Left In The Dark: What Happens When You Dine In A Pitch-Black Restaurant

In Paris's 4th arrondissement, two blocks from architectural oddity the Centre Pompidou (which wears its insides out), is the restaurant Dans Le Noir, a similarly strange establishment that houses an abyss. The concept eatery, with multiple locations worldwide, serves patrons in a pitch-black dining area.

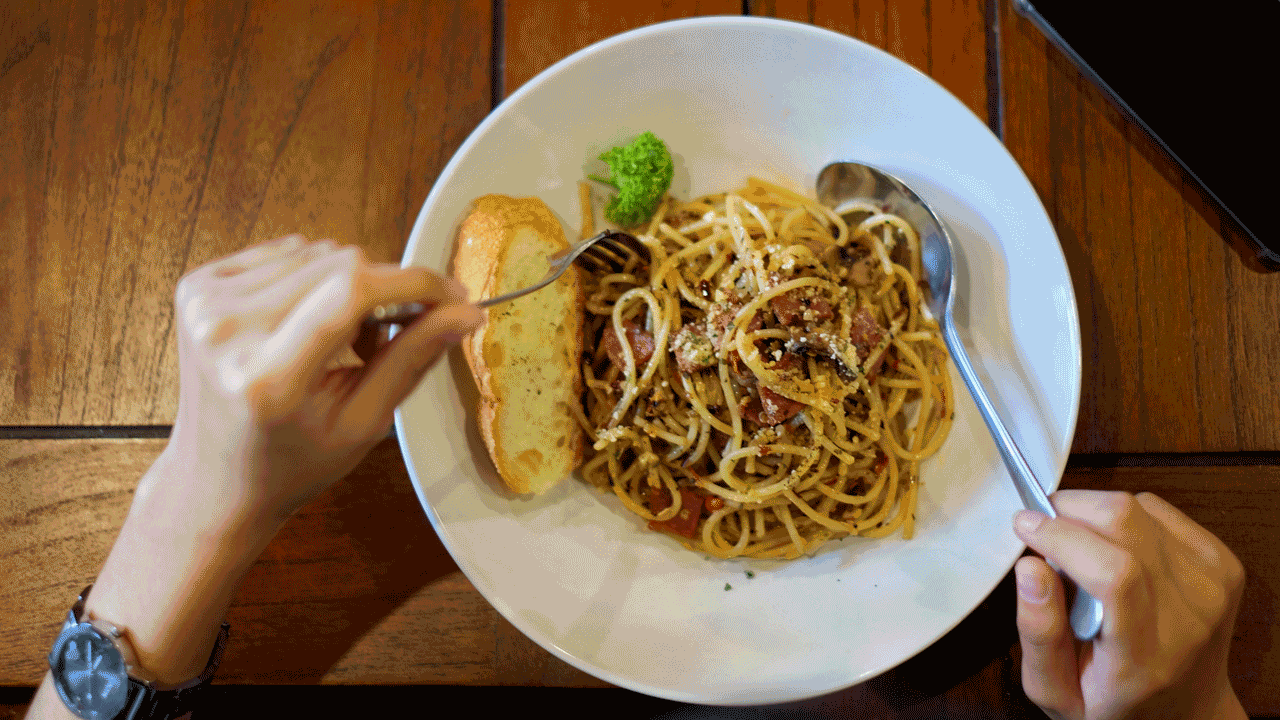

The supposed draw of such a meal is a heightened sensory experience. With no light to judge what's plated before you, you're expected to sharpen your sense of taste, touch, and smell to identify what's for dinner.

Eating in the dark isn't alien to the human condition. It's just that when it happens, it's generally to disguise ingredients rather than showcase them. Sailors during the time of Columbus would sometimes consume their ration of hardtack below deck so as not to view the maggots crawling in the brick-like bread. And stuffing your face while watching Netflix with dimmed lights is a great way to avoid counting calories too closely.

I doubt the grub Dans Le Noir Paris is serving up contains, well, grubs or anything similar. (They are already pushing people to limit with the blacked-out banquet hall.) But befitting a restaurant that keeps you in the dark, guests don't know exactly what they're getting when they ordered. Menu selections are limited to quantity. The host asks about food allergies, but that's the only info you receive regarding what you're about to put in your mouth.

The restaurant's front room is a lighted holding pen of sorts. Offside lockers are for phones, bags, watches, cigarette lighters, and anything else that can produce light or needs safekeeping. Then a bartender mixes a pre-dinner cocktail. Sipping the drink, a diner can enjoy the lounge music, or take in the classic picture frame lineup of celebrities who have also dined in the dark, such as tennis star Novak Djokovic, British royals William and Kate, and Katy Perry.

Patrons line-up conga-style, one hand cupping the shoulder of the person in front of them. Servers head up the line. All of the waitstaff at Dans Le Noir are visually impaired, putting them at an advantage after they push aside the curtains that lead to the lightless seating area.

My eyelids flick open as we wind toward the table. It's pointless. There are voices all around me, but the room is enveloped in total darkness. I can't see anything, but with my servers' guidance, I glide my legs between the table and chair. For the first time, I realize how scary this is. The shadows are suffocating. It's not that I need to see the room; it's that I can't easily leave. There are no cracks of light indicating a door might be close by. There's no way to make a break for it without upsetting a lot of people and probably injuring myself.

I start grasping in my immediate vicinity, trying to make sense of the world around me. I feel a large wall at my back. To my immediate left is the corner of the table. Beyond it is a group of people speaking softly in French. Now I'm not just isolated by blindness, but also by a language barrier.

My husband is to my right. Next to him are two middle-aged women from New Zealand. They seem as eager to connect with Anglophones as we are, so we strike up a conversation. It turns out that one is a foodie, and because it's her birthday, the other splurged on a ticket for them both. Adventurous eaters like them have flocked to the Paris establishment for more than a decade, but the pair could have skipped the international trip altogether and went to Auckland, where a local franchise exists.

Other Dans Le Noir establishments have existed in London, Barcelona, St. Petersburg, and Nairobi. A U.S. Dans Le Noir location operated briefly in New York in 2012, but has since closed. My kiwi compatriots wager a guess that it's because we Yanks are litigation-happy. I'm not sure if that's the exact reason, but it's telling that the Eater review of the New York experience includes a photo of the huge waiver guests were required to sign. We did not receive one in Paris.

Our server returns with a pitcher of water. She delegates filling the glasses to each of us at the table. We're supposed to feel around for our cup, stick a finger inside it, and pour water until our fingers are wet. We also need to keep our water glass separate from the drink we came in with and the wine pairing served with each course. It's at this point I realize this is not the kind of meal you want to dress up for. I will knock over a wine glass by evening's end, but thankfully it's one I've already drained. I also lose track of my water glass early on and end up sharing a cup with my husband.

Appetizers arrive, and the game's afoot. Feeling the food in front of me, I touch a balled-up crispy texture, like fried bread. I pop the mystery food into my mouth and taste meat. The experience recalls eating a crab rangoon, so that's what I guess it is. My husband is quick to point out there's nothing creamy inside the fried dough, though. It's also served on a bed of what is unmistakably arugula, which would be a departure from any crab rangoon I've ever eaten. Later, I learn that this was really crusty goat cheese with smoked duck breast served on arugula salad. So I got the greens right.

The starter is just as hazy. I can make out individual ingredients, but not a composite profile. There's a mild tasting fleshy slab that I take to be fish, infused with vegetal flavors. A strong hint of anise suggests fennel; the watery, crunchy rings can only be cucumbers; and the hard, waxy bumps are reminiscent of pine nuts. But there's also some stuff I can't identify, and as to putting a name to what I'm eating, I'm lost. Turns out it's sea bass ceviche with mango, cucumbers, pine nuts, fennel, and avocado carpaccio. Whatever, it tastes good.

By the second main, I've abandoned the whole dinner detective act. It tastes like red meat and potatoes, but the seasonings are lost on me. Eventually, I find out that I'm actually eating angus beef with chanterelle mushrooms, gnocchi with truffle oil, and sautéed zucchini with mint and hazelnuts.

The drinks were equally mysterious. I received my first glass during the fish course, which I correctly guessed was white wine. Given that, I decided the next glass must be a red. It was rosé. The dessert wine tasted like sparkling apple cider. It was white wine again, but with "arômes typiques de pommes."

Before we can get to dessert, however, we need to pass through the cheese plate. I nailed this one. It tastes like cheese. Slices are served with a tangy sauce that, in my view, could be anything from mustard to jelly. It's actually cherry jam and raspberry dressing.

The final course is a parfait in a latched glass jar. This one is easy. Rich chocolate, slathered over a fruit of some kind, topped with sprinklings of crumble. I thought the fruit was prunes since they are in season and we've been eating a ton of them while in France, but it's apricot. There's also supposedly Nepalese pepper and white cheese in the glass, but those flavors are mere hints at best, and easily overpowered by the chocolate and fruit.

Dinner over, our server once again organizes us into the human choo-choo train. It's been fun, but stepping back into the light, I'm overcome with the familiar sense of relief that often marks the end of a blind date.

It's difficult to say if Dans Le Noir changed the way I approach food. Any sensory differences noticed at subsequent meals were surely marginal. Toast may have been crunchier. Meats might have been juicer. A few days later, we stopped in a cat cafe for a drink only to be overcome by the scent of working litter boxes, but that observation might not be unique to dark diners.

The truth is, sight plays an important role in the sensory experience. Over-the-top decorative cakes and thoughtfully plated entrées aim to please our eyes as much as our stomachs. Clearly, we like to play with our food. Any extra attention I now paid to smell and texture was matched in the morning by visceral satisfaction accompanying the sight of fresh coats of melted butter diffusing into breakfast rolls and sips of hot coffee from dainty porcelain cups. I guess the trick to great sensory experience is similar to cooking itself—in that no one note dominates.