Why Recipe Exchange Emails Are Filling Up Your Inbox

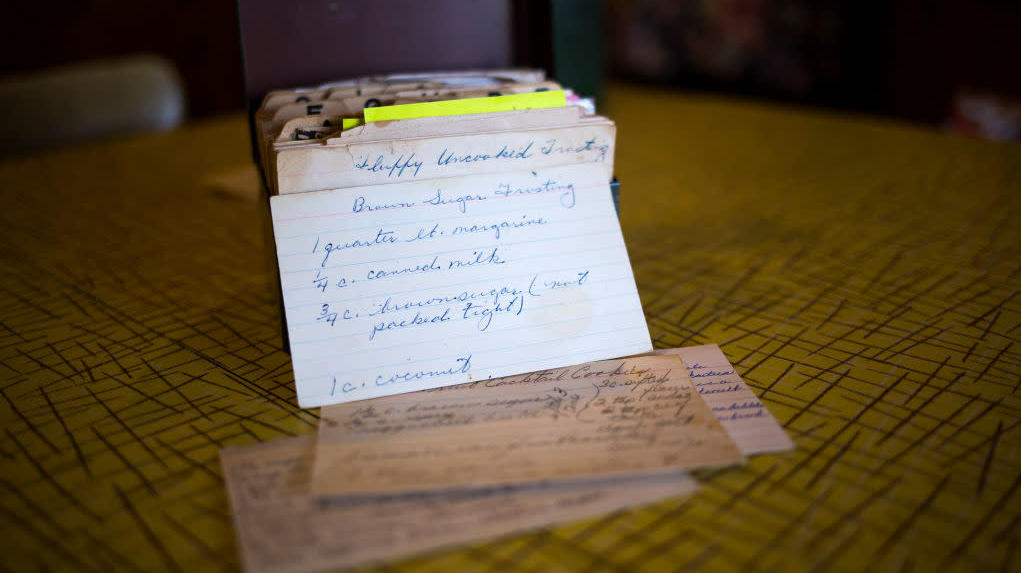

Even if your kitchen counter is crammed with every possible gadget and appliance, there's probably one thing it doesn't have: a little metal box full of handwritten recipe cards. First, Betty Crocker doesn't live with you. And second, thanks to the internet, you have instant access to every recipe you could ever imagine, plus a few you'd rather not imagine.

Yet recently you may have noticed your inbox filling up with recipe exchange emails that promise that if you email one recipe to the first person on the list, then forward the message to 20 more people, you'll end up with 36 new recipes. Why are we suddenly interested in sharing recipes instead of searching for them? Short answer: Quarantine does strange things to people, including transporting them through a collective wayback machine to an era of sourdough starters, banana bread—and recipe exchanges.

While we've been unable to find a recipe exchange Sender Zero to confess to starting all this, we found a range of opinions among those who've received the message. Some said they find the phenomenon annoying, some like the concept well enough but never get themselves mobilized to participate, and others took a shot and sent a favorite recipe out into the ether.

In the "sure, why not?" camp is Clay Williams, a New York City–based food photographer. He cooks, his wife doesn't, and when they were both busy in the Before Times, they'd often just get takeout. Now cooking has moved from creative expression to everyday chore. He had never before participated in a chain letter—"In college, I was always the one to break the chain and let them die," he jokes—but after weeks of sheltering at home, he needed cooking inspiration.

For the exchange, he sent a recipe for French onion slow cooker roast beef. While he didn't get the promised 36 new recipes, he received a few that he might just make, including one from food and travel writer Alisha Miranda that included a story she'd written about a Puerto Rican dish from her childhood. It also inspired him to buy Coconuts and Collards, a Puerto Rican cookbook.

"Traditions like this started with 1950s housewives, when you had to cook meals every day, no matter what," Williams explains. "Those ladies didn't have the luxury of saying, 'Let's call out for pizza,' and my wife and I are trying not to do that right now, either. But food still has to get made."

Sarah Peterson, who blogs at Vintage Dish and Tell, agrees that the exchanges are pure nostalgia. They offer up safe, cozy feelings, even if the message arrives through technology. "People are craving comfort food and looking for recipes that remind them of home," she says. Still, not everyone, even a nostalgia lover, makes time to participate in an email recipe exchange. Peterson received one but admits that she let the message slide to the bottom of her inbox and never got around to responding: "I feel so guilty, but I just didn't do it."

For Michelle Trench, a senior marketing director at a healthcare company in Minneapolis, the impetus to participate was more about the camaraderie. "It has to do with a feeling of solidarity, that we're all in this together," she says. She sent out a slow cooker French dip sandwich recipe, but got just a few back in return. Still, she feels positive about it. "A couple friends included me in the recipe they sent to the number one person on the list, which was nice," she said. Now that she's found herself cooking things she never bothered with before, including pizza crusts, pretzel bites, and crust for a quiche, she feels sure she won't be going back to store-bought versions. And she's become the kind of person who actually thinks a recipe exchange is peachy keen. "It's like I went back in time," she says.

The experience isn't always positive. "I participated in one started by a friend," says Meghan Holmes, a freelance writer from New Orleans, "and I got only one recipe back, which turned out to be from my own mom. It was a recipe for microwave chow mein that called for cooked pork—or 'other meat'—that's microwaved on low for 22 minutes. I'm not sure if she was joking or not, to be honest."

Leah Hammond, a food writer from Washington D.C., says, "I got four of those messages and then got so stressed and deep into the rabbit hole trying to choose recipes that I never replied."

Some have adapted culinary sharing in a new way. Emma Baar-Bittman, who lives in Northampton, Massachusetts, has worked at many top-tier restaurants, including Momofuku in New York City and Spoon and Stable in Minneapolis. She's just completed a degree in social work, and she came up with an idea that makes sense for someone with her background. It's a not-really-an-exchange project that combines caring about food and caring about other people. She asked friends from around the country to tell her what they've been cooking each week. She curates their responses and distributes a weekly set of stories, like the saga of a sourdough starter one man thought he'd killed, but which rose from the dead in a quarantine miracle. Another friend made a bulk order of gummy candy from Economy Candy, then provided rankings for each variety.

Hannah Selinger, a food writer in New York, is one contributor. "A recent story started with, 'I made a straight-up inedible dinner this week,' and it was a really good story," she says. Still, she senses a shifting mood as the weeks have passed. "People have gotten sadder, I think, and less ambitious."

Baar-Bittman agrees: "We're entering a new phase in which this seems like it might be a longer haul. Writing it all down makes it seem like we're living in a special time, when, in fact, it may just be the way we live now. Still, it makes me feel connected, so I'll keep doing it until it stops bringing me joy or until nobody wants to participate."

There are deeper motivations at play, too. Leah Samler, a psychologist and adjunct faculty member at Pepperdine University, says that restaurant shutdowns and grocery shortages have left many of us experiencing food scarcity, or at least the fear of it. "The more we think about food, the more we want to talk about it, and these exchanges are one way to do that," she says. "Sharing food, recipes and the stories behind them helps foster a sense of community, which can be therapeutic and healing. And learning how to make new meals provides a feeling of accomplishment that you're nourishing yourself, family and friends."

Samler hopes that that, along the way, the process can become even more personal: "I'd love to find a way to share those handwritten recipe cards. Someone will have to invent that system for an online format."

Clay Williams’ French Onion Roast Beef

"This recipe got its name because I first made it with leftover broth from French onion soup," Williams says. "It's not exactly quick, but it's pretty easy and delicious."

- 1 beef chuck roast (3-5 lbs., whatever size can comfortably fit in your baking vessel)

- 1½-2 cups onions, sliced (can be a mix of white, yellow, Vidalia, and shallots)

- 3-6 garlic cloves, smashed flat

- 1-2 Tbsp. olive oil

- 1 Tbsp. butter

- 2 Tbsp. neutral oil

- 2-3 Tbsp. butter

- 1 Tbsp. flour

- 1 quart beef stock or leftover soup broth, ideally super beefy

- Kosher salt

- Black pepper

Preheat oven to 250 degrees Fahrenheit.

Pat the beef roast dry. Season all over with fresh ground black pepper and salt. Let sit in the refrigerator overnight, preferably elevated on a rack, or at least while onions caramelize.

In a Dutch oven or heavy lidded pot, warm 1 Tbsp. olive oil over medium heat. When it shimmers, add onions and smashed garlic cloves. Sprinkle with salt and add butter. Stir everything together. Lower heat as far as possible and let cook for at least 30 minutes, up to 90 minutes, until onions are soft and sweet. If onions start to dry out, stir and add a little more butter or oil.

Add neutral oil to a skillet, heat to high, and swish around until oil coats the bottom. Pat beef roast dry again. Add to hot pan, searing on all sides. While beef sears, pour stock over onion-garlic mixture and bring to a simmer. Stir, scraping up any crispy onion bits on the bottom.

Once beef is seared, add it to onion mixture in the pot. Ladle about half a cup of stock from pot to the skillet, scrape up beef bits and pour back into pot. The liquid should nearly cover the beef. If it doesn't, add water or more stock.

Cover with lid and roast for 3 hours. Check for tenderness, and if it doesn't melt, give it another hour or so. (If you wish to cook the beef in a slow cooker, it will cook on the lowest setting for up to 24 hours.)

Once tender, remove roast to an ovenproof skillet. Surround meat with what's left of the onions and a ladle or two of the cooking broth (up to a cup). Preheat the broiler.

Place skillet under the broiler for 5 minutes, until beef crisps up again on the edges.

Remove roast to platter. Simmer sauce with 1 Tbsp. butter and 1 Tbsp. flour. Stir to thicken. Pour over roast and serve.

Strain and freeze remaining cooking liquid for your next roast. Keep the fat on top for searing beef and caramelizing the onions.

Michelle Trench’s Slow Cooker French Dip Sandwiches

- 2-3 lbs. beef chuck roast, fat removed

- 1 can French onion soup

- 1 can beef consommé

- 1 package dry onion soup mix

- 1 cup water

- Hoagie rolls

- Provolone slices, if desired

Combine soups, soup mix, and water. Place beef in slow cooker, pour mixture over it, and slow cook on low for 6-8 hours. Slice and place on toasted hoagie rolls. If desired, top with slices of provolone cheese and broil the sandwiches until the cheese melts. Serve with a side of the remaining juices for dipping.