Raisin D'être: Is It Worth It To Dry Your Own Grapes?

Raisins once enjoy a favored place in society, as evidenced by the fact they were distributed as prizes in ancient sporting events. But they occupy a weird place in our present food landscape. Are they a snack or an ingredient? Delicious treat or lunch box cast-off? And are millennials killing them? Earlier this year, Sun-Maid leaned heavily into nostalgia-based marketing to ask us, essentially: Hey, remember raisins?

Americans seem more enthusiastic about grapes, which come in colorful bunches beautiful enough to sit in the center of our tables like the subject of a still-life painting, and appealing enough to be the preferred snack of supine, decadent emperors. And, it bears stating, raisins are just dried grapes. It's a fact I must have first learned at a young and impressionable age, because I vividly recall leaving a bowlful of wet, white grapes to bask in the sun on our backyard patio with hopes they would turn to raisins, yet finding only disappointment an hour or two later when I returned to find hot, wet, white grapes, which I promptly ate.

When I recounted the episode years later with high school friends, they laughed at me. People seemed to find the whole enterprise the height of folly, as if I was telling my friends to wait 30 minutes after eating to swim. My raisin experiment remained a joke for many more years.

The particulars of raisin-making, and why I initially failed at it, would elude me until intrepid reporting led me to uncover the steps on a webpage devoted to science experiments for children aged 11 and under. Having now mastered its secrets, I feel qualified to dispense this ancient scientific wisdom, so let's get that out the way.

Grapes have a high sugar content; nearly three-quarters of a grape's total weight can come from sugars. They also contain natural acids. This makes them ideal candidates for sun-drying in favorable weather, defined by the National Center For Home Food Preservation as a stretch of days with temps at or above 85 degrees Fahrenheit, which you may know as summer. Humidity is also in play, with a preferred dew point below 60. Environmental requirements go a long way toward explaining why California's hot, dry San Joaquin Valley is home to 100% of U.S. raisin production.

But raisins can be made wherever these conditions exist. Moisture held by grapes will vaporize when left in the sun, causing the skins to shrivel, and left behind, sugars crystallize inside the shrinking skins, completing the transformation of watery, bulbous grapes into plump, dimpled raisins.

Sounds easy, right? In theory, yes. In practice, no. The "children's experiment" label led me to believe this trick could be pulled off in as little as three days with just a baking tray, a cover and some moxie. What began as a proverbial three-hour tour became a weeklong odyssey. I'm no budding 11-and-under Gregor Mendel Jr., but I can say with certainty grapes require more than three days to transmogrify into raisins. Some further and frankly too-late sleuthing led to a newly realized horror that this one mom somewhere kept grapes in a dish for 64 days before she deemed the wrinkly nuggets that sat before her to be raisins.

My method

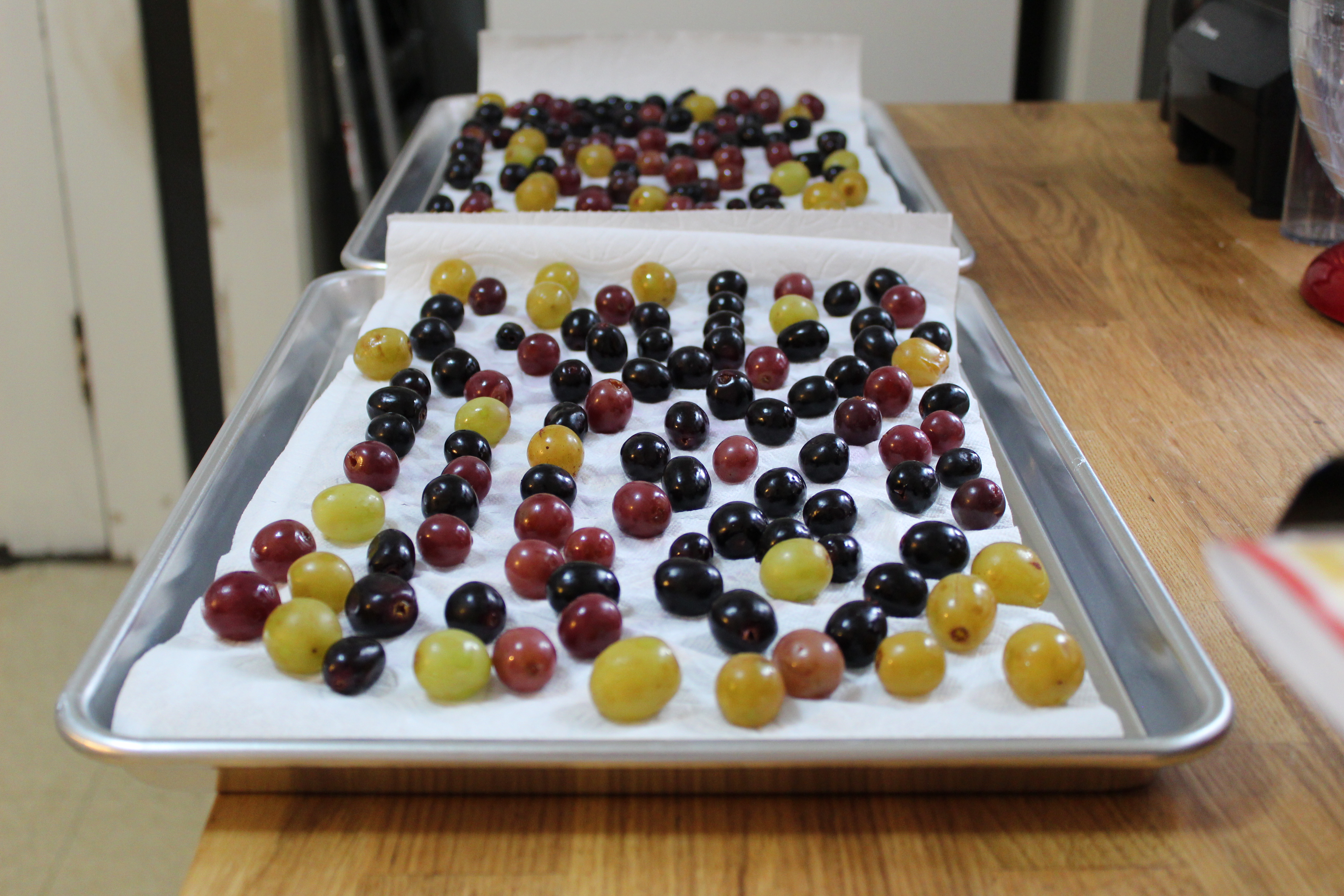

Using an assortment of red, black and green grapes, I kicked off my Great Raisining by rinsing the fruits and covering them with aluminum foil atop a baking sheet, taking heed of the command to let no grapes touch.

Within a day I realized the foil was no matched for invading armies of bugs, so I swapped out the cover for some spare pillowcases. That solved one problem, but three days later, the grapes were still definitely retaining their moisture, and had only begun to pucker.

Thankfully, I then stumbled onto a real breakthrough. Issac Newton had his apocryphal apple; my Eureka moment came from discovering the inside of my car was hot. So I moved the trays into the back of my Honda CR-V and let them bake for another three days.

A week had now passed. While this latest tinkering had accelerated the dehydration, only a handful of grapes appeared to have reached the actual Raisin Point. Keeping raisins wrapped in the hatch of my CRV until the moment of summer's farewell kiss would be preferable, but I was up against a deadline, and having dropped $10 on grapes, I wanted to cash this freelance check. I made the decision to spurn nature and sell my soul to electricity, placing a tray of the most resistant grapes in the oven set at the lowest possible temperature overnight. That did it.

(Even if I hadn't cheated with the overnight shortcut, an oven or freezer is still necessary to safely complete the raisin drying process. The National Center For Home Food Preservation recommends freezing homemade raisins for 48 hours or baking them for 30 minutes to destroy any insect bits that might be present).

The results

The final product tasted less stiff and sugary than store-bought raisins packed in cardboard containers, not to mention they were two to three times the size. The texture and flavor was a dead ringer for fruit leathers. The distinct raisin taste held notes of the fruits former life as a grape. They were perfect in oatmeal cookies, packing a sweetness equal parts fruit sugars and the realization of a childhood dream no longer deferred.

What I learned

- Yes, there were some issues with mold. I attribute my issues to not drying out all the grapes properly after I rinsed them. It's also possible that the weather might not have been hot and dry enough to bake the white grapes, which have a slightly lower sugar content than black and red varieties. The white grapes I bought from the store were not the best either, already past their peak and appearing brown in spots.

- Leaving the fruit outside was not optimal, according to the National Center For Home Food Preservation. Cooler nights allowed the raisins to wick up wetness and stave off their inevitable, dry fate.

- The aluminum tray also was not optimal, as it has a tendency to discolor and corrode and may have caused some of the casualties during the drying process. The National Center For Home Food Preservation recommends enclosing grapes between two screens made of stainless steel, Teflon-coated fiberglass and plastic.

- Golden raisins are just regular white grapes that have been treated with sulfur dioxide to retain their color.

Worth it?

Admittedly, drying your own raisins approaches DIY mustard territory. And the setup, while minimal, does require materials that probably aren't worth investing in just for the sake of hot-boxing grapes.

That said, the saving grace is the passive element and the payoff. If you're not pressed for time and are lucky enough to live in the right climate and have extra space, say a potting shed or a three-seasons room, then go nuts. In a couple of weeks, you'll be rewarded with large, succulent dried fruit with a gummy flesh that easily surpass the smaller, harder, sugary store varieties.

Otherwise, the oven/dehydrator trick is your best bet if homemade raisins are crucial to whatever scheme you're hatching at the moment.