How To Devise The Perfect Unexpected Flavor Combination

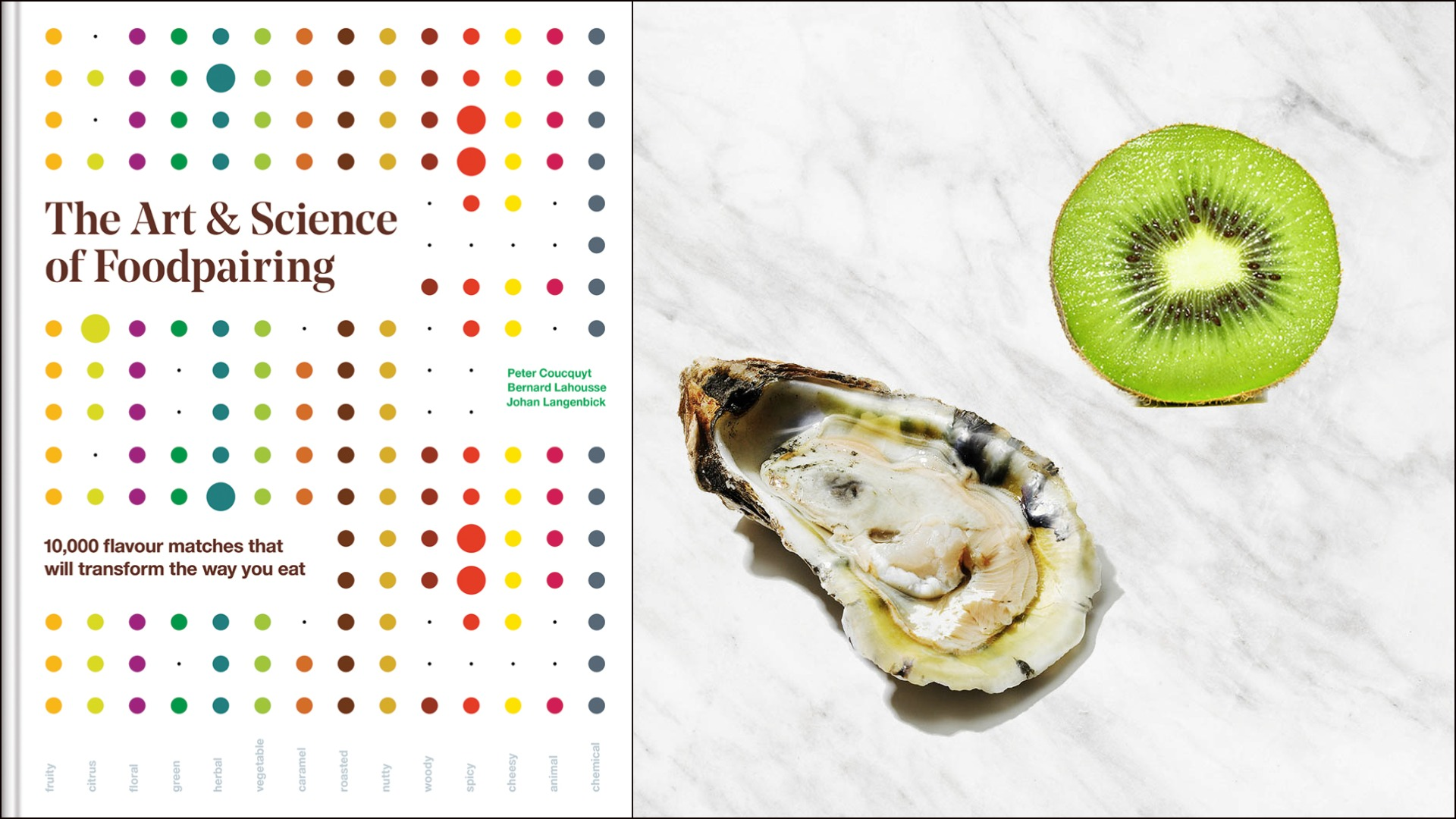

There are some flavor combinations that are undeniable classics: chocolate and peanut butter, lime and ginger, basil and tomato, pumpkin and ... spice. But think of all the flavors in the world. Why stick to the familiar well-trod path when there are new worlds to explore, new combinations to try? Why shouldn't kiwi and oysters become equally celebrated?

A new book out in October, The Art & Science Of Foodpairing by Peter Coucquyt, Bernard Lahousse, and Johan Langenbick, promises to help its readers do precisely that. Its nearly 400 pages are packed with charts and graphs that help users combine different foods to create a desired effect. For example, if you flip to "Tomato," you'll find a chart of ingredients that go well with either tomato puree or cherry tomatoes, and then several more charts for ingredients that pair well with tomatoes with ingredients that pair well with them. Everybody knows that tomatoes and olive oil go together. But what about a third ingredient? How about boiled brown crab meat for a roasted flavor or cashew nuts for some fruitiness? And maybe some dark chocolate for dessert?

At least that's how I think it works. I flipped randomly to "Beetroot," something I don't think I have ever cooked with. It pairs well with vodka, which I guess I should have known from reading about Russian food, and that in turn goes with smoked salmon, also expected. But you could also go in entirely different direction and pair the beets and vodka with dragon fruit or tangerine to emphasize their floral or citrus qualities. Has anyone ever tried a cocktail like this? How was it?

The book is an analog version of the Foodpairing website, which does the same thing, except much more quickly with a lot less flipping around. The website also shows the degree of how well certain flavors go together. Apparently roast turkey and hazelnuts are a match made in flavor heaven, which I never would have guessed, but that's serendipity for you. Lemon zest won't add much, but bacon, on the other hand...

If I sound a bit unconvinced and vague about how it all works, it's because I still don't understand the whole process. The introduction to the book tries to explain it. The basic theory is that foods that have similar aromas will taste good together. Each food is made up of a complex assortment of aroma molecules; there are 10,000 all together, but only 10 are especially relevant to the foods we eat. These molecules tend to fall into natural combinations that create distinctive smells. Flavorpairing breaks these down into 14 separate categories, ranging from fruity to caramel to woody to chemical. Each ingredient in the book has been analyzed and its aroma components have been added to a database that make it possible to see the other ingredients with which it shares the same subset of aroma molecules. As the book says, "Any ingredients that share a subset of aroma molecules will have some overlap, and therefore combine well."

The book offers no guidance about how to mix all these ingredients together. That part is up to you and depends entirely on your ability to create or adapt existing recipes. I'd imagine the best way to start would be with a salad, which is more about flavor than precision.

But it appears that cinnamon and french fries share spicy compounds. So I went to McDonald's, got an order of French fries, brought it home, and sprinkled a little bit of cinnamon on them. It was not bad. Now that I think about it, it's probably the same principle as adding a cinnamon stick to a pan of roast potatoes, which is delicious. And then I remembered that cinnamon and potatoes are a common pairing in Middle Eastern foods and felt dumb.

Next I decided to try something more daring: garlic, white toasting bread, Gruyere, and orange juice. According to the flavor chart, they all contain green and cheesy notes. A computer algorithm doesn't take into account piddly human details like sweet and savory, or breakfast foods and dinner. And no one ever became a flavor pioneer by sticking timidly to the tried and true.

So I toasted some white bread, slathered it with garlic compound butter, and laid some slices of Gruyere across the top. The combination was delicious, savory and slightly funky, but anyone who has ever enjoyed cheesy garlic bread could guess that it would be. And also, garlic, toast, and cheese are three of my favorite things in this world.

Then came the moment of truth: the orange juice.

Reader, it was not terrible! It did not make me want to vomit. The flavor was strong, and it overpowered the cheesy garlic toast at first, but afterward, when the aftertaste lingered in my mouth, it was not repulsive and it didn't make me want to run for a glass of water. I definitely tasted the cheesy elements, but I couldn't pick up on the green. (Strangely, Gruyere has a fruity flavor note, but orange juice does not.)

I'm not sure if this is a combination that chefs will be able to sell on menus, although now that I think about it, a salad with orange slices, garlic croutons, and shredded Gruyere might have a certain amount of appeal.

This book will be useful to home cooks who are bored with their usual flavor combinations and want to try experimenting. It may also be helpful to parents and anyone else who is dealing with a picky eater: as the authors write, "Associating a flavour you like with a new flavour you do not like will lead you to liking the initially unliked flavour more.... If one flavour in a new combination is liked, any other flavour in that pairing will over time become liked too."

Let the adventures begin!