Free School Lunch Is About More Than Money

My high school meals provided an experience I only fully appreciated years later.

In high school, it never occurred to me that school lunch had a cost. Many days, my friends and I simply waltzed through the cafeteria's lunch line without so much as a sneeze or a dollar expelled.

My family had immigrated to Oregon when I was ten years old. For years, we hovered below the federal poverty line, a fact that I was painfully aware of but did not fully understand. Our two-bedroom, '70s-style apartment sat next to one of the busiest streets in Portland: 82nd Avenue, known to many in town as an "Asian hub" due to its many Asian-owned establishments, from Chinese herbalists to grocery stores to Vietnamese restaurants.

While middle school was uneventful, high school proved to be a different experience altogether. It was there I met my best friend, Olga, a Russian girl with five brothers and a similar background to mine; I also befriended seven Vietnamese girls to whom I would remain close throughout my high school years. For all of us, the cafeteria was an epicenter of social interaction.

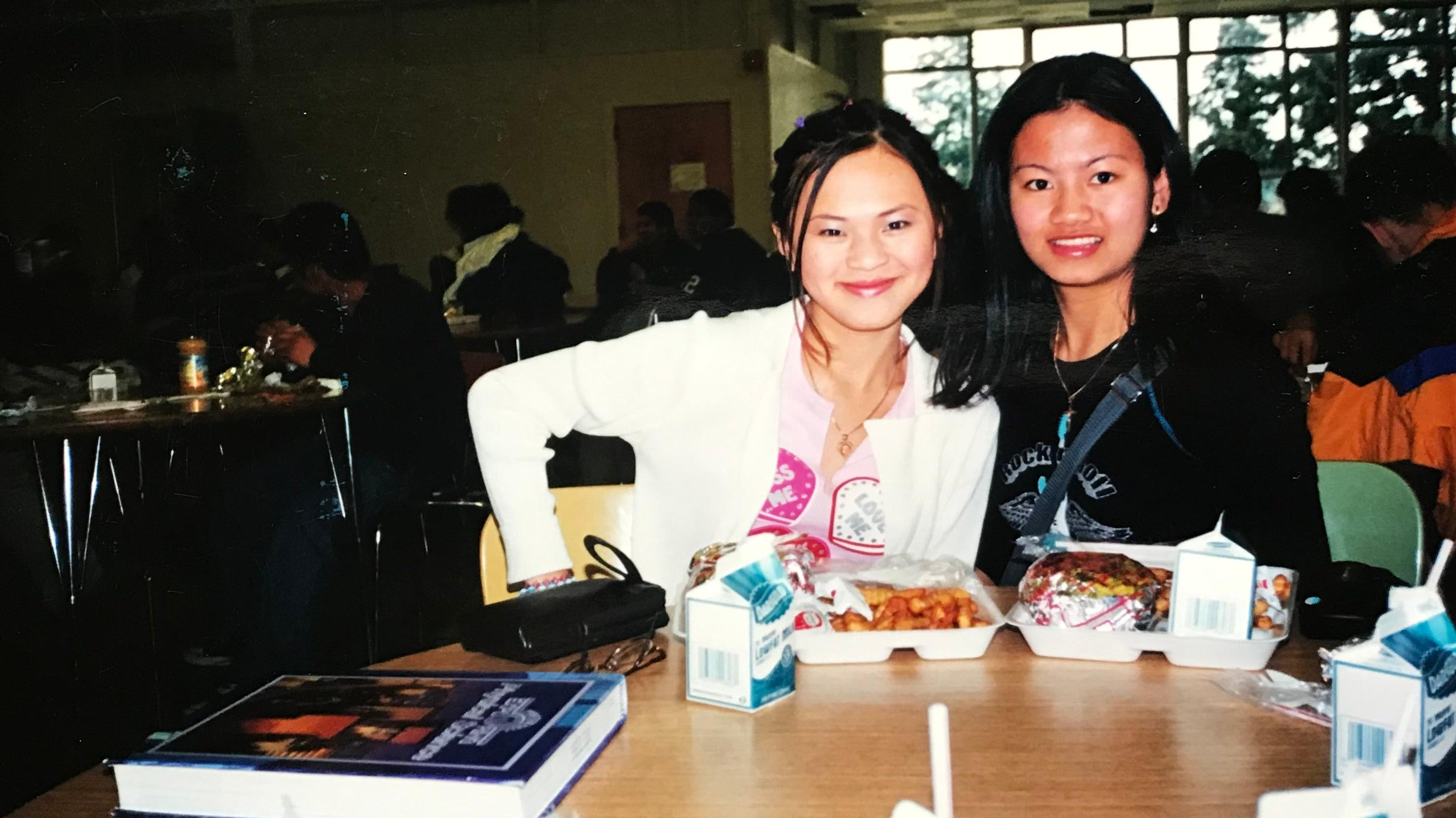

High school lunches in the early 2000s

It was only years after graduating that I realized my friends and I never paid for lunch because we were the recipients of the free and reduced lunch program created under President Harry S. Truman in 1946.

It's a program that has certainly helped countless struggling families, alleviating a source of financial stress for parents and children alike. Still, the lunch program is laden with psychological implications, instilling in students an awareness of both income and inequality. It's something that University of North Carolina psychologist Keith Payne experienced back when he was in elementary school.

On an episode of the Hidden Brain podcast earlier this year, Payne recalled an experience in fourth grade when a new lunch lady demanded that he pay for his lunch. Because he never had to pay before, he was flummoxed and embarrassed.

"And so, that awkward moment standing in the lunch line suddenly increased my awareness of not only the inequality in my classroom, but the implications of what it meant to be one of the poor kids," he said.

It doesn't have to be this way—and my friends and I are proof.

The social benefits of school lunches

In my high school's gray-walled, linoleum-floored cafeteria, Olga and I would sit at one of the round tables, chatting about anything and everything. The food wasn't exactly stellar—there were lots of chicken nuggets and tater tots during those days—so we often left half of our lunch plates uneaten.

Meanwhile, across the room, my Vietnamese friends sat at their own table. Sometimes I'd join them; other times, it was just Olga and me. (Somehow it never occurred to me that I could bring my Russian friend over to my Asian friends so we could all sit together.) Around us was a cacophony of cafeteria chatter, everyone having their own conversations: cheerleaders, athletes, school nerds, art geeks, and music maniacs.

On warm days, we'd step out onto the courtyard and sit at a picnic table. Sometimes we'd skip the free lunch in favor of the McDonald's across the street, but those trips were few and far between, as neither of us ever had an allowance. Like many high school girls, we'd stare awkwardly at popular boys, hoping for a glance back.

Looking back on it now, I realize that by eating the same foods as one another day in, day out, in the comfort of a courtyard no bigger than a garden, we were forming an even stronger social bond. Through mouthfuls of fries and nuggets, we learned more about each other than we ever thought we would, and those lunch hours are what stand out among my fondest high school memories. We were never made to feel inferior by what was on our plates, because it was the food on so many students' plates. It was, more than anything, normal. At their best, those school-subsidized lunches provide a shared social experience, and that's a benefit we don't talk about nearly enough.