How To Cook A Wolf, A WWII Cookbook, Has Plenty To Teach Modern Readers

"War is a beastly business, it is true, but one proof that we are human is our ability to learn, even from it, how better to exist. If this book, written in one wartime, still goes on helping to solve that unavoidable problem, it is worth reading again..."

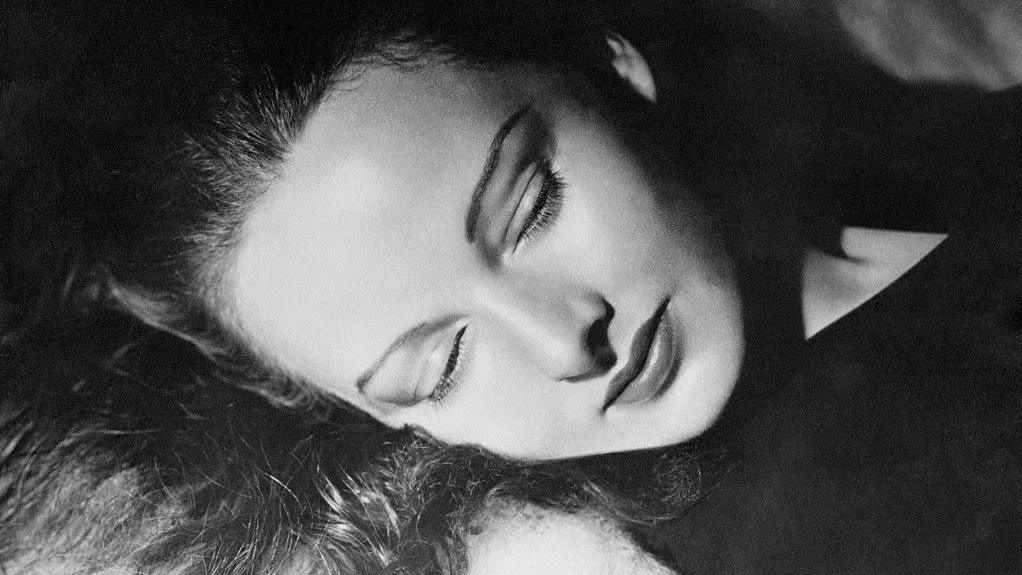

These words appear in the introduction for How To Cook A Wolf, a treatise on war that doesn't discuss politics, society, or religion. It was one of the first books written by famed 20th-century prose stylist M.F.K. Fisher, whose narrative essays launched food writing as a respected genre and paved the way for publications like this one to exist. While her most popular collections describe her development as an adventurous and well-traveled eater, her skill seems most evident to me when she writes about artless subjects like the life span of an oyster or, in this case, cooking with the pittance allotted by World War II ration cards. Originally published in 1942, How To Cook A Wolf is presented as a wartime cooking guide, but as suggested by the introduction above (which was added to the edited version Fisher released a decade after the book's original release), its essays are an argument for living the best life that you can when everything around you goes to shit. The tone and message of How To Cook A Wolf feel oddly well suited to the current moment; it was written for an audience that lived in fear of bombs dropping from the sky.

Each chapter resembles a how-to guide focusing on a particular food group, or a problem that was likely to strike home cooks during the war. My favorite is an anecdotal essay about the value of entertaining and being generous even when you have nothing, aptly titled "How to Be Cheerful Though Starving." Another, "How to Drink to the Wolf," shares a handy recipe for making flavored vodka from grain alcohol. The titular wolf refers to the metaphor of a wolf at the door, representing the threat of starvation, despair, and insecurity. Along with able-bodied men, gone was the assurance that another meal would follow the last, that a loved one would return as expected, and that you would have gas to operate your stove. Fisher believed that cooking might offer back some control and the comfort to carry on living. While the coronavirus pandemic is hardly comparable to a world war, anyone who's recently found their life upended may find that this premise still applies today.

How To Cook A Wolf is barely a cookbook, and the recipes shared therein are more conceptual than expository. Ingredients for scrambled eggs include: "8 eggs, ½ pint rich cream... or more, salt and freshly ground pepper, grated cheese, herbs, whatnot, if desired." The ellipses and suggestion that we might want more "rich" cream in our eggs is a signature M.F.K. Fisher touch. Her approach to eating and cooking was sensual and individual—a sister act to the mental masturbation of writing and reading. Describing a loaf of bread, she writes, "It was naked, like a firm-hipped woman, without benefit of metal girdlings." This sexy boule might seem odd out of context, but the description hints at an essential theme: the lust you feel devouring a juicy nectarine or holding a substantial loaf of bread ought to be embraced rather than denied. By studying our hungers, we can know ourselves, and it'll set us free from the fear and turmoil that the world might inflict on us. For Fisher, roasting a pigeon for Sunday supper was a form of introspection and the best way to assert your dignity in the face poverty and war. Pigeons are hard to come by these days, but recently I've found amidst the noise of social media and our discordant national reckoning with racial injustice, there is still quiet in rolling out pie dough, and sufficient solace to study my own place within a flawed system.

Though she advocated for cooking, there are points in How To Cook A Wolf when M.F.K. Fisher expresses frustration toward the canon of home economics (written by and for silly women) in which her writing was placed. Mocking the beauty regimens recommended in old cookbooks, she writes:

But when the belles grew less so, and their hair a little thin at the sides of the pompadours, did they really rub their scalps with onion juice several times a week? Did they (could they?) put gasoline liberally on their heads daily and coconut oil three times a week, if their gilded tresses finally began to fall in earnest? Or did they retire to their boudoirs, read a hint entitled, starkly, Nervous Breakdown, and proceed to develop all its carefully detailed phenomena?

She similarly ridicules the magazines of the era for their "breathless" excitement for money-saving hacks. It's not that she thinks the information is totally useless. Rather, that no one has ever saved money by blindly following the advice of advertisement-driven magazine copy. Her voice is reassuring, even if it's not explicitly helpful. The encouragement to rely on your own common sense is more valuable than a tip for buying cheap cuts of meat, or whatever suggestion recently led Americans in 2020 to spend their grocery budgets on yearlong supplies of paper products.

Fisher gives more concrete suggestions in a later chapter about preparing for air raids ("How Not to Be an Earthworm"). She succinctly writes, "Blackouts happen at night, of course, and so, usually does dinner." Her advice centers on which rooms to black out, securing a way to cook food when the gas is shut off, and which preserved foods (and booze) to keep on your blackout shelf. Closing the chapter, she adds some prescient guidance, saying that in an emergency,

No book on earth can help you, but only your inborn sense of caution and balance and protection: the same things cats feel sometimes, or birds, or elephants. Everything resolves itself into a feeling that you will survive if you are meant to survive, and every cell in your body believes that.

Once again, this isn't really helpful, but it is somehow reassuring, if only because it seems true.

Though How To Cook A Wolf is not a memoir, its focus on war and survival mean that the rough bits of Fisher's life seem to hang like a specter in the background, informing the prose. I feel required to mention to any future readers that this book was written months after Fisher woke one morning to find that her husband had killed himself outside the house they'd recently purchased together. He was chronically ill, and neither his illness nor his death are mentioned directly in the text, which is wholeheartedly focused on cooking. A sentence in Joan Reardon's biography (Poet of the Appetites: The Lives and Loves of M.F.K. Fisher) mentions that in the time after her husband's death, Fisher herself considered suicide. Instead, piling bills and the events of Pearl Harbor inspired her to write a book about how best to survive war, in turn penning her own survival.

The dark humor dappling the book suits a widow in her early thirties. In one example, Fisher finishes a straightforward chapter on cooking poultry with an excerpt from a 1660s cookbook that explains how to cook a living goose and eat the thing before it dies. Many of the other funny bits were added when How To Cook A Wolf was republished nine years later. Rather than editing her words, Fisher revised the book with bracketed comments mocking her younger self, pointing out grammatical errors, and offering improvements for recipes. It's this revision that makes How To Cook A Wolf timeless. Remarkably, she added a section of impractical recipes, instructing, "Close your eyes to the headlines and your ears to the sirens and the threatenings of high explosives, and read instead the sweet nostalgic measures of these recipes, impossible yet fond." This suggests the book was never just a functional guide for housewives confronting World War II. What remained useful nine years after its publication, and still today, was the witty, resilient, and sympathetic sisterly voice admitting to readers that everything would not be okay, but the power to make bread, roast meat, and share with others might allow us to carry on anyway. Whatever shape the wolf at your door takes—unemployment, food shortages, property damage, sickness, grief, powerlessness in an unequal world—here's a book to help you cook it.