In Praise Of Edna Lewis' In Pursuit Of Flavor, an Essential American Cookbook

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

Paul Fehribach is the chef/owner of Chicago's Big Jones, and a member of the Board of Trustees for the Edna Lewis Foundation, an organization founded to preserve African-American food culture.

In the summer of 2008, I found myself in the deepest funk of my relatively young life. My first restaurant, Big Jones, had opened a few months earlier to generally very good but naggingly mixed reviews. The afterglow of the opening weeks had faded, and with it the honeymoon of booming business that comes with a new restaurant opening in Chicago. The economy was quaking, the yield curve was inverted, and I expected the mother of all recessions to hit us over the head soon. All of the optimism and confidence required to open a small restaurant evaporated, and I was consumed with an existential dread that my dream restaurant was doomed.

The worst part of it is that I wasn't having any fun. Cooking became a game of whack-a-mole, chasing perceived trends and hot ingredients and new techniques to find an elusive formula that would transform my restaurant's fortunes in the face of strong headwinds. I was lost, and I knew it. It was a precarious spot for a months-old restaurant, and the anxiety and depression I thought I'd beat as a twenty-something were back with a vengeance.

Then, as if by divine messenger, a young couple struck up a conversation with me after their dinner on a Saturday night. We talked about the South, inspiration, and how it seemed Southern cuisine might be coming into its moment. They asked if I'd read any Edna Lewis. "Who?" I asked. I swore I'd done my homework: I'd read Bill Neal, Nathalie Dupree, Hoppin' John Taylor, Paul Prudhomme, the Lee Brothers, and at least I thought, all the others culinary figures who mattered. They said they liked the restaurant, but were insistent that Edna Lewis had the goods I needed to take it to the next level. Oh, was that an understatement.

Edna Lewis, inarguably, helped shape Southern cookery. Born in Virginia in 1916, Lewis first garnered acclaimed in the 1940s as owner and chef of a restaurant in Manhattan called Cafe Nicholson. Consider the time: Lewis was a black female head chef, and needless to say, back then it was more the exception than the rule. But where she was most influential was in her cookbooks, of which she authored four during her lifetime (Lewis died in 2006 at age 89).

Inspired by that young couple, I bought my first Edna Lewis cookbook, The Taste of Country Cooking (which was actually her second book). I was most curious to read the foreword by Alice Waters, who cited Miss Lewis (as she was universally called) as an important influence, if somewhat surreptitiously. As I read through the first pages of the book, I felt a peace that had left me years before, and I read the entire book in one day. The quiet confidence exhibited in Lewis' cuisine—which was always simple on the surface but informed by keen foraging, shopping and precise technique—reminded me first of what drew me to Southern cuisine in the first place. She had that proud sense of place and a tireless drive to eat well. But more importantly, she showed me that my own roots in rural American farming culture and my own ardency in seeking those flavors I remembered from the woods, the waters, and the garden—those were my true strengths. They were inside me the whole time, lying dormant, waiting for someone like Miss Lewis to awaken. I had lost myself when I hid them to pursue fickle restaurant trends.

There was more reading to do, and I found The Edna Lewis Cookbook, her seminal treatise, in which she sang the virtues of pure and fresh ingredients and seasonal cooking. This was 1972, when even Chez Panisse was still mining old continental cookbooks and California Cuisine wasn't even on the radar. I was beginning to realize that even in modern Chicago, you don't need a pantry of hydrocolloids and a nitrogen tank to make compelling food, and that in fact, my path would have to be my own.

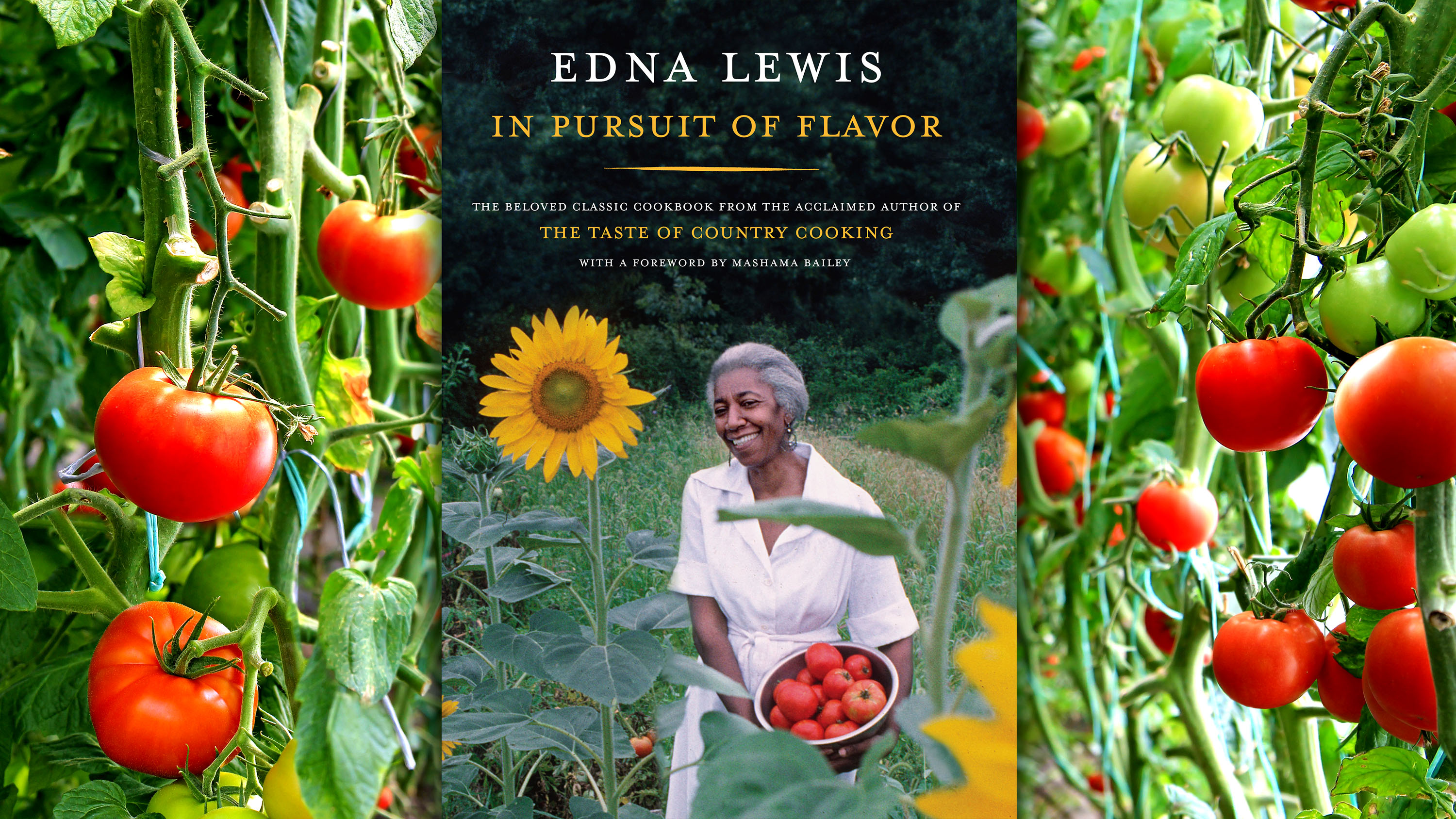

Perhaps my favorite Edna Lewis Cookbook is In Pursuit of Flavor, first published in 1988 and republished this week in a handsome hardcover from Alfred A. Knopf. Consider the culinary scene from 30 years ago: California Cuisine was causing an earthquake in American culinary culture and Paul Prudhomme was transforming our perceptions of Creole Cuisine. Meanwhile, Edna Lewis was at least a decade ahead of the curve. She anticipated the heirloom crop and heritage breed livestock revival, calling on her readers to seek out Kirby cucumbers for pickles, Kieffer pears for canning, Kentucky Wonder beans, Black-Seeded Stimpson lettuce, eggs from Barred Rock and Rhode Island Red chickens, on down through the pantry and larder.

Lewis opens the book with a description of the local foodways in Freetown, Virginia where she grew up, and how she learned about flavor from the daily act of procuring and preparing food. To a country boy like me, she became a lifeline to my own identity as a person who was raised on food we hunted, fished, or grew ourselves or traded with people we knew. Her simple-on-the-surface approach had me smitten, but what kept me hooked was her combination of flawless technique and the fact she clearly understood flavor in a way few chefs do.

In Pursuit of Flavor is arguably Edna Lewis' most important book, as it most expansively lays out her approach to cooking with well over 100 recipes spanning more than 300 pages. Her pursuit of flavor expounds upon chapters on preserves, vegetables and fruits, fish and seafood, poultry and meats, baking, and sweets. She explains why she doesn't eat much beef, and then, presents the reader with recipes for every part of the pig, guinea fowl, rabbits, ducks, wild turkey, pheasant, even the optional squirrel. There are gooseberries, currants, damson plums, boysenberries, wild persimmons, chestnuts, black walnuts, and a special call out for one of my favorites, Winesap apples.

She not only demonstrates scholarly knowledge of the culinary applications for such ingredients, but also talks through the recipes in clear, concise language to make them easy for you to reproduce. She explains when and where to look for items like wild watercress and black walnuts, and how to handle and store them for optimal flavor—because flavor, after all, is what she's pursuing. In short order, Edna Lewis became the most influential chef in my life, and while I haven't used many of her recipes directly from the page, one particularly successful influence was when I merged her fried chicken brining and frying method with my dredge recipe, and one of the most acclaimed fried chicken dishes in America was born.

More importantly, cooking from my own deeply ingrained instincts as Miss Lewis did, I found my confidence. I started to have fun cooking again. It was a life preserver, pulling me out of the funk. Eleven years later, Big Jones is still here and better than ever, a testimonial to the power of Edna Lewis' influence and the perennial importance of books like In Pursuit of Flavor.