The Strangest Old-School Restaurants We Can't Believe Existed

It wasn't that long ago, before the omnipresence of fast food, that eating a meal outside the home was a rare and novel thing. People didn't dine out as much as they do now, so when they did, going to a restaurant was an event. But the dining sphere has always been a competitive one, and restaurant operators knew they had to make their establishment stand out against all the others. Some of those who succeeded focused on the food — serving high quality meals, or just things one couldn't find most anywhere else. Others collectively invented the theme restaurants.

Almost like dinner and a show, theme restaurants turned eating out into entertainment, with such eateries discovering and executing ways to keep their diners entertained from the moment they arrive until they pay the check. That may include some performers, weird stuff hanging on the walls, or some combination of the two.

Over time, the notion of theme restaurants became absorbed into the mainstream; for example, the still operational Planet Hollywood, the surviving Hooters, and the Hard Rock Café. Others couldn't sustain life or turn their novelty into long-lasting success. Here are some all but forgotten restaurants of the past built on some of the wildest, weirdest, and most ill-advised ideas ever conceived.

Bugaboo Creek Steakhouse

Perhaps the most culturally entrenched theme restaurant format is the animatronics-enabled eatery. In the 1980s, the unsinkable Chuck E. Cheese's Pizza Time Theatre and ShowBiz Pizza Place attracted scores of kids and families with their frequent shows by robotic characters singing songs and playing instruments. The founders of Bugaboo Creek Steak House didn't understand why the only restaurants equipped with character robots were kid-centric pizza parlors, and so they opened up a small chain of steakhouses that served a more mature selection of foods.

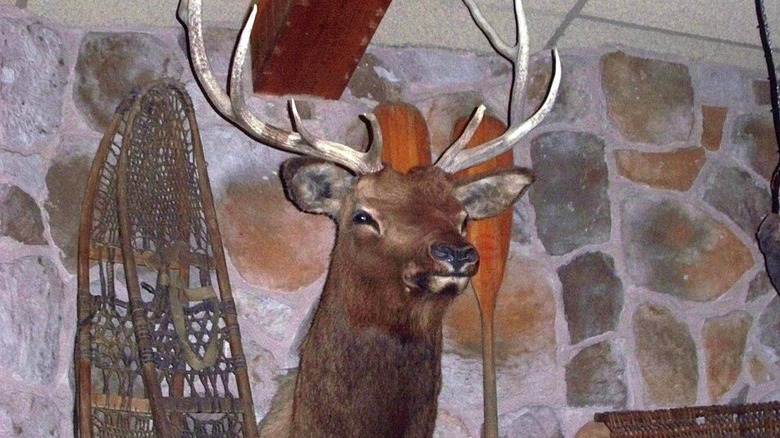

In 1993, the prototypical Bugaboo Creek opened in Warwick, Rhode Island. It was meant to look like a Canadian hunting lodge or a remote cabin, and its fake-log walls were adorned in what looked like the taxidermy-treated heads of deceased animals. Except those critters weren't dead at all; they were characters like Bill the Buffalo and Moxie the Moose who every so often would start moving and talking, spouting trivia about Canada's wilderness.

In 2016, parent company CB Holding Corp. shut down half of the 20 remaining Bugaboo Creek restaurants. By the end of the year, the chain was dissolved.

Organ Grinder Pizza

Organ grinders were late 19th-century street performers who played hand-cranked music boxes and were assisted in their busking by a small monkey. Organ Grinder Pizza didn't really do any of that stuff, but it was still weird that it helped set off a trend of restaurants in the 1970s and 1980s built around the idea that people wanted to hear gigantic pipe organs noisily bellow out old tunes from the 1800s while pizza was served.

The original Organ Grinder opened in Portland, Oregon, in 1973, and it displayed organs salvaged from old theaters and music halls. The establishment kept on its staff multiple organ players who kept the music flowing at nearly all times while families ate pizzas with musical names, like the taco-oriented Percussion.

Organ Grinder gave rise to other "pizza and pipes" restaurants, like another restaurant of the same name in Denver; Organ Piper Pizza in Greenfield, Wisconsin; Beggar's Pizza in Lansing, Illinois; and Organ Stop Pizza in Mesa, Arizona. The latter acquired organ pieces when the original Organ Grinder shut down in 1996.

Two Panda Deli

In the early 1980s, restaurant industry analysts were positive that before long, robots would take over much of the labor of serving humans food. Certified by Guinness World Records as the first spot in the United States to employ robots in that capacity, and to serve as a test run for what the future certainly would behold, was the Two Panda Deli, a Chinese-American fast food restaurant in Pasadena, California. In 1983, Owner Shayne Hayashi paid a total of $40,000 to import two bots, Tanbo R-1 and Tanbo R-2, and he put them to work as his food runners.

Both 4 ½ foot tall robots would travel from the kitchen to tables, delivering customers their food while also telling pre-loaded jokes. Programmed to ask "Will there be anything else?" and say "See you tomorrow" (via Smithsonian) in English, Spanish, and Japanese, neither Tanbo R-1 or R-2 was equipped to respond to customer questions, so they'd quip "That's not my problem" and then dance to disco music that played from an on-board speaker.

Two Panda Deli got a lot of media attention as a robot-themed Chinese restaurant, even though the main attraction often didn't function correctly. The robots frequently dropped trays of food, and interference from other radio signals, like police radios, made them stop working entirely. They'd also slur their words when their batteries ran low on charge.

Mickey Rooney's Weenie World

With his career as a top-earning child and teen actor long behind him by the mid-1970s, movie star Mickey Rooney attempted a series of businesses, perpetually trying to re-amass the fortune he once had. After failing to secure financing for a chain of Wiffle Ball-based, 24-hour, indoor golf courses, Rooney tried to get the money himself, unsuccessfully marketing women's cologne, bald spot paint, a laxative, and diet aids. Finally, one of his businesses took off: Mickey Rooney's Weenie World, part of the spotty history of celebrity-owned restaurants.

A hot dog-based fast food chain, the menu and business were built around an item that Rooney claims to have invented himself: the Weenie Whirl, a frankfurter that came in a round, ring shape, and which could fit neatly inside of a hamburger bun. Toppings were stuck inside of the O, and made for different menu items. While a standard issue Weenie Whirl came with mustard, A "Yankee Doodle" was a Weenie Whirl with cheese, sauerkraut made it an "Eric von Weenie," a chili dog was a "Pancho Weenie," and the combination that nobody asked for — raisins and pineapple — made for a "Surfboard Weenie."

Rooney managed to get franchisees to open two Weenie World outlets in 1980, one in New Jersey and one in Long Island. Neither restaurant was open for long.

Pat Boone's Dine-O-Mat

When rock n' roll emerged in the 1950s, white singer Pat Boone made a fortune recording sanitized, toned-down versions of more raucous songs previously released by Black artists. He covered Fats Domino's "Ain't That a Shame" and Little Richard's "Tutti Frutti," and made some ballads and country tunes, too, but when Boone's career started to falter in the early 1960s, he tried to parlay his earnings into other, more long-term and sustainable sources of income. One big idea: a restaurant chain called Pat Boone's Dine-O-Mat.

Housed in a window-covered, futuristic-looking geodesic dome, Pat Boone's Dine-O-Mat adopted a "space age" look with a "revolutionary" approach to food preparation, according to marketing materials (via Restaurant-ing Through History). Inspired by Horn & Hardart's automats, the early 20th century chain of self-serve cafeterias where customers obtained individual food items from small boxes unlocked with the insertion of coins, each Dine-O-Mat required just one employee. They stocked coin-operated machines with a variety of fully cooked and then fully frozen food items, which customers would then heat up in one of a few provided microwave ovens, at the time a brand-new and unfamiliar technology.

The first Dine-O-Mat opened in 1962 in Little Ferry, New Jersey, serving travelers off of Route 46. Other outlets may have briefly been operational, but the whole business fell apart in 1964 over financial problems.

Monk's Inn

Cornering the market on the niche of restaurant patrons who enjoyed ancient religious rituals as much as they liked cheese, Monk's Inn opened in New York City in 1969. An inexpensive restaurant situated in the otherwise ritzy area outside Lincoln Center in Manhattan, it was a hip place for performers at the venue to gather after shows and eat cheese and cheese-based entrees. That's pretty much all that was on the menu, apart from wine, and the cheeses used to prepare the offerings on the Monk's Inn menu were all put on display for customers to inspect on a large table in the middle of the establishment's modern dining room.

Cheese would be enough of a theme, but that just secondary to the main idea of Monk's Inn. The restaurant was staffed by male servers, who wore brown robes with cords for belts, just like the cloistered monks of European monasteries from the Middle Ages.

C**n Chicken Inn

The theme of this 1920s theme restaurant was a casual but aggressive, oppressive, and mocking form of racism. The full name of the place, because its first word was a blatant and common racial slur used to degrade Black Americans, can't even be published today. The experience at C**n Chicken Inn began when patrons entered the front door, which was made up to look like the cartoonishly oversized mouth of a smiling caricature of a Black railroad porter, an image that recurred throughout minstrel shows and vaudeville as employed by "blackface" performers.

Inside, patrons of the C**n Chicken Inn – restaurants were established in suburban Salt Lake City, Portland, Seattle, and Spokane, Washington — were served fried chicken, a food stereotypically associated with Southern Black Americans. Between the 1920s and the 1950s, C**n Chicken Inn did such tremendous business that it operated its own industrial bakery and poultry farm to supply its four restaurants. By the end of the 1950s, owners Maxon and Addie Graham decided to get out of the restaurant business and lease out their buildings to other restaurants.

Laugh-In

With a name evoking the protest-adjacent "sit-ins" and "be-ins" of the time, the quintessentially late 1960s show "Rowan and Martin's Laugh-In" capitalized on the countercultural vibes of the era with its psychedelic set imagery, quick-cut cinematography, and go-go dancers. By the 1968-1969 TV season, "Laugh-In" was the No. 1 show on TV, indicating a market for a restaurant that looked, sounded, and felt like the comedy-variety program. Clifford and Stuart Perlman already built the now-extinct hot dog-focused Lum's into a national chain and had just launched Abner's Beef House, and the Laugh-In eatery was their follow-up in 1969. The Perlmans' financial advisers were against the idea, because if (or rather when) "Laugh-In" were to get canceled, they'd wind up with an unsustainable and instantly dated restaurant chain. Nevertheless, they pushed forward, interesting as many as 40 franchisees and opening at least one outlet.

The outside of a Laugh-In restaurant was adorned in psychedelic-patterned panels. On the inside, tables were topped with printed graffiti plates upon which the many catchphrases of "Laugh-In" had been written. The menu was mostly burgers and sandwiches, but named after "Laugh-In" characters and sketches, like the Bippyburger, Fickle Finger Franks, Fickle Fingers of Fate Fries, and Sock it to Me soup.

The original Laugh-In restaurant lasted less than a year in Hollywood, Florida, while most of the others closed down shortly after the increasingly irrelevant "Laugh-In" went off the air in 1973. A Chicago franchise stayed open until 1988.

The Pyramid Supper Club

Supper clubs were a dining and entertainment format which proved particularly popular when Midwesterners went fancy in the 1950s and 1960s. Customers, or members, would wile away entire evenings at these establishments so large they had to be placed on the wide-open outskirts of major cities, where they'd drink cocktails, enjoy a multi-course meal, and then watch a nightclub act like a comedian or singer perform. Supper clubs didn't often take on a theme beyond elevated or elegant, but the Pyramid Supper Club sure did.

Just outside of Milwaukee, on a flat, plain area with no other buildings very close by so as to imitate the vast desert of Egypt, stood a 40-foot-tall replica of a centuries-old pyramid. Opening for business in 1961, when the U.S. was in the midst of an ancient Egyptian fad and fascination spawned by the touring museum exhibit of King Tut's treasures, the pyramid housed a large dining room where decorative columns bore elaborate hieroglyphic-type art.

The servers dressed in Egyptian-inspired garb and ordered off of pyramid-shaped table-topping menus. While it touted an Egyptian dining experience, the proprietors just meant the atmosphere; the food served was distinctively sit-down American, like "Pharaoh's Prime Rib." Later operating under various names, such as the Nile Club and the Pyramid of the Nile, the Egyptian-styled supper club closed down in 2009. The imposing building was torn down in 2025.

Magic Restroom Café

Second only to the kitchen, where food is prepared and cooked, the bathroom is arguably the most food-adjacent room in the house, because that's where anything eaten and processed ends its biological journey. Apparently getting the idea from waste elimination via the comforts of indoor plumbing, as well as from Taiwan's similar Modern Toilet restaurant and tourist trap, the Magic Restroom Café debuted in City of Industry, California, in late 2013.

Most everything at the Magic Restroom Café related to toilets and the act of moving bowels. Diners sat on modified toilets bolted to the ground and topped with lids turned down, and the walls in the dining room were lined with various patterns of bathroom tile. The food was rooted in the culinary traditions of Taiwan, but the dishes were given generally non-descriptive and rather gross titles that called attention to how many of the dishes were soupy, brown-colored curries that resembled human waste, including "Black Poop" and "Smells Like Poop." No matter what was ordered, it arrived at the table inside of a miniature toilet. The Magic Restroom Café did its business for about eight months before it evacuated.

Piratz Tavern

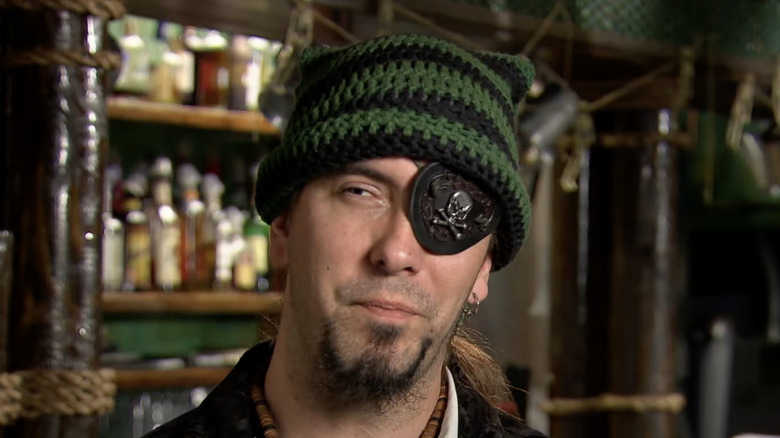

Tracy Rebelo combined her dream of owning and operating a restaurant with her love of Halloween parties, and in 2007 officially opened Piratz Tavern, a bar and restaurant with a deep and abiding dedication to pirate legends and lore. The Silver Spring, Maryland, business attracted a loyal audience with its ribald, high-energy atmosphere and wood-based design that made Piratz Tavern resemble a pirate ship or a secret pirate hideaway. In addition to a long and complicated menu of bar food, and a signature drink of grog, servers in pirate costumes maneuvered around a sword-swallowing bartender, fiery baton wielding performers, and shanty singers.

Piratz Tavern was popular but poorly run, to the point that the restaurant appeared in a 2012 episode of "Bar Rescue." Host Jon Taffer transformed the pirate bar into the upscale and generic Corporate Bar; the staff hated it so much that within a week it was Piratz Tavern once more. The decline continued, however, and a second "Bar Rescue" makeover couldn't save the place, and Piratz Tavern sailed away in 2015.

Mars 2112

At the New York restaurant Mars 2112, tourists could eat on the distant red planet, or at least the kitschy, low-budget, science-fiction movies from the 1960s idea of Mars. Occupying 33,000 feet in Times Square, Mars 2112 — named for the far-off, futuristic year of its setting — was the largest theme restaurant on the planet upon its opening in 1998.

Customers walked past a large frozen saucer into a futuristic waiting area where they were given their space travel passports and sent on a simulated rocket shuttle to Mars through a digital effects-laden wormhole. Then, diners were seated in the massive dining room (or head to the spacey bar for adults or the Cyber Street arcade for kids) to dine on "Primary Orbits," entrees like burgers, salmon, steak, the "Martian Soup of the Day," "Quasar Quesadillas," or the "Cosmos Cobb Salad."

The immersive, three-story Mars 2112 experience was successful enough to launch a second location in Schaumberg, Illinois, in 2000, but it closed in 2001. In 2012, the original Mars 2112 was grounded, too.