Point/counterpoint: Is Matzo Any Good?

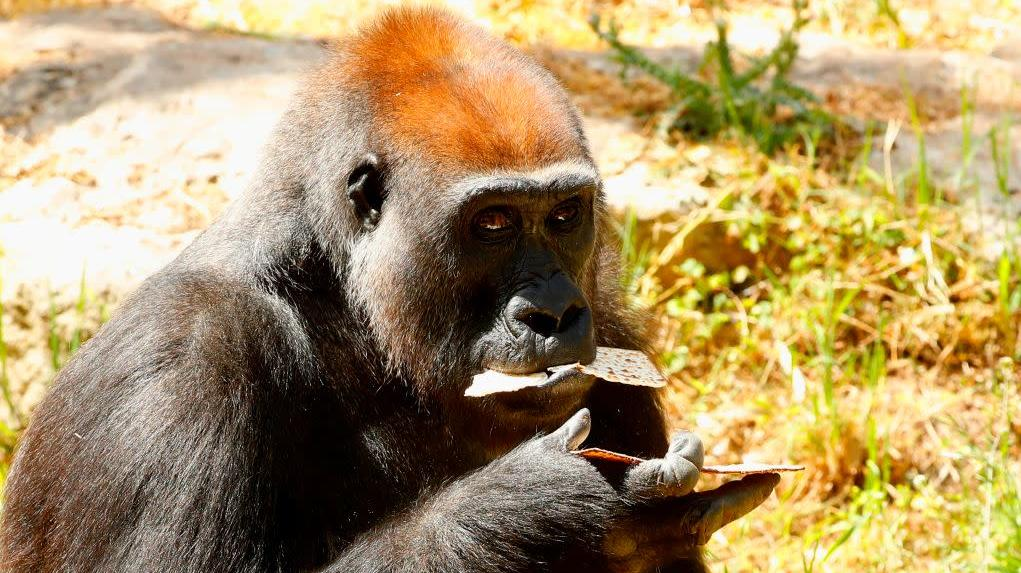

We are now right in the middle of Passover, the Jewish holiday that commemorates the Exodus from Egypt and, as a reminder of that great event, requires all celebrants to forego leavened bread for matzo for eight days. Some members of the Takeout staff think this is a real hardship. Others think they should stop complaining because matzo is delicious.

by Aimee Levitt

Matzo makes its first appearance about a quarter into the Passover seder during the Four Questions, asked by the youngest member present. The very first question is, "On all other nights, we eat either bread or matzo. On this night we eat only matzo. Why?"

This question, like the other three questions, is completely contrived because on no other nights do Jews eat matzo when they could have real bread. Bread is the stuff of life. It has a variety of textures—the crispy crust, the spongy interior—and when it's warm and spread with salted butter, there is nothing better. Matzo is none of these things. It looks like cardboard. It tastes like cardboard. If you try to spread butter on it, it shatters and you get little matzo shards all over the place.

Matzo is the bread of affliction. We state it flat out later on in the seder, during the part where we talk about the various symbolic foods on the seder plate. The leader holds up a piece of matzo and says, "This is the bread of affliction." You can't get much more definitive than that.

Why are we stuck eating this crap? We do it because the order to leave Egypt came so abruptly, the bread didn't have time to rise. (For some reason, they had time to bake it though. How lucky for us! We could have eight days of eating raw dough instead.) Matzo is supposed to remind us of freedom and liberation.

Which is great. It's kind of fun to eat it at the seder. It's a festive meal: under the influence of four cups of wine, matzo seems almost benign. "Hello, old friend," you think. "It's been a while." It's even fun on the second and third day.

But then, like everything else you eat a lot of, it starts to get boring. You get annoyed with the dryness. You get tired of disguising it with lots of butter and salt or soaking it and frying it up for breakfast. You get especially tired of the all-pervasiveness: the commandment isn't just to avoid leavened bread, but anything else that's leavened or may be leavened. So in addition to matzo, that means dry cakes, rubbery macaroons, and weird-tasting potato chips. But you have to keep eating it for the whole eight days! No excuses, no respite. Your ancestors made a promise to God. This is your part of the deal, even when there's no joy in obligation, only constipation. Everything has a price. To live is to suffer.

Last week my colleague Allison Robicelli very magnanimously tried to make me see that matzo could be delicious and invented a new recipe for chicken thighs with schmaltzy matzo crumbles. I truly appreciate the effort. Nonetheless, that is just one meal out of the 24 during Passover week—two if there are leftovers. Also, the same day she delivered that recipe, she also shared with her colleagues a photo of a freshly baked banana upside down cake that looked really delicious and 100% unkosher for Passover. If you can still eat banana upside down cake along with your matzo and anything else you damned please, you're not getting the full matzo experience. You're just a tourist through the world of Jewish suffering.

by Allison Robicelli

First, let me say that I was making banana cake because it's my job. Some people are in the service of god, and I am in the service of The Takeout's readers. Before publishing a recipe, each one needs to be made (and eaten) multiple times before I decide they're good enough to go to print, so really, my life is all about hard work and sacrifice. And let us not forget, Aimee, which one of us ate all those Hot Pockets for the greater good.

Matzo is essentially a giant cracker. As a Catholic, I can appreciate a good cracker full of symbolism. When Aimee eats matzo, she's honoring her ancestors who roamed the desert for forty years, never forgetting who they were or what they believed in. Meanwhile, I grew up eating Communion wafers, the literal body of a man whose love I need to work hard every day to deserve. Those wafers are not nearly as tasty as matzo, and we had to eat them weekly, 52 weeks a year. Never go in against a Sicilian when death is on the line, and never go against a Sicilian Catholic in a suffering competition. We can take it, and we bring it.

But now, to the merits of matzo! If you're going to eat it plain, then of course you're going to eventually turn against it. Crackers are made to be vessels for other things: I love matzo with butter and salt, because it's an acceptable way to eat a few tablespoons of butter and salt without it feeling too much shame (reminder: everything is shameful). Toast it in schmaltz, like I did in this chicken thigh dish. Turn it into matzo toffee. Use it in place of pasta for lasagna—matzo fits perfectly in a 9x9 baking dish, so if you've ever got the craving for weeknight lasagna, a box of matzo will easily cut your cooking time in half. Make matzo brei! I make that all year round, both sweet and savory, and there's no end to the ways you can turn that into the breakfast of champions.

This argument does not end with a compromise, but with a death blow: Without matzo, there would be no matzo ball soup, which is the greatest of all the soups. It has all the healing, potentially life-saving qualities of Jewish penicillin, but with balls. End of discussion.