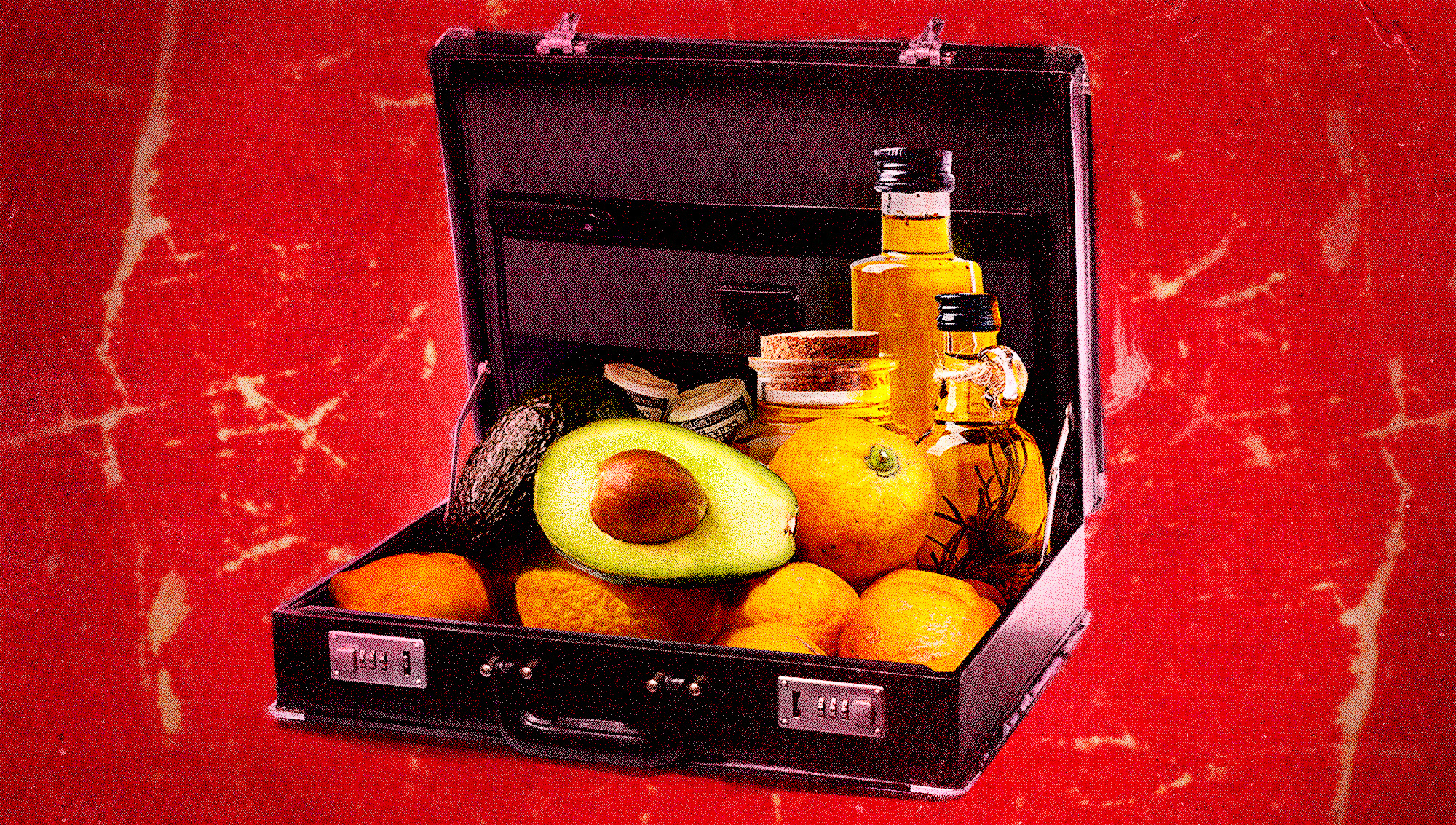

'Blood Foods' And The Violent Ties Of Your Favorite Ingredients

A look at the disturbing connection between organized crime and the most common pantry staples.

In the late 19th century, it was apparently common to find lemons nailed into the gates of citrus groves, and next to them shotgun cartridges dangling from strings, throughout rural Sicily—a clear signal that mafia clans laid claim to the orchards.

Citrus was increasingly big business on the island at the time, but citrus farms were still mostly small and fragmented operations, and the rule of law was weak. The mafia, then a nascent organized criminal outfit, decided to exploit that wealth and weakness by taking a cut of farmers' profits (for "protection"), destroying lemons to manipulate prices, and brutalizing anyone who tried to get in their way.

Lemon money helped fuel the rise of the mafia. And this wasn't some odd, one-off racket.

Mafiosi who moved to the US in the early 20th century used similar strong-arm tactics to create rackets around all kinds of produce, meat, and dairy. Famously, New York's tough-on-crime mayor Fiorello LaGuardia briefly banned baby artichokes as part of his effort to cut into mafia profits. And Al Capone got his hands so deep into the dairy business that he may have set standards for American pizza cheese.

Mike Dash, a historian of the early American mafia, has argued that violent food rackets were "one of the mafia's most important sources of income."

Until prohibition, that is, when the mafia pivoted toward the even more massive profits to be made on illicit booze. From there, they pivoted again toward other high-risk, high-reward ventures like drug and gun trafficking, gradually morphing into our modern image of organized crime: Tony Montana deals in mountains of cocaine, not cornstarch.

The murky world of modern food crimes

But even though we no longer associate the mafia with produce, criminal outfits never fully got out of food crimes. In fact, over the last couple of decades, as governments have cracked down on drug and gun trafficking, organized criminal groups in a few countries have increasingly turned their eyes toward trendy foods. Intimidating farmers, abusing farm subsidy programs, and adulterating or counterfeiting high-end foods is, after all, less risky than drug running but can be just as profitable, or even more so.

It's shockingly hard to tell what foods have been touched by violent crime, though. Following the 2013 "horsemeat scandal," governments around the world have poured more money into tracking and responding to food crimes, and they've developed a good sense of the massive scale of adulteration, counterfeiting, and other dangerous profiteering tactics.

"Anything that's unique, and has limited supply and high value is at risk" of adulteration, counterfeiting, or other criminal shenanigans, explains John Keogh, an expert on food supply chains and fraud perpetrated within them.

"Products with long, complex supply chains tend to be more vulnerable," added food fraud researcher Karen Everstine.

But most food crimes are the work of unscrupulous big businesses chasing profits or small producers facing economic hardship rather than violent, organized criminal groups. And official reports on food fraud rarely specify if, when, or how mob-type groups might have been involved.

However, we do know with relative certainty that at least a few common food items are (selectively) tainted by violent, organized crime. Writers have even compared some foods to conflict minerals, raw materials that insurgent groups use to fund their violent operations and perpetuate violence. Which of course makes the idea of casually consuming any of these comestibles ... complicated.

Your guacamole might be fueling drug cartels

Over the last 20 or so years, Americans have developed a borderline fanatical love for all things avocado. The rapid rise in demand brought prosperity to the Mexican state of Michoacán, long known as the center of the nation's avocado industry. But it also attracted the attention of the country's infamous drug cartels, especially those eager to diversify their sources of income in the face of heavy competition and crackdowns on drug trafficking.

A recent report by Mexican authorities actually alleges that a few of Mexico's most brutal young cartels fueled their early expansion primarily by exploiting the vulnerabilities of avocado producers.

As the security analyst Christian Wagner told The Guardian back in 2019, "From cultivation through transportation, violence and corruption now pervade Mexico's avocado supply chain... Association with killings, modern slavery, child labor, and environmental degradation is becoming an increasing risk when dealing with Michoacán suppliers and growers."

Over the last decade, avocado-producing towns have repeatedly tried to fight back against the cartels by creating mutual cooperation pacts between growers, processors, and shippers—and developing their own paramilitary forces. But despite these efforts, cartel incursions into and conflicts over avocado-growing land still seemingly flare up and cools down every few years.

Cheap meat is a dangerous game

Among many other cattle-related cons, criminal groups the world over roll into remote communities and strongarm their (often indigenous) inhabitants into giving up their lands so that either the criminals themselves or their clients can graze their herds without paying fees to governments or legitimate landowners.

In recent years, human rights groups have documented this violent grift in the Brazilian Amazon especially. A 2019 report notably claimed that land grabs for illegal logging and cattle ranching had led to at least 300 murders over the prior decade—and that's probably a lowball estimate.

Although these activities are illegal, oversight in the Amazon is notoriously difficult. And criminal groups have devised a number of tactics for laundering their illicit cattle into mainstream supply chains, and then onto our dinner plates. Cattle industry experts have stressed that they're working on improving supply chain traceability, in order to weed out such violent fraud. But that's slow going.

Olive oil is essential for cooking and crime

Fraudsters have been cutting high-end olive oil with cheaper varieties, or passing off other oils as "olive oil" by dying and mislabeling them, since the dawn of recorded history. The persistence of this con over the centuries makes sense: There's a huge price gap between something like extra-virgin olive oil and low-end olive pomace oil, but most consumers don't know the difference well enough to spot a fake. (Even those who do usually can't identify a fraud by just looking at a closed bottle in a grocery store.) So it's no wonder that food criminals have dipped into this amphora over the years.

In 2017, Italian cops busted a ring of olive farmers and oil producers with connections to the 'Ndrangheta, the Calabria region's answer to the Sicilian mafia, for selling fake extra virgin olive oil to global consumers. Reports at the time noted that the profits on their fake olive oil rivaled those associated with cocaine production, trafficking, and dealing.

Olive oil experts stress that the vast majority of EVOO in America is likely either adulterated with cheaper products, or just outright fake. It's hard to tell exactly how much of this oil fraud is associated with violent crime. But the 'Ndrangheta ring is likely not an exception.

Pretty much all Italian foods are cause for concern

Beyond specialty olive oils, Italian academics and officials report that organized criminal groups have worked their way into the nation's entire food system in recent years.

This incursion seems to be the result of state crackdowns on traditional mob rackets like arms and drug trafficking, which pushed gangsters to diversify. Around the same time, foodies worldwide signaled an increasing willingness to pay a premium for products from prestigious regions—like Italy. And an economic crisis left Italy's farmer's, food processors, and restaurateurs cash-strapped and vulnerable. So naturally, organized criminal groups decided to get involved in the market for well-known Italian goods like mozzarella de bufala and Parmigiano-Reggiano.

They've also been implicated in more complicated schemes, like sitting on unused farmland to wring subsidies out of states. And some endeavors are outright violent, like forcing small farmers to pay them protection money.

Most authorities estimate that Italian criminal groups make tens of billions every year—a notable amount of their total income—on food fraud and racketeering. Food crime is so important to these organizations now that a mafia group actually attempted to carry out what was arguably the nation's most ambitious mob hit of the last 30 years in order to stop a government official from cutting off their access to agricultural subsidies.

Increased scrutiny may start to put the screws on organized criminal involvement in the Italian food sector. The emergence of organized collectives of farmers, processors, and retailers who refuse to work with the mob, and do not bow to their threats and violence, may also break some of their stranglehold.

But for now, this nation's agricultural sector and food industry—and likely many others that we just don't know as much about—is clearly riven with criminal violence.

So, should we boycott these foods?

The obvious impulse, when one hears about a food item's connection to crime and violence, is to call for a boycott against the use or sale of that good to put the squeeze on bad actors. But many security analysts believe that's a bad idea, because it won't put a major dent in major criminal groups' budgets; they can always just pivot to new, more profitable, and less scrutinized fields.

However, boycotting these goods will almost certainly hurt the communities who rely on income from the sale of those goods. In fact, because modern supply chains are so complex and messy, even boycotts against one company or market are likely to affect producers who have no connection to organized crime at all.

What you can do to combat violence in the supply chain

Instead of pushing these "blood foods" off of our plates, we ought to use our power as consumers to demand greater transparency and traceability in supply chains. The more light we shine on the systems by which our food makes it to us, the less room there is for criminal groups to act.

Industry experts have tons of ideas for supply chain security and oversight improvements. But unless consumers and governments demand that companies throughout supply chains implement these new measures, few will go through the trouble of implementing them of their own volition.

So, go ahead and buy whatever avocados, beef, olive oil, and cheese you like. Just remember to make a ruckus about supply chain transparency and justice to anyone who might listen when you do.