It's Not My Family's Thanksgiving If We Don't Destroy A Turkey

I'm no longer fooled by the 150-watt sheen of fresh snow and symphony of silverware on fine china—I know that the holidays are ripe for every strain of disaster. Old wounds open like oven doors, ancient grudges unearthed along with boxes of ornaments, grief burns as hard and fast as a forgotten sheet of break-n-bake rolls.

It's during these months when we lean on the pillars of tradition, time-tested and long loved. A family with historical nearsightedness, one with slapdash origin stories and six-feet-under secrets, the Shreibaks have never managed to uphold traditions, especially food-based ones. The precarious ties that bind us cannot handle the heat, so we follow sage advice and stay out of the kitchen.

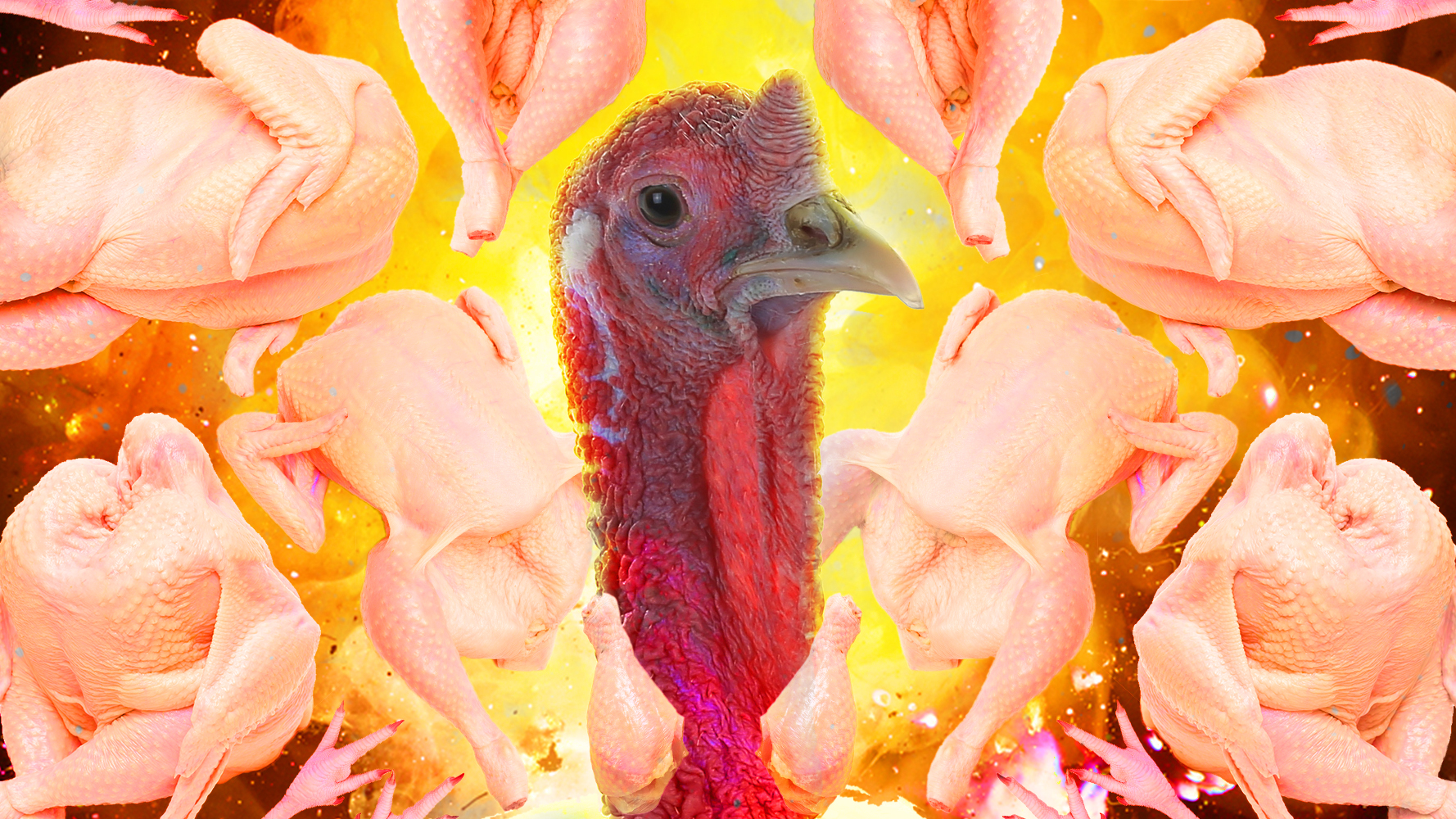

One notion of tradition is granted for Thanksgiving dinner, in that it always yields some sort of poultry-related crisis. We've probably sacrificed a small homestead's worth of birds to gallons of hot oil and hastily chosen beer cans and coals that glow as bright as Santa's suit. As the holidays draw nearer, so does our hunger for chaos. Thanksgiving dinner never fails to sate our appetites for destruction.

The last Thanksgiving I ever spent with my Ma's family ended in flames—there was no other way to leave them. Under the influence of myopic ambition and a couple glasses of wine, my Aunt Nancy thought that frying a turkey in her sunroom would create the excitement needed to cut through the hedge of resentment that divided us. I could barely contain my preteen skepticism as she lowered the bird into a metallic cylinder and boldly proclaimed, "Set it, forget it."

We would never forget this turkey. As I was shaking a mason jar full of cream in her kitchen—another one of Nan's batty bonding activities was forcing us to churn butter by hand, which always resulted in a jaundiced mess of cream and salt—I remember feeling a bead of sweat slither down my neck. No, I wasn't taking my assignment too seriously or buckling beneath the tension of the inter-cousin screaming match unfolding before me. The curtains were on fire.

Along with the dingy pot housing the bird and a gallon or so of piping hot oil, my family, too, erupted. The ribbons of flames became indistinguishable from the tufts of autumn leaves just beyond the sunroom windows, leaving us hungry for more than just turkey.

From the moment when Ma was told that her heart was too big, she became a woman living on borrowed time. Life proceeded to exist in phases of Before and After, the holidays becoming my mother's celebration of all things simple yet improbable. When the Gary Works steel plant fumes began to prick the autumn breeze, Ma would begin organizing a grand pre-Thanksgiving dinner for our family of four.

Surrendering to years of dangerously rare, salt-smacked Cornish hens, she decided to err on the side of audacious and adapt the classic Beer Can Chicken concept to turkey. Valiant as her efforts in the kitchen had always been, there was a glaring flaw in her master plan: Ma was a teetotaler who didn't know jack shit about beer, so she just shoved a leaky Coors Light up the bird's cavity and thought nothing of it. The result was a gummy pile of khaki-colored meat that no amount of garlic salt of lemon juice could remedy. We laughed until our stomachs hurt and eclipsed the hunger pangs pulsing through us. We laughed until we were left with nothing but our love for each other to feel warm and fed.

In 2008, our family saw three matriarchs die in the span of 18 months and nearly all of us were left without a full set of parents. The first Thanksgiving after losing someone is always an exercise in subtraction. Empty chairs, quieter conversation, fewer place settings to be washed and spit-polished. It was during this year and a few that followed when nothing was spectacularly awful about the turkey. There were definitely tears and some smoke, but it barely mattered. Our hearts were tired, our stomachs were hollowed, we were fumbling through recipes left in dead women's mud-clear scrawls. None of us had been hungry for much of anything.

Making a family isn't so different from following a recipe. You need all the right ingredients, a blind willingness to abide by someone else's instructions, and an unwavering faith that things will all work out in the end. When it came to my first Thanksgiving with my dad's girlfriend's brood, that was a recipe for disaster—and Trash Can Turkey.

Our first Thanksgiving as a trio of misfits shoehorned into a foreign family, nerves were frayed and tensions were concrete-thick as my brother, Dad, and I ambled into his new amour's backyard. This new clan was digging a hole fit for a grave. Burt, chewing on a cigar nub like a cow on cud, welcomed us into his sister's home with a handshake and a shovel.

Hours were spent bickering over seasoning strategies, balancing the bird upright on a precarious tin-foil spear, spending awkward silences staring at a glorified gutbucket engulfed in flames. At some point I made an ill-advised joke about it all being a metaphor for something, spoiling much more than the turkey roasting at our feet.

Like most young adults trying to rewrite their own histories, my brother and I had not learned the past's mistakes. Once we'd graduated from ramshackle dorms to our own shabby apartments, we attempted to coordinate extravagant three-course meals of wellingtons and roulades and whatever Gordon Ramsay was raving about at the time. Inevitably, I would take my cocktail mixing (and drinking) duties far too seriously, and Ryan would morph into a scorned chef anxiously weaving bacon into plaits and fussing over aioli. No matter how hard we tried to fight it, we were kitchen catastrophes bonded by blood.

Our most spectacular failure was our one and only Friendsgiving. After procrastinating his turkey-buying responsibilities, my brother rolled up at my doorstep an hour late with a frozen 20-pound Butterball that would spend the afternoon steeping in a square-foot sink. My kitchen didn't boast nearly enough counter space to accommodate our delusions of culinary grandeur, so each dish was precariously stacked like a game of high-stakes Tupperware Jenga. The whole celebration ended with us all wine-buzzed and arguing over whether we should watch Thankskilling (Ryan's choice), or Planes, Trains and Automobiles for the 23rd time (my choice, forever and always) as we navigated around undercooked meat.

Tradition can exist in negative space, can simply be the notion of mutually assured culinary destruction. Every year, I know that the turkey will be as dry as sand and bone. That the air will be tinged with brackish oven smoke and a sharp whiff of wine tannins. That nothing will be perfect, but we are alive and sitting in the same room and that is enough. That's what family and cooking have in common—they both teach you how to laugh in the face of fire.