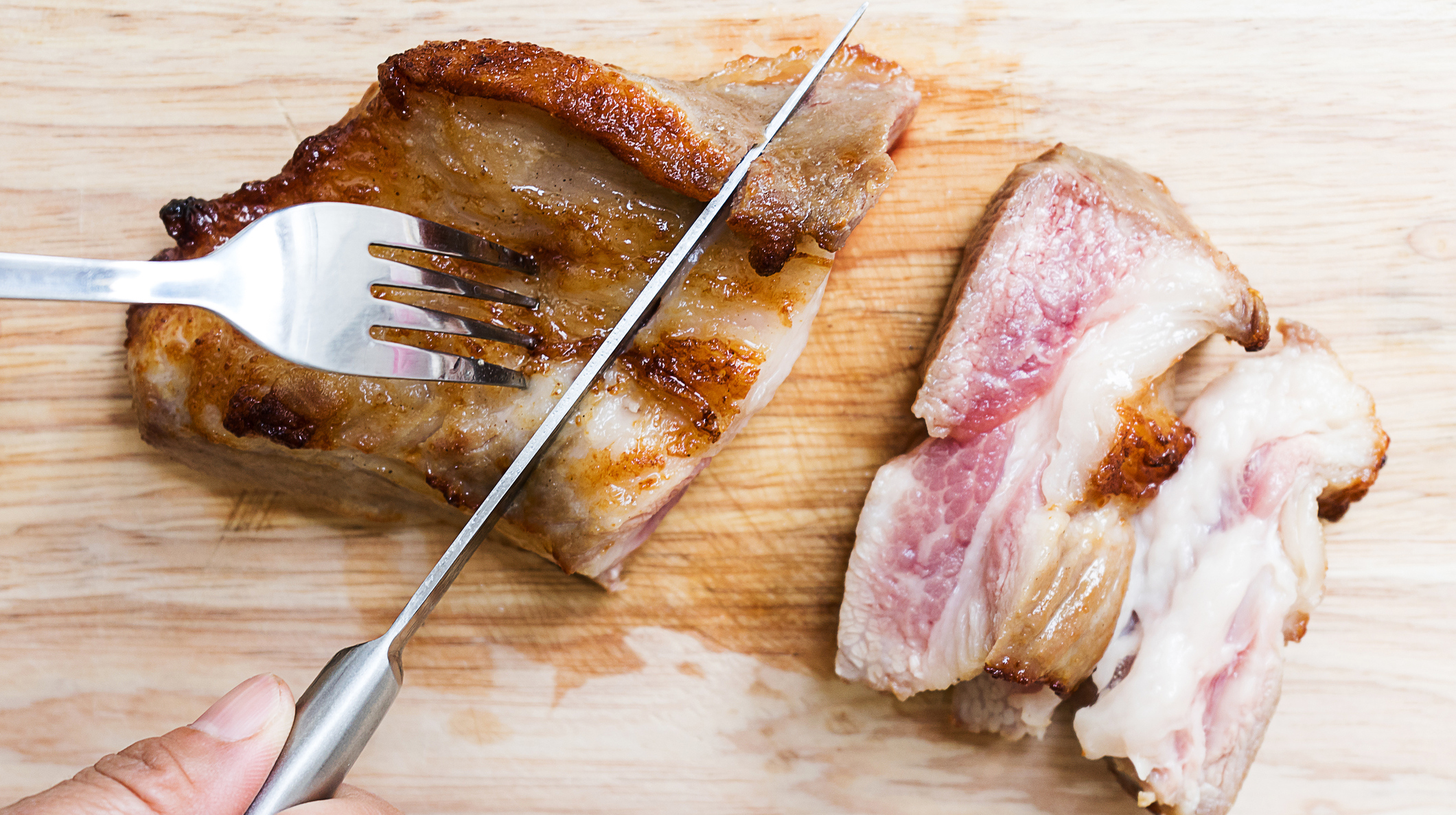

We Should Be Eating Medium-Rare Pork

The stigma against well-done steak does not extend to its white-meat cousin, pork. Americans don't think twice before cooking our pork chops until they're white (verging on gray) throughout, and some people might even squirm a bit when served a pink-center tenderloin. But friends, that's wrong. To avoid the menace of shoe-leather pork, we should in fact be cooking it to medium-rare.

"I think a lot of pork has tended to be overcooked, and that traces back to when trichinella was considered a huge issue in pork. Most people grew up on pork being traditionally overcooked, even myself," Martin Bucknavage, senior food safety extension associate at Penn State's Department Of Food Science, tells The Takeout. "When it comes to pork, a lot of people don't even use a thermometer, they just cook the hell out of it."

Arbiters at the National Pork Board are here to change those hearts and minds. The organization recommends cooking pork loins and chops to an internal temperature of 145 degrees Fahrenheit—that's a pink-centered medium rare, folks—followed by a 3-minute rest before serving. This wasn't always the case: Prior to 2011, the typical recommendation was 15 degrees higher. (Ground pork, however, should still be cooked to 160.) What changed?

"Meat generally continues to cook even after it's removed from a heat source so this just acknowledges that," Kevin Waetke, vice president of strategic communication for the National Pork Board, tells The Takeout. "If you cook it until it's gray or white on the heat, and then you remove it, then it's going to continue to cook until it's a dry and leathery. And no one wants that."

Research in the early part of this decade found that, following a 3-minute rest, pork cooked to 145 degrees is safe to eat. Since most Americans' food realistically does sit for at least three minutes before they eat it, this became the new industry standard.

But what about trichinosis and other nasty illnesses that can come from undercooked meat?

"Gone are the days of foodborne pathogens that did require a more thorough cooking. Back in the 1930 and 1940s, trichinosis was an important food safety factor, but that's gone, essentially, from the food system," Waetke says.

That's because most American pork since the 1990s is raised indoors rather than in pastures. While grass and outdoor pens might sound idyllic, from a food-safety standpoint, pork is much more likely to contain trichinosis when pigs are raised outside, Waetke says. Concrete floors with proper bedding has led to increased "biosecurity," as he puts it, compared to dirt pastures.

"Where that stigma comes from, why people are afraid of that pink, I think it's a very outdated idea. With more advances in how animals are kept and treated and fed especially, that's why we're able to now feel more comfortable eating pork less than really well done," Joe Magnanelli, executive chef of San Diego's Urban Kitchen Group, tells The Takeout. "The pigs that we use, they come from a co-op of farms called Salmon Creek Farms. They're all the same breed, all given the same wheat and barley diet, kept in sanitary conditions, so we can be confident in that."

His restaurants' servers ask guests how they'd prefer their pork chops cooked; if they defer to the kitchen, Manganelli says he'll mostly cook chops to medium or just above.

"I think our clientele are getting more educated on this, too."

Chefs have long been onboard with the less-done end of the pork spectrum. The National Pork Board's announcement of the new pork-temperature guidelines in 2011 includes a quote from one Mr. Guy Fieri, who says: "It's great news that home cooks can now feel confident to enjoy medium-rare pork, like they do with other meats. The foodservice industry has been following this pork cooking standard for nearly 10 years."

One group, however, remains stubbornly behind the times.

"We're doing a lot of education with producers of meat thermometers," Waetke says. "We need to get meat thermometers' [guidelines] changed to that 145."