How WWI Food Propaganda Forever Changed The Way Americans Eat

Meatless Mondays. Local is best. Eat less wheat. These sound like food fads plucked from 2017's buzziest blog headlines but are in fact from 100 years ago. Each was a campaign from the U.S. Food Administration during World War I, and the food propaganda it represented was as important to the war effort as Uncle Sam's "I want YOU for the U.S. Army." As young men fought in the trenches of Europe, housewives across America were called upon to do their duty by minding the pantry, keeping down food waste, and foregoing the bounty of our amber waves of grain so that the boys "over there" could be fed. Unsung and nearly forgotten, the food calls to action from World War I paint a vivid picture of conservation and volunteerism, early nutritional science, and the birth of advertising. Not surprisingly, some of those behaviors—keeping backyard chickens, using dried peas as a meat substitute—have reemerged in 2017 as in vogue food trends.

For Americans in the early 1910s, access to food was not a major concern. Rural meals revolved around a hearty farm diet rich in meat, produce, sugar, and fats, while city dwellers had access to myriad restaurants as well as both fresh and packaged convenience foods—like Kellogg's Corn Flakes and Oreos—for dining at home. The food supply was so ample, in fact, that when World War I broke out in Europe in 1914, the United States' first response was to become the foremost supplier of food relief aid. Hard-hit countries like France and Belgium received dedicated shipments, and private organizations spent more than $1 billion to distribute 5 million tons of food across enemy lines.

The focus of this food delivery infrastructure changed, however, when the U.S. entered the war in 1917. Although aid to allies continued, the primary concern became feeding American troops, and feeding them well. A typical daily ration for a U.S. infantryman during the Great War consisted of up to 5,000 calories made up from a pound or more of meat (bacon or fresh meat, rather than canned, when possible), 20 ounces of potatoes, and 18 ounces of bread (often produced in nearby field bakeries). This was about 20 percent more than the French or British could supply their men, and considerably more than the Germans, especially in the final months of conflict. This food often came straight from the homeland, and supply lines crossing the Atlantic were considered as important as the lines across Europe.

At the behest of Congress, President Woodrow Wilson created the U.S. Food Administration (USFA) to manage the food reserves for the U.S. Army and allies. He appointed Herbert Hoover—then just a private citizen, a mining executive who had left his job to lead the Belgian relief—to serve as the sole director, and Wilson afforded him wide latitude to accomplish the group's goals. Although the mission was to keep troops fed, this charge required a tremendous amount of intervention in the food habits Stateside. Hoover became known as America's "food dictator." The USFA fixed the price of wheat (both so that it could buy and ship in bulk and so it could stabilize the price for worried farmers), commandeered rail lines to improve transport routes, and intervened to prevent food monopolies. Hoover even insisted he receive no salary despite the tremendous amount of work; he felt this allowed him a higher moral ground from which to ask U.S. citizens to make hard sacrifices.

Lucky for Hoover, Americans were primed and ready. Vilification of all things German was rampant—sauerkraut had been renamed "liberty cabbage," while hamburgers became "liberty steaks"—and the spirit of volunteerism that led to so many ally relief efforts in the first years of the war remained strong when attention turned to U.S. lives on the line. To ensure that support for the war remained high, Wilson authorized the creation of the Committee On Public Information (CPI)—a literal propaganda factory—just days after the U.S. officially entered into combat. The CPI produced press releases and worked with academics to write snappy informational pamphlets, and they coordinated the deployment of volunteers known as Four Minute Men. These public speakers—the CPI had nearly 75,000 nationwide—would appear in parks and churches, at social gatherings, or in vaudeville or film theaters to provide quick lectures (no more than four minutes) on everything from liberty bonds and the necessity of the draft to the importance of food conservation and the patriotism of growing one's own vegetables. It is estimated that Americans heard more than 7.5 million such speeches in the year and a half the program ran.

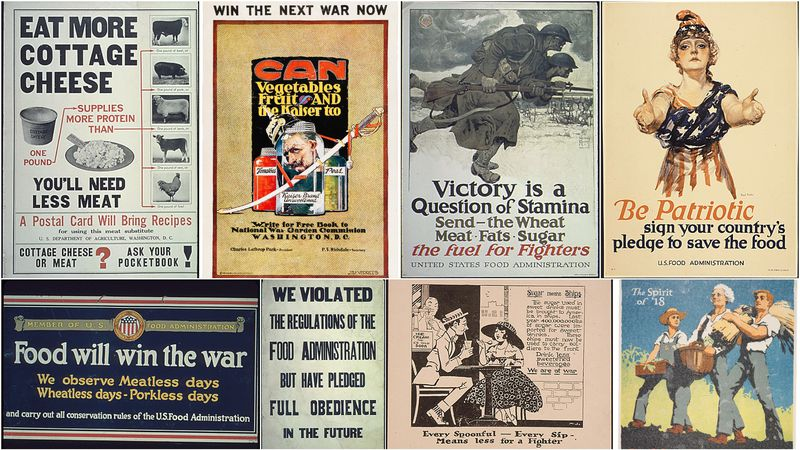

The food propaganda war, however, was most doggedly fought through the visual arts. The CPI had a dedicated wing that churned out nearly 1,500 posters and buttons over the course of the war, and the USFA created so much art that it filled the more than $19 million worth of donated advertising space. The main message was clear: "Food will win the war. Waste nothing." Wilson and others in the administration worried about the toll on morale that forced rationing would take, so these organizations acted to coax Americans into voluntarily cutting back rather than directing them by law. Homemakers (and even schoolchildren) were asked to sign pledges to conserve food and eat less meat, wheat, sugar, and fats, and peer pressure—Hang your sign in the window! Wear your pin!—applied the heat to keep promises.

In addition to the message of conservation, the posters also highlighted other rationale for changes in food policy.

Nutritional science was a burgeoning field and worked its way into the national propaganda by way of suggested food substitutes; with so many staples off limits, what were Americans to do to feed themselves properly? New products were developed and marketed—vegetable-based Crisco, for example, replaced precious lard—and unusual sources of protein were tried, including dried peas in place of beef, a trend which has returned today.

Not all these substitutions stuck. "Sea steak" and "sea beef" (whale and porpoise, respectively) were enjoyed but hard to come by, and a whole category of substitution-based dinners (so-called "victory dinners") popped up in cookbooks and magazines. Wheat cereals gave way to oatmeal or rice mixed with milk, and domestic honey or maple syrup replaced imported sugar. Baking had to do without eggs (try vinegar and water), butter (try oil), or wheat flour (try rye, oatmeal, or barley), and hearty salads, nuts, and fish replaced red meat and pork for main dishes.

Homemakers wanting to do their part looked for alternatives to their traditional pantry staples, but the problem became where to find such exotica. Local markets were used to stocking a limited number of items, and they required a number of employees—to fetch the food on each shoppers list, to ring up the purchase, and to deliver the items. With able-bodied men in short supply and demand rising for a greater variety of patriotic foods (hominy, buckwheat, margarine, and canned seafood, to name a few), full-service local shops began to give way to self-service "supermarkets." The first such store—Piggly Wiggly—introduced aisles of food open to the customers, individually price-marked groceries, and checkout lanes. By placing the workload on the customer, these new enterprises were able to offer more diversity of food and lower prices than the traditional corner shops.

Substitution could only go so far, though. Vegetables and fruits were needed both abroad and at home, and a parallel push was made for families to adopt an attitude of produce self-reliance. Hyperlocal food production took off as states and municipalities campaigned for "victory gardens" planted in backyards and in parks, and posters encouraged individuals to enlist as a "soldier of the soil." It was popular to try to keep chickens (for eggs and meat), and children could join pig and sheep clubs, where they helped raise the animals on county and state farms. For a while, even Wilson got in on the action and let sheep graze on the White House lawn. The rhetoric was fierce. "Every garden a munition plant." "Food is ammunition." "Sow the seeds of Victory!"

Harvest excesses were dried, pickled, or canned so that food was available in the lean months, and natural fruit jams (with no extra sugar added, of course) lined pantry cupboards. Some even went further and donated their homemade preserves to supplement the wholesale supplies sent to troops.

When the war ended with the signing of the Treaty Of Versailles in 1919, the U.S. Food Administration and Committee On Public Information both disbanded, but the food discipline learned by Americans would be vital over the coming decades. Nutritional science continued to develop in the 1920s as home economics departments sprouted up across the nation, food shortages brought on by the agricultural collapse of the Dust Bowl contributed to hardship in the Great Depression of the 1930s, and the return of conflict in the 1940s revived the sentiment that "food will win the war." Even today, vestiges of America's early food propaganda remain; consider Michelle Obama's planting of a White House vegetable garden and her efforts to fight child obesity or the USDA's evolving dietary guidelines with the Food Guide Pyramid and MyPlate.

The recipe of one part coercion to two parts patriotism might make some of the messages from World War I taste stale today, but there is no denying that many of the ideas of the era—such as supporting local agriculture, preserving fruits and vegetables, eating alternate proteins, and fighting food waste—are on the rebound. Some flavors linger.