What The Hell Is Jell-O?

I know what you all are thinking, and the answer is no, Jell-O is not made from horses' hooves. Any more questions?

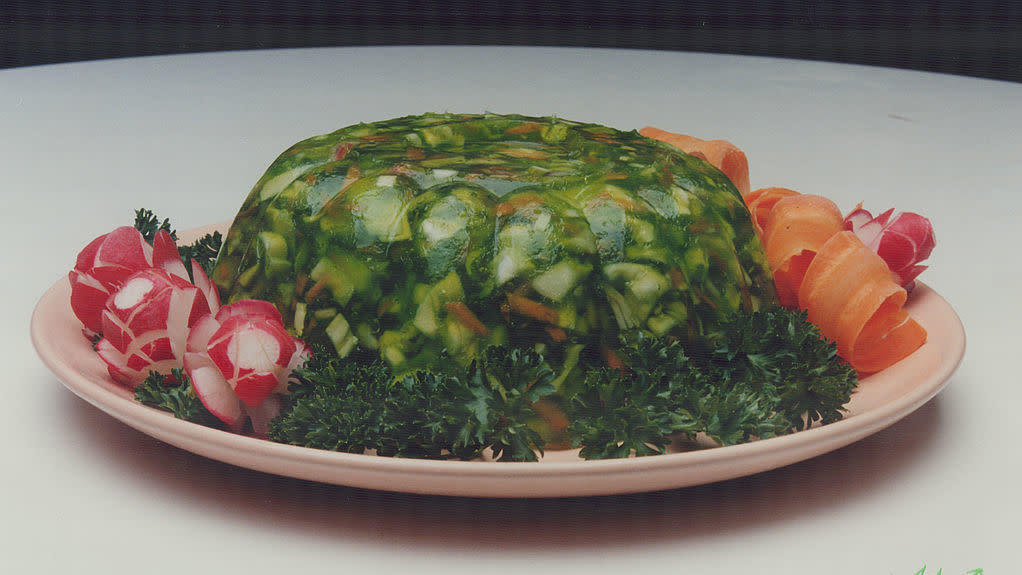

Okay, fine. It is my sad duty to inform you that Jell-O is indeed made from gelatin, which is itself made other parts of horses—primarily bones and hides—and also pigs and cows. This process goes back to medieval France when cooks first began boiling leftover animal parts (including bones) to extract extra flavor to make stock. They discovered that when stock cooled, it turned into jelly, which was sort of neat. (The first recorded—or at least surviving—recipe appears in a manuscript called Le Viandier that was produced around 1375.) As these cooks grew more ambitious, they discovered that if they beat egg whites into cold stock and then heated it to a simmer, the egg whites attracted all the impurities in the stock and brought them to the surface so that they could be skimmed off. The result, when it cooled, was a clear, quivering block of meat jelly that they called gelée, and they discovered it could be a wonderful canvas for suspending and displaying other kinds of foods. (This presentation was called an aspic.) Why did they do this? For the same reason we spend precious hours whipping instant coffee. A version of Instagram has always existed in the human mind.

Later on, chemistry caught up with cooking to explain why this particular reaction happens. Mammal bones, tendons, and cartilage are all made of the same protein, collagen. When collagen is subjected to heat and water, its structure breaks down and rearranges itself into gelatin.

Hooves aren't used to produce gelatin because they're not made of collagen, but another protein called keratin. Keratin also forms horns, talons, and, in humans, nails. Animal feet, however, are a great source of collagen: think of your own foot and all the bones and tendons in there. (And yes, human proteins have also been used to produce gelatin. For science.)

For a long time, gelatin was eaten mostly by rich people, who had servants to perform the long and laborious process of extracting and clarifying gelatin. In the 19th century, however, people began inventing and patenting quicker ways to turn collagen into gelatin with chemicals and steam power, and then to cool it and extrude it into sheets so that home cooks could prepare quivering masses without having to go to the trouble of all that boiling. This was exciting! Now middle-class people could eat aspics, too. The French government was so excited that it actually considered using meat jelly as a cheap source of protein for The Poor. It's not recorded whether anyone actually said, "Let them eat gelée."

Working with gelatin sheets, or leaves, was still a fidgety process. The sheets had to be soaked in cold water for several minutes and wrung out before you could add them to the food, and you had to be careful about making sure the gelatin was evenly dispersed. In 1889, Charles Knox figured out a way to produce powdered gelatin, which, in theory, was faster and easier to work with: all you had to do was let it bloom in cold water, and then you could add it to whatever you were making and it would distribute itself evenly. Sheet purists claim that powdered gelatin produces a cloudier final product, but the two are essentially interchangeable, although how many sheets equal a packet of powdered gelatin remains a subject of great controversy.

It would take a pair of true visionaries, though, to see the potential of gelatin as dessert, especially for people who lacked ovens or the patience (and arm muscles, in the days before KitchenAid mixers) to beat eggs and butter into cakes. Those visionaries were the husband-and-wife team of Perle and May Waite, who, in 1897, came up with the genius idea of combining gelatin powder, sugar, and artificial flavoring into a simple one-packet dessert, which they called Jell-O. Two years later, they sold the trademark to the Genessee Pure Food Company for $450.

Both Knox and Jell-O spread the gospel of jiggly salads and desserts via free cookbooks that contained wild assortments of recipes that proved that there are no limits to the culinary imagination. (Just check out this list of Jell-O flavors.) Which, when you consider that gelatin started with people boiling bones in water and getting excited when they discovered that the result, when it cooled, turned into jelly—well, it seems a fitting legacy.