The Complete Guide To Conquering Ramen Chashu

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

One of the best parts about ramen is the variety of toppings a bowl can include—this is where many chefs flex their creativity. It can be something as simple and classic as thinly sliced green onion, or toppings that add complexity such as fish powder or fried burdock root. Some toppings are expected, some are not.

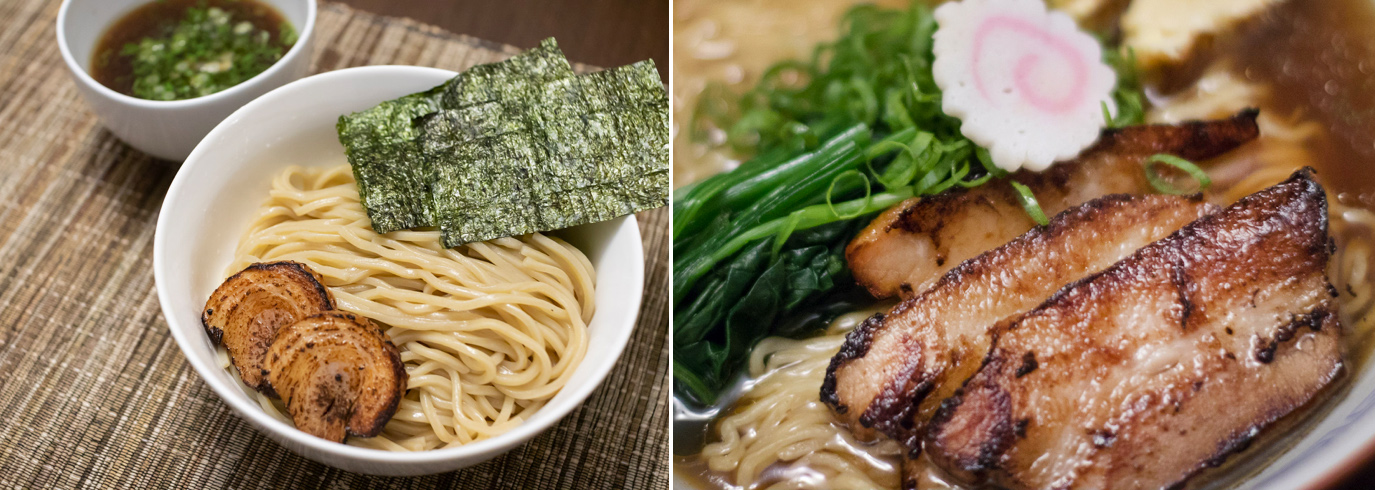

But perhaps the most ubiquitous of toppings is chashu (derived from Chinese char siu), a slice of meat that gently bobs on top of the surface of the ramen bowl. It's typically pork, as the name "chashu" specifically refers to the Chinese style of maltose-glazed roasted pork, though modern ramen shops can sometimes use chicken, duck, or even beef. Even those non-pork meats might be called chashu.

For the sake of our discussion though, we're going to focus on pig. Because pig is most common, and pig is delicious.

Chashu is so crucial that hardcore ramen nerds insist it be positioned in the 6 o'clock position of the circular bowl, to ensure the pieces of pork are front and center of the bowl, clearly visible to the guest. In America especially, I've found folks go crazy for this slice of melty, decadent meat that tops ramen. It slowly bleeds its flavor and fat into the hot soup below, quivering beneath the chopsticks as one picks up the tender slices.

If there was any topping more well known in the ramen world, I'd love to see it. A bowl of ramen without chashu feels empty.

As one would expect, there is actually quite a lot of depth to this pork, primarily in its preparation. So let's go over the styles and techniques ramen shops employ to deliver this slice of heaven to you.

The type of cut

Chashu is most commonly made from pork belly, with its thick bands of meat and fat layered on top of each other. It's relatively affordable, fatty, and flavorful. It's what bacon is made from. You like bacon, right? Do I have to convince anyone that pork belly is awesome?

The other alternative, particularly popular in more modern shops, is pork shoulder, specifically a small band of muscles commonly called "coppa," or "tubes and money muscle" in barbeque competition jargon. Here's the cut, in cured form:

This section of the shoulder contains a high level of intramuscular fat, which gives the meat that rich porky flavor. It also looks stunning, with little striations of fat encapsulating the various muscles. It's leaner than belly (because everything is more lean than belly), but still has enough fat to make for a succulent, delicious eating experience.

Lean cuts of meat, such as pork loin, is rare within ramen culture in Japan, so we won't focus too much on it. You'll occasionally see it in old-school places sliced thin, or in more modern shops looking to branch out of the stereotypes of fatty chashu. It's delicious if done correctly.

What you're looking for, in any case, is a piece of meat that is consistent in shape, that you can cook easily. Some folks tie up their chashu into rolls; this is to ensure even cooking, as well as to give it a neater, aesthetically pleasing appearance.

The cook

Once a shop decides on the cut of meat to use, they now have a host of options for cooking that pork. Despite the name suggesting "roasting" as the primary cooking technique, there are a multitude of techniques ramen restaurants actually use. For our purposes, the goal is to cook the meat so long that the connective tissue in the meat breaks down into gelatin, turning the meat lusciously tender. How far you go is up to you... but if you're like me, you want that melty goodness.

It's not the only goal. In some modern shops, the chashu is cooked until it reaches around 130 degrees Fahrenheit, so it's quite rare and pink. Called "rare chashu," it's then chilled and sliced, usually with a slicer. It's like bougie deli meat. It's delicious, but I'm guessing you don't have a professional slicer lying around (if you do, invite me over?). So we'll stick with the variety of chashu that you can make at home: tender, low and slow chashu.

Cooking tough cuts of meat is almost entirely about the relationship of temperature and time. And I'm going to shamelessly steal a lot of the science of meat from BBQ expert and all around good food dude, Meathead Goldwyn.

As the temperature of the muscle increases, the proteins denature, the muscle fibers squeezing up and releasing moisture, kind of like wringing out a sponge. In cuts without a lot of connective tissue (such as pork loin), this results in dry, chalky meat. For chashu made from muscles with plenty of collagen, that collagen converts to gelatin, which latches on to some of the moisture and coats the muscles in decadent meat juice.

Collagen converts to gelatin over time; this is not a process you can rush. And it's not entirely dictated by temperature. To be honest, I check chashu's doneness by using the ol' "touch it with your finger and see if it feels jiggly" test. Scientific, I know. It should feel pillowy soft.

With pork belly, this is not something you can over-cook. Much like in barbecue, a piece of chashu will reach, easily, above 200 degrees before being tender. That's okay. The gelatin is holding onto plenty of moisture, and the fat is giving that perfect, luscious mouth feel.

You have a few options for cooking your connective-tissue-laden meat:

- Roast it. I'm not a fan of this method. It's temperamental—if you roast too hot, the muscle will push out all of its moisture before the collagen has a chance to convert into gelatin (and let's face it, most home ovens aren't calibrated accurately).

- Toss it in the soup. Some places do this. They just take a hunk of pork, belly or shoulder, and throw it in the soup to cook. The soup gets the flavor of the pork, the pork gets the flavor of the soup. Then they fish it out when it's cooked. I don't love this method because the resulting pork, while cooked correctly, is completely unseasoned. You can soak the cooked pork in a tare of some kind, which is typically the move, but it always feels like a surface treatment. But it's definitely the easiest method. You don't even need another pot.

- Braise it in a flavorful liquid. This is my favorite. I usually use a quick soy sauce-based braising liquid, add some aromatics, and cook the chashu in it at a simmer until it reaches the texture I prefer. You can go full Western-style cooking and sear it beforehand if you like, or not. Doesn't matter. This braising liquid can later be used as the basis of a soy tare. So you win twice!

- Be a nerd and cook it in a water bath, a.k.a. sous vide. If you're a control freak, you can use the precision of an immersion circulator to precisely sous vide your pork belly. If you're into a firmer chashu, perhaps steak-like, this is the way to go, as you're able to convert just the right amount of collagen down, without converting all of it. For the melty tender stuff, braising is simpler, faster, and easier. Sous vide is also the method used for "rare" chashu, given the consistency a water bath can give you. For way too much on sous vide, I highly recommend Douglas Baldwin's book on the matter.

The chill and slice

Once the meat is cooked, it is critical to chill it thoroughly prior to eating. Almost no ramen shops slice warm chashu; it's always chilled down.

The reason for this is simple. Chashu, cooked long enough to convert the collagen to gelatin, is so tender and supple that it's difficult to handle while warm. Imagine trying to slice pulled pork. I don't care how sharp your knife is, this is maddeningly difficult to pull off. By contrast, when the chashu is cold, the gelatin within reverts to a solid state, which makes the resulting slices clean and easy. Think of it like slicing a round of Jell-O. It needs to be cold!

It's also nice because it means you can slice just as much as you need, which prevents the meat from oxidizing and turnings to an off-color. Kind of like why you prefer freshly sliced deli meat; that oxidization process impacts both look and flavor of the chashu.

Slice it as thick or as thin as you like when you're ready to eat. I like maybe a half-inch thick slice. Some places shave it paper thin and let it melt away into the soup. Others give you big hunks of chashu. Some places dice it up into cubes. The choice is purely up to the cook.

The reheat

Okay, you have some killer chashu. It's cooked amazingly, sliced perfectly. It's also ice cold. Which might be off-putting in a hot soup dish. You should probably reheat it. Here are four ways you can reheat chashu:

- Sear it

- Torch it (I like the iwatani torches, as do most American shops I know of)

- Let it poach briefly in soup

- Don't bother. Put it on the bowl cold. Me hungry. Give me chashu.

Whatever you do, hopefully you've heated up the chashu to the point that it's returned to its warm, succulent glory. I love a torched/seared chashu for that delicious browning action you get, but not every dish works with this. Shio, or other delicate bowls of ramen, as an example, might have trouble combatting with that intense, torched flavor. But it's always up to you, the cook.

I'm sure you're wondering, with all this information, can we get a recipe?

I've posted several different approaches to Reddit over the years. But consistently, as mentioned, the approach I gravitate to is the braise method. I have done braising exclusively at my pop-up in Chicago, called Akahoshi, and I feel it's been well received.

So being the generous ramen guide I am, I'm giving away the entire recipe for free. Competitive advantage, who needs it?

The Ramen Lord’s Chashu

- 2 to 3-pound slab of pork belly, skin removed

- Salt and pepper

- 1/2 cup Japanese soy sauce

- 1/4 cup mirin

- 1 cup water

- 1 Tbsp. brown sugar

- 1/4 cup sake

- 8 cloves garlic (or other aromatics you like, such as ginger, green onion, white onions)

- Depending on the thickness of your pork, you may want to roll it. Generally I roll the belly if it's less than 2-inches thick, aiming for a full roll around three inches in diameter. Simply curl the belly around itself, and wrap butchers twine to hold it in shape. Don't worry too much about how beautifully you tie it up, just make sure it's wrapped nice and tightly.

- In a saucepan, Dutch oven, or other lidded pot just barely big enough to hold your pork belly, sear the pork belly on all sides, over medium-high heat, around three minutes a side, turning to ensure even browning.

- While the pork cooks, combine the soy sauce, mirin, water, and brown sugar in a bowl.

- Once browned, remove the pork, set aside. Wipe the pan with a paper towel to clean out any residual fat that may have rendered out. You could also reserve this fat if you prefer, it's lard, and delicious. But you'll probably need to wipe down the pan for the next step.

- Deglaze the pan with the sake. If you didn't wipe down the pan, expect a grease fire, as the fat billows into the air as a cloud of small droplets of fat that is prone to exploding into a fire ball. So wipe down the pan before this step.

- Add the soy mixture, garlic, and pork, and bring to a simmer. Don't worry if the pork isn't fully covered, the steam will help cook the belly.

- Once bubbling, reduce the heat to low, cover the pot, and allow the pork to simmer until tender, around 2 1/2 hours, turning it occasionally to ensure the belly is covered by the braising liquid. I check the belly at around the 2:15 mark for doneness, prodding the pork to feel its texture. The fat on the outside should be very tender and yielding.

- Remove the pot from heat, allow the pork to cool in the liquid for one hour, before transferring to a container with the braising liquid and chilling in the fridge overnight.

Do you even need to put this chashu on ramen? I'd argue no. Add the precooked chashu as cubes to fried rice or stir fry. Put it on sandwiches. Just sear a few slices and eat it out of the pan because you don't want to dirty another dish.

Next up: How to achieve those perfectly molten eggs.