Herring Is The Cheap, Healthy Fish Most Americans Are Overlooking

Unless you were specifically seeking it out, you've probably never noticed the little jars on grocery store shelves stuffed with scaly skin-on fish floating in sour cream, or a wine sauce the color of a murky creek. Or maybe it caught your eye and it made you shudder. For those accustomed to fish only in stick form, herring can be a daunting species. Growing up with a Norwegian mother, I feasted on these little fish for as long as I can remember: pickled herring, mackerel filets packed into little tins with tomato sauce, dried whitefish soaked in lye. Herring, consigned to the ethnic aisle at most American grocers, remains king in many parts of the world.

Herring has held special significance in Scandinavia for centuries. Neolithic-era Scandinavian burial mounds contain herring bones. In the Middle Ages, fisheries in the Baltic and North Seas burst with herring, which remained a cheap and common fish on the market for centuries to follow. Hendrikje Van Andel-Schipper, a Dutch woman who died at age 115 in 2005, attributed her long life to eating herring every day. Though once wildly abundant in waters off Norway's coast, fresh herring has declined since the mid-20th century. Still, herring remains a strong Nordic tradition and is also found in cuisines all over the world.

Scandinavia isn't the only place with a robust herring culture. Other parts of Europe enjoy herring in a smattering of ways, and smoked variations of the fish are also popular in parts of Asia. In the Caribbean, smoked herring is fried or sautéed; cooked with onions, garlic, hot peppers, and tomatoes; and served over rice or with roti. As with the herring in curried cream sauce, this way of preparing herring adds a rich layer of spice.

Versatile, cheap—have we mentioned it's healthy, too, rich in omega-3 fatty acids? And that it's relatively free from harmful contaminants, as it's near the bottom of the food chain, and not subjected to overfishing?

No, I'm not a front for Big Herring, I'm just an enthusiast who enjoys inexpensive food that's good for you and actually delicious. But I can understand that, for many, it's a challenge to eat something that looks vaguely like science fiction. So allow me to reach out with a warm, friendly hand, and guide you—one step at a time—on a journey through the land of herring.

Beginner level: Pickled herring in wine sauce

If you're new to herring, start here. Pickled herring typically undergoes a two-step curing process that involves extracting excess moisture with salt, then pickling the fish in a mixture of vinegar, onions, peppercorn, bay leaves, and other spices. This method is one of my favorite ways to enjoy the fish, because the brininess of the vinegar cuts through the fish's natural oiliness. Pickled herring is usually served with a variety of sauces, and it's good on its own or on a slice of rye bread or crispbread. This variation has a subtle sweetness to it, balanced with strong onion flavors. (Sometimes I like to add more red onions to amplify its onion-ness.) I've found it pairs well with a simple potato dish, too.

Intermediate level: Pickled herring in cream sauce

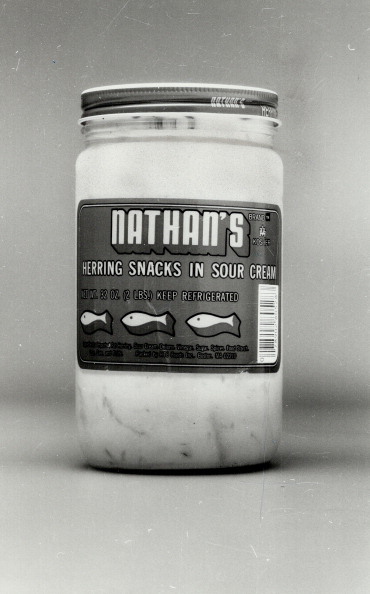

Once you're accustomed to pickled herring, you can graduate to the cream-sauced variety. Sometimes referred to as "creamed herring," this style combines pickled herring with a thick sour cream sauce that blends a subtle sweetness with acidity—a sweet and sour fish, if you will. Dill and sweet onions are combined with sour cream, sometimes with mustard. The Vita brand of jarred herring offers an entry-level creamed herring and can be found in most American grocery stores. It's typically enjoyed with the same simple accoutrements as the wine-sauce variation. I grew up eating herring in wine and cream sauces but was recently introduced to Karrysild, a Danish take on pickled herring that's served in a yellow curried cream sauce. The simple addition of curry powder to a basic cream sauce adds a new layer to creamed herring.

Advanced level: Smoked herring

With pickled and creamed, whatever fishiness that lingers in herring is masked. Here, we experience herring au naturel. I prefer smoked herring—salted then smoked over wood chips—on its own as part of a cheese and charcuterie plate or in a simple dill sauce. As with pickled herring, it's often served with potatoes in northern Europe.

In the United Kingdom, kippers—whole herrings split butterfly-style then cold-smoked—are enjoyed for breakfast, but also make for a convenient and savory midday snack. Most American grocers stock this alongside the canned tuna (the ones sold in green tins at Trader Joe's are reliably delicious).

Pro level: Sour/fermented herring

With an even bolder flavor, surströmming, or sour herring, is pickled herring on steroids. Sour herring is made from Baltic herring, a small-sized subspecies caught in the brackish waters of the Baltic Sea. Sour herring undergoes a fermentation process of at least six months, during which just enough salt is used to prevent actual rotting. Sour herring has its roots in northern Sweden, where it has been consumed since at least the 16th century.

The lengthy fermentation process makes for the smelliest iteration of tinned herring. According to Sweden's own official government website, sour herring "has a strong, pungent smell of rotting fish" and "should be opened outdoors." Because of its intense flavor, it's usually coupled with a food more decidedly bland, such as a simple buttered slice of bread or boiled potatoes. I have tried it exactly once, and while I didn't hate it (a layered, nuanced, piquant flavor), that aroma is difficult to overcome, making sour herring one of the more impenetrable variations on the fish. But to truly graduate herring academy with honors, you must check it off your list. I promise, it tastes better than it smells.