Classic Cookbooks: Beeton's Book Of Household Management, Edited By Isabella Beeton

If time travel ever becomes an option, I'd prefer my first expedition to be to Victorian England. It's not that I have any special affinity for the Victorians—I'm sure the corsets and hoop skirts (or bustles, depending on the decade) would be very uncomfortable, as would the London smog. But the Victorians did an excellent job of documenting their own lives in magazines, novels, and, most crucially for a time traveler's purposes, household management guides. If you studied these books closely enough, you could, in theory, show up in Victorian England and fit in reasonably well. Or at least, you'd know how to live within your means and understand the rules of polite social discourse, and most of all, you'd be able to eat. You might come off as a little odd, sure, but like the Coneheads on SNL a century later, you could also pass yourself off as "from France," and who would really know the difference?

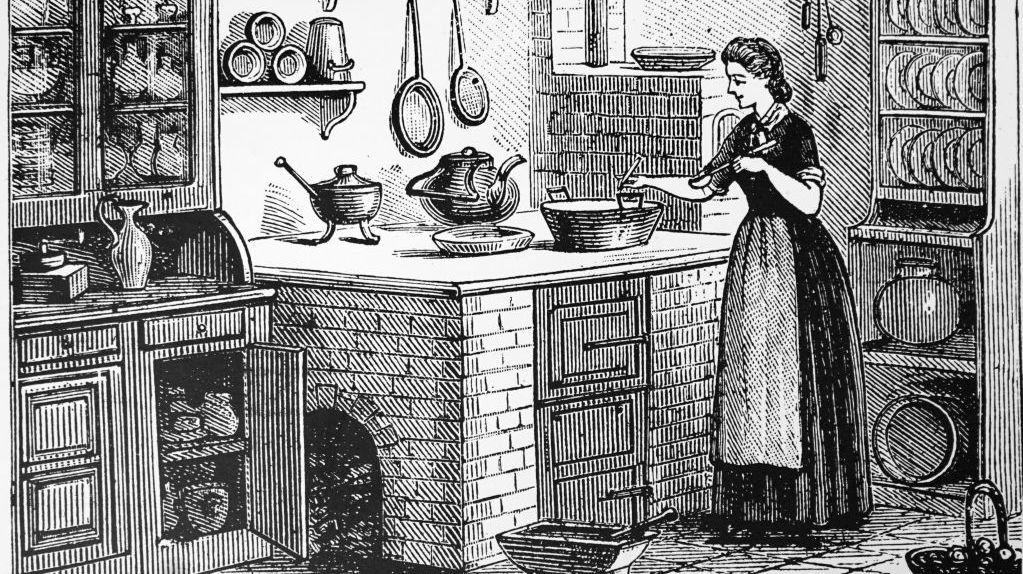

If you were to choose just one of those guides, though, best make it Beeton's Book Of Household Management. First published in installments in the Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine starting in 1859, it appeared in one massive 1,100-page volume in 1861, and it promised not only to provide instruction in every aspect in running a home, but also "a history of the origin, properties, and uses of all things connected with home life and comfort." This included descriptions of household duties for everyone (including a chart of how many servants one should have, based on household income), instructions on how to take care of children and cure minor illnesses and ailments; advice on, among many other things, how to maintain a friendship, host a dinner party, and buy a house or a horse; and, most of all, recipes, hundreds and hundreds of pages of them, from Apple Soup to Whiskey Cordial.

There were other housekeeping manuals. Of course there were! But over the years, Beeton's became the gold standard, not just for its wealth of information, but because, as the years went by, the publishers managed to give the impression that it had not been produced by an actual human being, but by an ageless domestic goddess: Mrs. Beeton. Mrs. Beeton was practical, organized, and a fount of information, sort of like a combination of Betty Crocker, Emily Post, Marie Kondo, and Queen Victoria. Over the years, she changed her clothes and hairstyle to fit the times, but if her name was on a book, it was a sign to the general public that they could trust it, much like the Good Housekeeping seal of approval. Eventually, after a century, "Mrs. Beeton" would become a committee of 55 experts, and not one of the recipes from the original 1861 edition would survive. Such is life. Dead women cannot write books. It remained in the best interest of the publishers to maintain the myth of the goddess and ignore the woman who inspired her.

Because, yes, there was once a real, live woman named Mrs. Isabella Beeton. And possibly the most surprising thing about her was that she was not the starchy old Victorian lady most readers imagine. (And why is it that we think of household management as the preserve of starchy old ladies anyway?) Isabella Beeton began writing BOHM in 1857 when she was a starchy old thing of 21. At the time, she had been running her own household for less than a year. Her husband, Sam Beeton, was a publisher of both books and periodicals, including the Englishwoman's Domestic Magazine, and he found that getting his wife to contribute regular articles about cooking and childcare eased his editorial budget immensely.

When Isabella married Sam, her entire cooking expertise comprised of some cooking instruction at boarding school in Germany and, upon her return to England, lessons with a local baker in how to make fancy cakes and pastries and fudge. She knew a bit more about raising children: she'd been the oldest of four. Her father died when she was still very young, and when her mother remarried, it was to a widower with four children of his own. The happy couple then proceeded to have 13 more children together. If you're keeping track, that's 21 total. (And yes, that was an enormous number even for Victorians. One of Isabella's stepbrothers, once he learned the mechanics of human reproduction, gave his father a condom as a gift. This would be a funny story, except that as punishment, he was shipped off to sea and drowned three years later in Sydney Harbor.) As the oldest girl, Isabella was her mother's chief assistant in childcare. Her stepfather, Henry Dorling, was a printer who became Clerk of the Course at the Epsom Downs Racecourse outside of London. Since there were only a few racing days every year, the Dorlings used the Grandstand to house the overflow of children who couldn't fit into the family home in town, and Isabella was usually the one in charge.

It's entirely possible that all this time supervising a herd of small children helped Isabella develop the authoritative tone she would use to great effect in BOHM. (And is it any wonder she dashed off to marry Sam Beeton, despite her family's disapproval—they found him coarse and obnoxious, and he didn't care for them any better—when she was just 20 years old?)

So, you might be asking, how did Isabella, with so little household management experience of her own, come to write such a doorstop of cooking and cleaning advice? The answer is that she obtained all her knowledge the old-fashioned way: she stole it.

In her excellent book The Short Life And Long Times Of Mrs. Beeton, historian Kathryn Hughes provides an extensive accounting of all of Isabella's thefts. Mrs. Beeton was extremely well read and fluent in both German and French, and she plagiarized only from the best chefs and home cooks of the 18th and 19th centuries—which one would have to do in order to fill 1,100 pages not just with recipes but with dubious historical and scientific background material. To be fair, plagiarism laws were looser in 19th-century England than they are now, and many of the authors Isabella stole from most flagrantly were dead. And also, Isabella was described on the title page as the book's "editor," not its author.

Anyway, nobody remarked upon this when BOHM made its debut, and it received mostly positive reviews, even from prestigious publications that usually didn't care at all about housework (that is, magazines intended for men), such as the Saturday Review and the Athenaeum. They praised Mrs. Beeton for providing solid advice for middle-class housewives who didn't employ a plethora of servants and, most of all, for teaching them how to create a system of household management: "It is not money," the reviewer in the Athenaeum wrote, "but management that is the great requisite." As Hughes points out, the Victorian age was also the age of the Industrial Revolution, and the Victorians loved themselves a good system.

BOHM is not an entertaining read. The prose can be cluttered and wordy, especially in the history and science chapters, which read like the work of a student who frantically crammed everything she could from the 1860s equivalent of Wikipedia. But when it comes to cooking, Mrs. Beeton is all business. After a brief introduction and the table of contents comes a 30-page index where readers can find what they're looking for in a hurry. The book is organized by paragraph, not pages, in order to make things even easier to find. (The indexer must have been a marvel.) The recipes contain not just a list of ingredients and instructions—seldom more than a paragraph—but also the time it takes to make it, how much it costs, which season it should be served, and how many people it feeds. Home economics, along with precise kitchen measurements, would not be invented for another three decades, but Mrs. Beeton, with her keen interest in how much a penny could be stretched, paved the way. And for a cookbook writer of her time, she was remarkably precise. Where another writer would say, "Take a small lump of butter," Mrs. Beeton offers measurements by the ounce, and in her introduction to the cookery section, she explains precisely what she means by "a table-spoonful," "a tea-spoonful," and "a drop."

I would not be inclined to try any of these recipes today, though I do enjoy that the recipe for Turtle Soup begins with the matter-of-fact instruction that "to make this soup with less difficulty, cut off the head of the turtle the preceding day." (If you can't afford a turtle, Mrs. Beeton counsels in a note, you can always buy canned turtle meat. She offers no consolation to anyone who might be squeamish about beheading a turtle.) For better or for worse, modern recipes, the ones I learned to cook with and the ones I edit here, have a lot more coddling: explanations of what foods should look and smell like at different stages of preparation, what to do if things go wrong. But for its time, the BOHM was remarkably helpful. At the very least, it didn't assume that its users already knew how to cook everything. Its tone was matter-of-fact, even bossy. You followed Mrs. Beeton because she knew best. Or, as the 20th century food writer Elizabeth David—herself no stranger to an authoritative tone—would put it, "Mrs. Beeton commands... Her pupils obey."

The BOHM was not an immediate success. Sam Beeton claimed that the initial printing sold 60,000 copies, a fair number, but hardly a blockbuster. Other publishers came up with their own versions. But cooks preferred Beeton's because of its authoritative tone and vast catalog of recipes. They began recommending it to one another and giving it as a gift to young brides. Gradually, sales began to increase. In 1888, a second, expanded edition was published; this one was 1,600 pages. In 1906, a brand-new 2,000-page full-color edition appeared, weighing six pounds. By then, "Mrs. Beeton" had been elevated to her position as Great Britain's chief domestic goddess.

Isabella Beeton never knew any of this. She died in 1865, just after giving birth to her fourth child. The cause was puerperal fever, an infection common among women whose babies were delivered by doctors who hadn't properly washed or disinfected their hands (something that wasn't discussed in BOHM, either). She was just 29. By then she had become an equal partner in the publishing firm—the Beetons took the train to work together—and after her death, it all fell to pieces. In 1866, Sam Beeton declared bankruptcy and sold all his magazines, copyrights, stock, and equipment to another publisher, Ward, Lock, and Tyler, for whom he went to work as an editor. It was Ward, Lock, and Tyler (later Ward, Lock) that prospered from the enshrinement of Mrs. Beeton.

Curiously, all future editions of the BOHM, now known as Mrs. Beeton's Book Of Household Management, never mentioned that Mrs. Beeton had ever been an actual person, or that she was now dead. As far as the public was concerned, that was all beside the point. What did it matter who had compiled all those recipes and all that information in the first place? The Book existed. Mrs. Beeton was immortal.