Classic Cookbooks: Cooking Price-Wise By Vincent Price

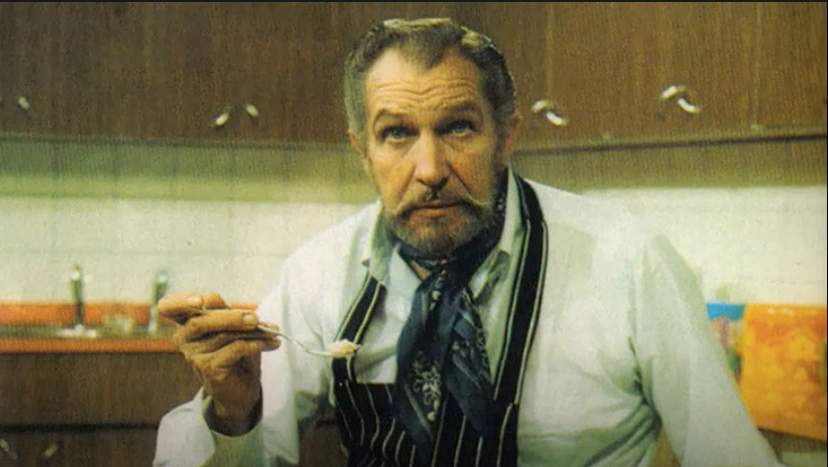

Vincent Price was many things: an art historian and curator, a philanthropist, a gourmet, and a celebrated stage, screen, and television actor. Of the 121 films he appeared in during his half-century-long career, only about 40 of them were horror movies.

"The reason, I suppose, that I've got stuck with the label of 'horror king' is that I'm so good at playing that kind of role," Price explained. But that's not quite it.

Vincent Price was not only good at playing that kind of role, he was good at parodying himself playing that kind of role on some of the campiest TV shows ever made—The Brady Bunch and Batman and Scooby-Doo—not to mention The Muppet Show, where he sat down with Kermit for a particularly incisive interview about the actor's craft.

You have to love someone who doesn't take himself too seriously—or maybe someone who takes himself just seriously enough. Who else would go on The Tonight Show to promote one of those horror movies, show off a Jackson Pollock painting from his personal collection, and then demonstrate how to cook a salmon in a dishwasher? Who else could?

Price's interest in cooking is generally attributed to his second wife, Mary, with whom he wrote three cookbooks, starting with A Treasury Of Great Recipes, originally published in 1965. But food was also part of his family heritage: his grandfather, Vincent Clarence Price, was the inventor of Dr. Price's Phosphate Baking Powder (and also published his own cookbook) and his father, Vincent Leonard Price Sr., was the president of the National Candy Company in St. Louis and served as head of the National Candymakers Association; when the younger, spookier Price was born, the National Candymakers honored him with a medal and the title "Candy Kid." Later on, sometime in the '40s, after he was already a movie star, Price returned to St. Louis to compete in the Globe-Democrat Cooking and Home Making School and, before a crowd of 12,000 people, donned a cap and frilly apron and prepared Bran Fudge Squares. "It's fun, really," he said at the conclusion of the demonstration. "I had little idea that cooking could be so simple or so enjoyable." By the time he became a cookbook writer, though, Price had developed some serious cooking chops: in the 1972 movie Theatre Of Blood, you can see him crack an egg one-handed and then beat it with a whisk in a copper bowl tucked under his arm.

A Treasury Of Great Recipes was reissued, with some fanfare, a few years ago, and it contains menus and recipes from some of the Prices' favorite restaurants they visited on their travels in the 1960s, ranging from Tour d'Argent in Paris to Sizzler. (They were enthusiastic fans of both.) I will not be writing about A Treasury Of Great Recipes because Gwen Ihnat has done it for you already.

Instead, I give you... Cooking Price-Wise: A Culinary Legacy (2017), based on Cooking Price-Wise With Vincent Price, a short-lived series Price hosted on Britain's ITV in 1971. (No one has posted any episodes online yet, but here is a summary of the first episode, "Potatoes.") It is, I would argue, a perfect representation of Vincent Price: a purportedly serious endeavor, requiring a certain amount of expertise, presented nearly straight-faced, just enough that you could take it seriously if you wanted to. But why would you?

The goal of the show, Price wrote in the introduction to the cookbook, was to introduce the British to food from other countries. "They'll eat spaghetti, for instance, if it comes out of a tin, chopped up short and smothered in tomato sauce, but the real thing, no matter how available it is, is quite beyond them," he wrote of the Brits, with whom he'd spent a lot of time since his days as a graduate student in art history at the University of London. (He had to give that up when acting began to take up too much of his time.) The producers of Cooking Price-Wise generously agreed to his plan to broaden Britain's culinary horizons, on one condition: all the ingredients needed to be available in regular British grocery stores. Research was done, soy sauce was located even on the island of Oban in Scotland, and Price's audience was introduced to such wonders as Fish Fillets Noord Zee, Matambre Arrollado, and Nasi Goreng. (And also fun historical facts about their own homeland: "In the thirteenth century cheese was used as a substitute for cement in England, when the cheese got stale, that is.")

"I must warn you, though," Price wrote in his introduction to the Cooking Price-Wise cookbook, "that some of the recipes come from a rather far-away place called Britain! Now the people of this country have very strange eating habits.... However, I can assure the more squeamish among you that I have only chosen the cleanest recipes from this unfortunate land. So with your cooker, instead of a jet-plane, come with me on a gastronomic tour of the world..."

And away we go!

Reader, prepare to be horrified. Everything you loathe and fear in mid-century cookery is in this book: Gelatin molds! Canned fruit! Lots of things stuffed into other things! Cream of mushroom soup! As Price himself might have said in that mid-Atlantic accent of his, "Ghastly! Ghastly!"

Price refused, perhaps wisely, to take credit for any of these recipes. He was a collector, he emphasized. But where he found Apple and Orange Stuffed Bacon I would desperately like to know.

I desperately wanted to make this dish (the apples and oranges are not metaphorical), but, alas, it required something called "a middle-cut bacon joint," not available in my American supermarket. So I settled for making Bacon Moussé, which only called for chopped bacon mixed with horseradish sauce, mayo, dry mustard, cream, and gelatin. I didn't have a mold, but it was easy to purchase an appropriate one online, with the support and encouragement of my Takeout colleagues and inspiration provided by Price himself:

(Okay, okay, this is an edited version of a recipe from The Vincent Price International Cooking Course, a series of educational records the actor recorded in the late '70s. It's adapted from the lesson on Indian curry. Which did not encourage the harming of small children.)

With about 15 minutes of mixing and a few hours of chilling, I ended up with this:

A poor defenseless bacon mousse baby needs someone to watch over it. Fortunately, Cooking Price-Wise had a recipe for that, too. Technically, it had two, but the one that initially caught my fancy, Melon Monsters (it seemed so Price-esque!), was tantalizingly incomplete. The list of ingredients did not include melons, nor were melons mentioned in the text of the recipe. Instead I resorted to the Crocodile Cucumber. Bewilderingly, it was included in the "Party Dishes Using Traditional Cheeses" section although the recipe didn't mention what to do with the cheese. The photo section in the back of the book, though, showed a croc spiked with cheese cubes.

I couldn't bear to do that to my own croc, which I named Vinny, in honor of, well you know.

Is that not a tender tableau?

Poor Vinny met a tragic end in the kitchen trash can—which I now imagine looms like a smoking sacrificial volcano for anthropomorphized food—a few days later when the pepper legs began to wither and white spots appeared on the cucumbery torso.

I have not been able to bring myself to eat the baby, even after it was, quite unfortunately, decapitated during the transfer back to the refrigerator. I had lots of extra mousse, though, which I'd poured into a bowl to gel. I finally tasted it. It was edible, but it reminded me how much I hate horseradish—perhaps something I should have considered before I went all-in on a recipe that features four tablespoons of it.

Cooking Price-Wise concludes with an epilogue by Price's daughter, Victoria, that includes excerpts from The New Dr. Price Cook Book, credited to her great-grandfather the baking powder magnate; bits of Price's travel diary from a high-school trip to Europe (he dutifully recorded the contents of various museums and churches he was taken to but seemed most genuinely impressed by a Parisian nightclub where white people and Black people danced together); and finally her own culinary memories of her father. Their kitchen time together was mostly on Saturday mornings when he was home from filming, and if there were gelatin and canned mandarin oranges around, she doesn't mention them. Instead they ate plain good food.

"I knew my dad loved to cook and to eat—and I loved learning how to make the things he loved," she writes. "Popovers and pancakes and scrambled eggs with bacon. But even more than that, I loved learning all his clever tips and tricks, because I felt like he was passing on things that only he knew. Little secrets that he was letting me in on. That made me feel special in a way that I don't think I will ever find the words to describe."

The recipes for popovers and buckwheat pancakes are presented with a great deal more thought and care than most of the recipes in Cooking Price-Wise, except for the ones that made the cut for the TV show. This confirms my theory that Cooking Price-Wise is, in many ways, a reflection of its author: part serious, part spoof, but always gracious and presented with a wink, because if Vincent Price was who he pretended to be, he would never have done all the things "Vincent Price" did.

And, at heart, there's basic warmth and kindness.

"Here are some of his secrets," Victoria Price wrote in the pancake recipe. "Mix oil and butter on a skillet at high heat. The combination of the two should prevent burning. The first pancake is usually not a keeper, so make it small and give it to your dogs."

In Price's honor, during the preparation of the Bacon Moussé, I made an extra strip of bacon for my own dog, Joe. (Price also had a dog named Joe, about whom he wrote a book: The Book Of Joe: About A Dog And His Man.) He appreciated it and looked up at me with doggy grin when I said, "Now that was a sumptuous meal, wasn't it?"