4 Lessons From A Post-Graduate Course In Omelettes

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

There are obvious breakfast foods; there are obvious lunch foods; and there are obvious dinner foods. It's a bit strange if you think about it for more than two seconds. Why is cereal consigned to hours before 10 a.m.? Why does it feel less appropriate to eat a sandwich outside the window of 11 a.m. and 2 p.m.? Why is bacon and sausage acceptable for breakfast, but ask for baby back ribs in the morning and people think you're a nutcase?

Recently I spent an evening date at a Chicago restaurant called Cafe Marie-Jeanne. On its dinner menu were four omelettes. My knee-jerk reaction was it was some cute breakfast-for-dinner gimmick, but I quickly remembered omelettes are served all hours of the day at French bistros. And if a restaurant was ballsy enough to offer a dinner omelette alongside duck frites with seared foie gras and black bass in beurre blanc sauce, then the kitchen is signaling to me their omelettes are not-to-be-missed. I took the plunge and ordered one with bacon and chanterelles.

My omelette consumption heretofore were of the Denver variety or some overwrought creation constructed at a hotel buffet. They all shared one commonality: Those omelettes could've been classified as a burrito—a cylinder of rubberized eggs stuffed to cliff's edge with meat-and-vegetable filling. The egg in those omelettes wasn't the star of the show; it was merely a container for sausage, cheese, and onions.

When the bacon-and-chanterelles omelette at Cafe Marie-Jeanne arrived, my first thought was an egg negligee, sheer and seductive. It was the opposite of the ostentatious mounds defining other omelettes. This was prim and proper, an understatement. What struck me was the total lack of give on my first bite. In the same manner cotton candy disappears, this omelette dissolved into just the notion of an omelette. Airy wasn't the word; airy implied nothingness, and something was definitely there, however ephemeral—bacon smoke, meaty mushroom, butter, richness.

My sample size was small, but I'll be damned if it wasn't the finest omelette I'd ever tasted. Maybe this was how they're supposed to be.

A week later I visited the kitchen of Cafe Marie-Jeanne between lunch and dinner service. I had reached out to its chef, Mike Simmons, who agreed to reveal his omelette secrets. The 60 minutes that followed comprised a post-graduate course in egg-handling, certainly the most intensely I've ever ruminated on this dish. My omelette proficiency had been forever divided into a before and after. Here, I share with you those lessons I learned on that fateful day.

1. Know what you’re working with

Chances are you don't have restaurant-grade equipment in your home kitchen. Not to worry: Simmons said an 8-inch Teflon-coated, non-stick pan worked just fine. Also, a heat-resistance spatula "is your best friend when you're making omelettes at home." (Because they cook on a flattop, Simmons uses a drywall tape knife when making their omelettes: "It's got a very thin blade, and an omelette fits and flips perfectly with it.")

As for ingredients: good-quality eggs, obviously. Butter: Simmons likes cultured butter, which adds a perceptible tang. Sherry—sherry!—because a few splashes go fabulously with eggs. Dill and chives are great. Crème fraîche if you're up for it.

2. However you make an omelette, it’s probably overcooked

Simmons makes any cook who prepares and serves an omelette at his restaurant first go through a test. He demonstrated: Simmons took a pat of butter and evenly paint-brushed an area of about 10-by-10-inches. The butter didn't even sizzle; the temperature of the griddle is kept between 200 and 225 degrees Fahrenheit ("low" on home stoves). Simmons ladled scrambled egg onto the buttered surface, and within seconds, began folding the barely cooked egg into a roll using that drywall taping knife. Within 30 seconds, it was off the heat. Simmons cut into a chunk from the middle and made me taste it. My teeth sank through with no resistance.

Still, this was overcooked for Simmons. "I wouldn't sell this. It's snappy and it's not custard. You don't sense any creaminess." It took two more tries until Simmons made what he'd considered a passable texture. That third try? Custardy. Creamy. It was the nanosecond after time zero when egg proteins began binding together.

3. Understand the structure of an omelet

Here's what I previously knew of omelettes: Beat eggs, pour into pan, pile on filling, fold into thirds, serve. There's no standard-operating omelette, but if I must make educated guesses, I will presume the American ideal of omelettes is more meat-and-cheese heavy than its French counterpart. I will presume a proper French omelette uses meats and vegetables as an accent mark.

The biggest eye-opener during my hour at Cafe Marie-Jeanne was learning how they engineered their omelettes: They took barely cooked scrambled eggs, added it atop that gossamer-thin layer of egg, then folded it onto itself. The crepe-like package would spend all of 25 seconds total on the griddle. Essentially, this omelette is scrambled eggs wrapped in a sheer, seductive sheet of egg.

Simmons demonstrated how his restaurant made scrambled eggs. In a heated sauce pan, he generously splashed in some sherry, allowed the alcohol to cook off, then added a big chunk of butter. He then poured in four scrambled eggs and immediately began stirring with a heat-resistant spatula. (At the restaurant, the cooks puts the eggs through a blender and strains it.) Simmons would take the sauce pan on and off the heat source, purely on feel. "You're making a curd," he said. When it began to look like wet porridge—about 40 percent cooked-through—Simmons transferred the scrambled eggs into a bowl to stop the cooking. He mixed in chives.

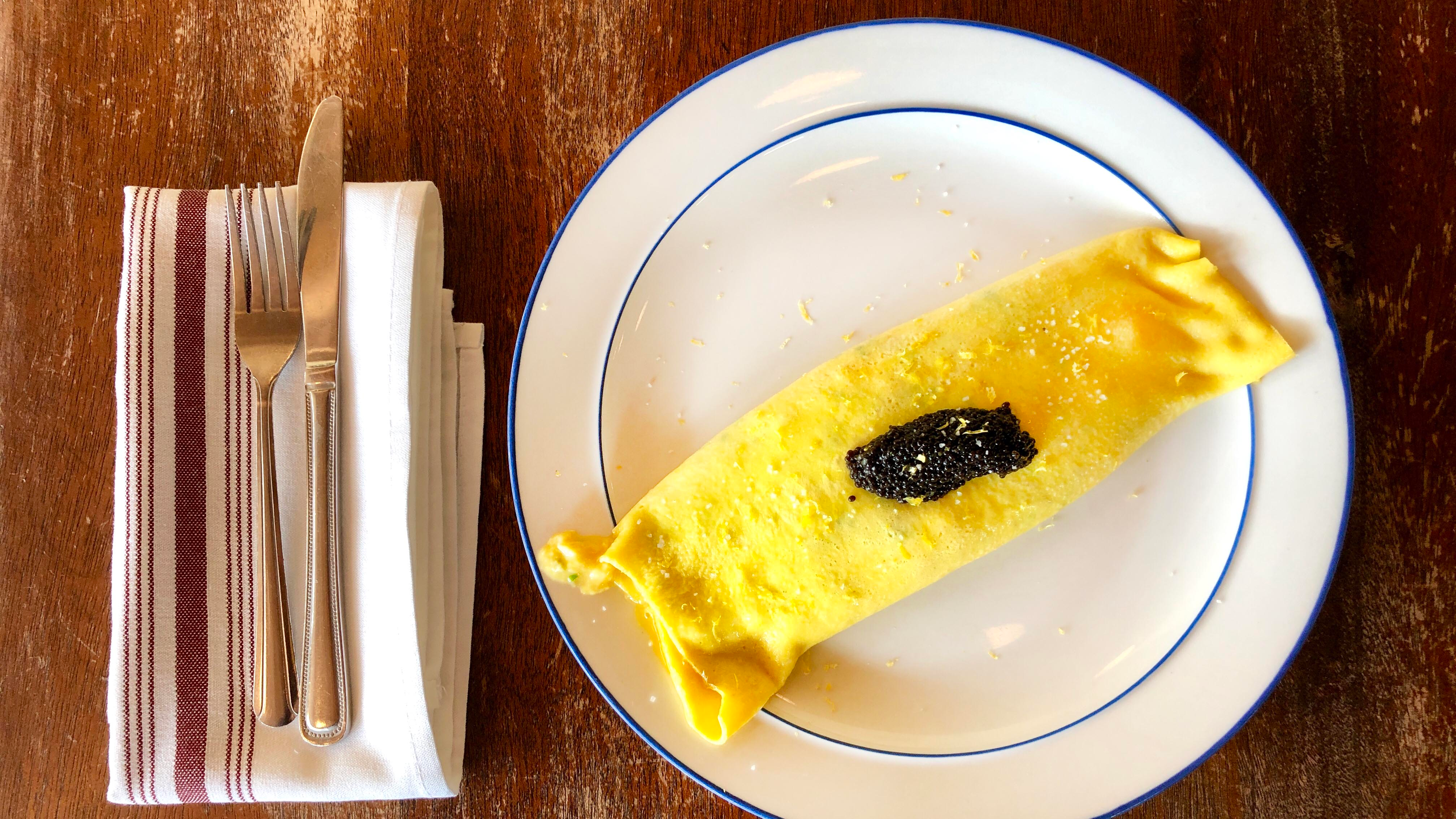

Time was of the essence. Simmons paint-brushed butter onto the griddle, ladled on eggs, and trimmed off the sides to form a square. Within 15 seconds, he spooned the 40-percent-cooked scrambled eggs with chives (by this time probably 50 percent because eggs continue cooking through residual heat) onto the square sheet of egg. Within 30 seconds, Simmons folded it into an omelette. By second 35, the omelette was on the plate and awaiting a spoonful of caviar.

4. Once you master the basics, go wild

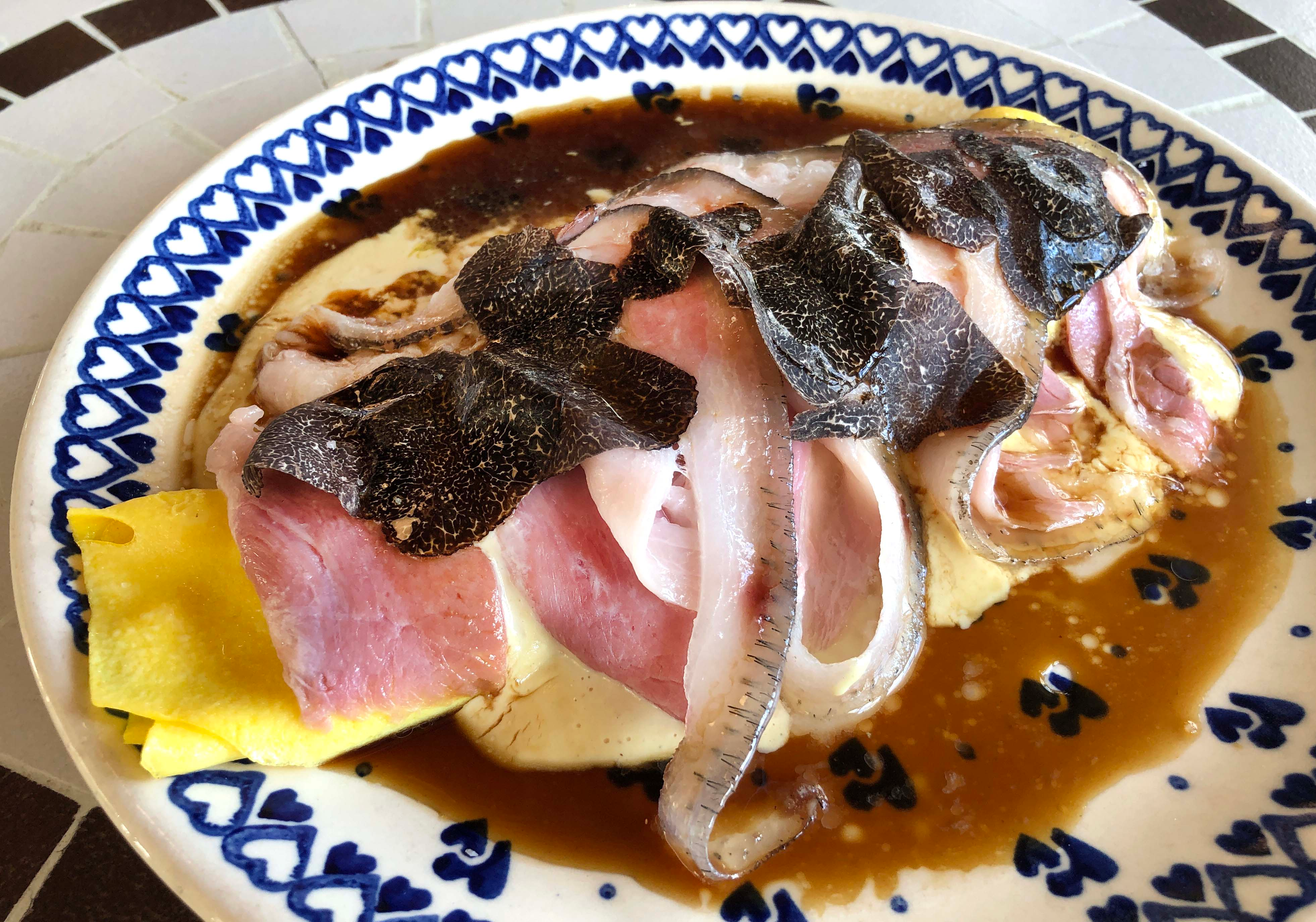

I included this "lesson" here not because it's particularly practical for home cooks, but as a way to expand our worldview of what's possible with omelettes. It began with Simmons telling me that he sought an over-the-top omelette for his menu. What he conceived was a thing of frightening Franco-American beauty. At its base was that custardy, creamy, eggs-wrapped-eggs omelette. Then came a sauce of Epoisses Berthaut—a barnyard-y, beautifully stinky cow's milk cheese. On top of that Simmons draped in slices of house-cured Mangalitsa ham. He placed this beneath the broiler to make the fat glossy. Finally he shaved a ransom's worth of Perigord truffles, and poured a warmed veal-pork jus tableside. At $32, it was positively Joe Beef-esque in its excess, and you could barely take more than four bites before throwing in the towel. But during those four bites you could swear God existed.

To review

- Begin with good eggs, good butter, a good non-stick pan, and a heat-proof spatula.

- Extra credit: Chives, crème fraîche, a splash of sherry.

- Keep the temperature very low, no more than 225 degrees Fahrenheit. You don't want your butter to sizzle, only to melt.

- Take your omelette off the heat quicker than you'd think. You're trying to achieve a custard-like texture.

- Consider constructing your omelette using barely cooked scrambled eggs, adding it onto an egg sheet, then folding it up.