Forget Sourdough—have You Tried Making Nukazuke Pickles?

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

About a week into the COVID-19-related stay-at-home orders, I noticed a surge in Instagram posts related to sourdough starters, beer brewing, and kombucha culturing—all forms of easy, at-home fermentation. The trend grew so quickly that the #fermentation Instagram tag receives fresh photos every few minutes; the sourdough tag is up to almost 3 million posts.

As the longtime keeper of a sourdough starter, I found this unsurprising. Fermentation is a time-consuming process that requires few materials and an open schedule—all characteristics of a pandemic-friendly kitchen project. I began culturing my sourdough starter during a stretch of unemployment; the endeavor injected structure into my otherwise unpunctuated life of Netflix, exercise videos, and endless social media scrolling.

But while baking and brewing comprise most fermentation social media posts, I noticed one item missing from the deluge of photos, not yet on the minds of home cooks: fermented pickles. Specifically: nukazuke pickles.

Nukazuke, or Japanese rice bran pickles, are a sour fermented pickle ripe with opportunity for a quarantine kitchen experiment. The process dates to 17th-century Japan, where it was developed as a method for putting rice bran, a sake byproduct, to use. It requires daily upkeep, but when it's done correctly you can pickle vegetables in just a few hours.

Unlike most store-bought pickles, nukazuke is made without vinegar. Instead, vegetables are buried in a cultured bran bed called a nukadoko, made from bran mixed with salt and water to create a paste that resembles wet sand. When food scraps are buried in the bran, the nukadoko becomes inoculated with lactobacillus bacteria, which naturally occurs on vegetable skins. According to Adam James, an Australian fermentation expert and founder of the popup Rough Rice, the nukadoko becomes more acidic as the bacteria multiply, eventually reaching the acidity required to create pickles.

"It's a continuous pickle machine," says Rosemary Liss, co-founder of Le Comptoir du Vin, a restaurant in Baltimore, and an artist who incorporates fermentation into her work. "The bacteria [in the nukadoko] feed off the yeast on the vegetables, allowing for a very quick cycle of fermentation."

The nukadoko is not unlike a sourdough starter: it requires constant care and hosts the same bacteria. However, you won't need to source flour or yeast to try this type of fermentation—an important consideration as grocery store baking aisles remain empty around the country.

Home cooks can create their own nukadoko inside household containers (wood is traditional, but enameled metal and plastic also work well), often within a week or two using common pantry ingredients. Plus, they get to bury vegetables in a substance that looks and feels like wet sand. "There's a tactile quality that's really nice about it," says Liss.

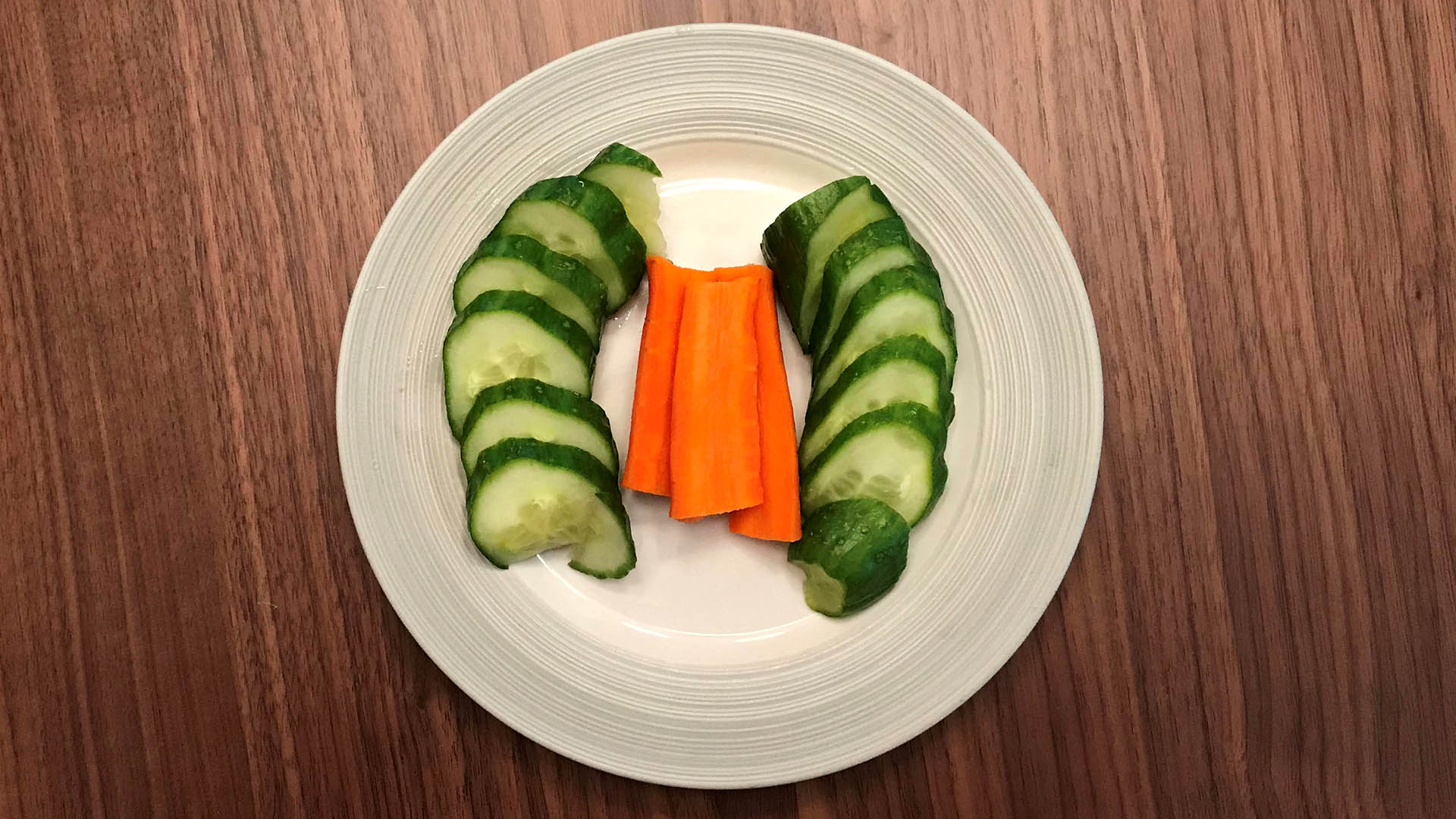

Nukazuke can be made from any vegetable, but the most common include cucumbers, carrots, daikon radishes, and eggplants. Like sourdough, home cooks can receive a nukadoko starter from a friend, or they can create one of their own. James, who has had his nukadoko for several years, received his starter from a friend in Kyoto who thinks the bran is more than 200 years old.

The cultured bran bed not only creates delicious sour pickles, but it also preserves the buried vegetables. For those of us bulk-buying food, this can be a great opportunity to free up some refrigerator space and extend the life of wilting produce. And, traditionally, early spring to early summer is the best time for preparing nukazuke; that's when vegetables become more widely available and the warmer air stimulates the growth of bacteria.

I had been curious about nukazuke pickles for years, but I never had the time to make them. Then, after the novel coronavirus sequestered me in my apartment, I found myself puttering around the kitchen looking for cost-friendly and time-consuming amusement. I decided to give nukadoko a try.

The ingredients required to create a nukadoko are either already in your pantry or easily sourced at a grocery store. Here's what you'll need to make your nukadoko bed, adapted from a recipe in Ikoku Hisamatsu's book Tsukemono: Japanese Pickling Recipes:

- 200g rice bran

- 200g filtered water or room-temperature water that has been boiled

- 26g salt (between 13-15% of the rice bran weight)

- A sealable container, like a ceramic or enameled metal pot or plastic Tupperware

- Aromatics, if desired, such as ginger, miso, seaweed, garlic, or beer

- Vegetable scraps, such as torn cabbage leaves, radish tops, and carrot skins

To start, thoroughly combine the rice bran, water, and salt in your nukadoko container. The mixture should resemble wet sand. This is probably the closest most of us will get to lying on a beach this year.

Once the base ingredients are mixed, add any aromatics you want to try. I added ginger, garlic, and seaweed, but Liss recommends incorporating sourdough crumbs and dark beer to jumpstart inoculation and create a more complex flavor.

Bury the aromatics in the bran mixture, then begin adding vegetable scraps to start the fermentation. Pat down the top to smooth the nukadoko's surface, seal the container, and store overnight in a warm, dark place.

The vegetable scraps will need to be removed and replaced with fresh ones each day; by constantly introducing new sources of lactobacillus, the rice bran will itself begin to host the bacteria. Be sure to wash your hands before handling the nukadoko. This will prevent other types of bacteria from entering the culture. Additionally, when you replace the vegetables, be sure to aerate the bran by turning it over. According to James, this helps to redistribute the enzymes, resulting in a healthy, low-pH nukadoko.

Bury new vegetable scraps each day until the nukadoko develops a slightly sour scent. This smell indicates the presence of lactic acid and should appear after a week or two.

Once your nukadoko starts smelling funky, you're ready to pickle. Thoroughly wash the vegetables and lightly rub them with a bit of salt. Bury the vegetables in the nukadoko and leave them to sit. Watery vegetables like cucumbers will take just a few hours, but heavier, more dense vegetables like turnips will take a few days. However, the time will also depend on your storage conditions. If the nukadoko is on the colder side, it'll take a while longer to pickle the vegetables.

When your pickling time is up, dig out the vegetables, rinse them with water, and enjoy. Liss says that home cooks new to nukazuke pickles will be surprised by the different flavor: "The pickles are going to be a little funkier tasting than your store-bought, salt-brined pickles."

If the nukadoko becomes too acidic, the Hisamatsu recipe recommends sprinkling mustard powder onto the bed, which will help neutralize the bran.

Once your nukadoko is sufficiently inoculated, you'll need to spend some time experimenting with various vegetables to get the pickling timing right. I have to admit, I was underwhelmed the first time I pickled vegetables in my nukadoko. But after I let the bed culture for a few more days and extended the pickling time, I produced a delightfully sour pickled carrot and cucumber.

I find the practice unexpectedly comforting. In an otherwise unsettling time, I look forward to the few moments each day where I get to squeeze wet bran through my fingers. Like my first foray into sourdough, it provides structure in days otherwise unmarked by transition.

Liss notes that this is a common experience. "It's kind of comforting to have this little pet that you have to take care of," she says. "Everything is so uncertain, but you know you have to feed this thing every day."