whole ones.)

But, they are delicious indeed. Here's everything you need to know to make them.

The eggs

You should use large eggs (large as defined by the U.S.D.A., which is a 2-ounce egg)—not jumbo, not medium. If the eggs are too big or too small, you'll need to adjust the cooking time. You should also buy eggs you enjoy eating—consider local farmers, as always. But remember: Yolk color is not necessarily an indication of quality.

The cook

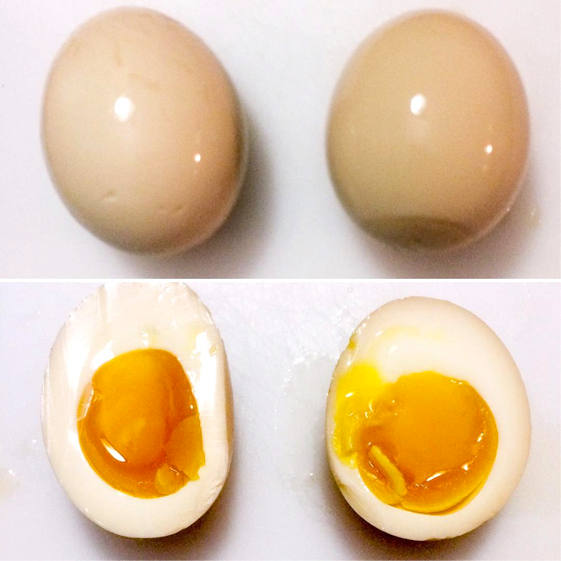

My goal when making an ajitama egg is to have an egg cooked to the following characteristics:

- A fully cooked white, pleasantly bouncy without being rubbery

- A yolk that is custardy, not liquid nor hard

Firstly, I want the white cooked to a different doneness than the yolk. To do this, it's in my best interest to blast the egg with rapid heat, so that the outside cooks rapidly, and the inside just begins to get warmed.

Water transfers heat evenly and quickly, so it's a perfect medium to cook in. This means, though, that sous-vide is not going to work for your classic ajitama, short of setting a circulator at a super-high temperature north of 200 degrees Fahrenheit. Whites and yolks firm up at different temperatures, with yolks firming up at a much lower temp than whites (around 140-180 degrees for whites, 149 to 158 degrees for yolks). Egg proteins can also firm up as time goes on, further complicating things (a yolk cooked at 150 degrees for an hour is looser than one cooked at 150 degrees for two hours).

For our purposes, we don't need to deal with such complexities. So into a rolling boil of water the eggs go. By the time the white is fully set (about seven minutes), the yolk is just starting to come up to temperature.

I also want to ensure that the exterior has as much time to cook without transferring heat to the yolk, because the yolk cooks faster than the white. To do this, simply use cold eggs. The cold interior of the egg is going to prevent that heat transfer from occurring too quickly, giving you more flexibility in creating the gradient from firm white to fudge-like yolk.

After the eggs cook, it's critical to shock them in ice water to stop all cooking. Again, we're aiming for a very specific texture, so the faster we can halt any carry-over cooking, the better. It might seem arbitrary, but an egg with a few more minutes of warmth pumped into the yolk can go from glorious runny goodness to a chalky yellow disappointment.

The brine

Now comes marinating the peeled eggs. Every recipe I've come across in the U.S. for ajitama insists on a dark soy-based marinade that you steep the eggs in for one to six hours. This is a large range, in my view. Letting the eggs sit too long in the soy may result in a grainy, cured yolk, as the salt changes the texture of the undercooked interior. A one-hour brined egg is going to taste different than one sitting for four hours, obviously. On the other hand, if you don't let the eggs sit in the brine long enough, the brine doesn't have a chance to penetrate the white very deeply, which means your yolk isn't really seasoned at all.

To control both of these problems, the simple solution is to make a weaker brine, which you can then let the egg sit in longer. This allows some of the salt to get to the yolk, seasoning it and giving it a denser, fudgier texture, without running into over-salting issues.

My ratio is one part soy sauce to five parts water. That gives the final brine an average salt content of around 1 percent (maybe a little more, I'm rounding!), so that after 24 hours or so, the egg is perfectly seasoned.

On peeling eggs

There's a lot of information out there about how to make eggs easier to peel. Here's what I know. Cooking the eggs long enough helps them peel better, because softly cooked eggs are, unsurprisingly, difficult to peel. So cooking them longer makes things easier.

Poking a hole on the heel of the egg seems to help with peeling. I have no idea why this is, it also helps prevent the eggs from prematurely cracking. So I also do this.

Shocking the eggs in ice water also seems to help. I do this for other reasons, like to halt cooking, but it does seem to make the eggs easier to peel. These all seem to work for me. Your mileage may vary.

The Ramen Lord’s “Ajitama” Marinated Eggs

This is exactly how I make ajitama. I highly suggest using a digital scale, which are inexpensive and makes your life so much easier.

- 6 eggs, refrigerated

- 500 grams water

- 100 grams soy sauce

- 80 grams mirin

Bring a large pot of water to a rolling boil. I use a large Dutch oven.

Once the water is boiling, remove the eggs from the fridge, and prick a small hole on the fat side of each egg. I've found this helps tremendously with getting the eggs to peel. You can use a thumbtack, a sewing needle, or even a special egg piercer.

Add your eggs to the boiling water, three at a time. The reason is adding all six eggs may lower the temperature of the water too much. Set a timer for seven minutes.

While the eggs cook, combine water, soy sauce, and mirin in a Tupperware container that you plan to steep your eggs in. Separately in a large bowl, prepare an ice bath. Once your timer goes off, remove the eggs from the water and place directly into the ice bath to stop the cooking process. Allow the eggs to chill for at least 15 minutes.

Peel the eggs. I like to crack the shell all over, gently tapping the fat side first then working my way around. Then, using the natural depression on the fat side of the egg, peel off the shell.

Add your eggs to the brine in the Tupperware container. If the eggs are floating, add a square of paper towel over the top. Cover, and place the container in the fridge and allow to sit for least 24 hours and up to three days.

To serve eggs in ramen, you can slice them in half lengthwise with a knife (vertically), and present them yolk side up. Or you can do as I do: toss one into your final bowl whole, which you then get to greedily pry open to reveal the delightful yolk inside. If you like your eggs warmer, you can remove them from the fridge 30 minutes ahead of time to temper or drop them into boiling water for up to 10 seconds to heat up.