Old-School Candy Bars That Deserve A Comeback

If you want to thank someone for the candy bar as we know it, thank the fine folks at J. S. Fry & Sons. Candy first started taking on a bar shape for mass public consumption in 1847. Companies like Cadbury and The Hershey Company soon followed suit, launching the next great wave of candy bars. As the 20th century wore on, more and more candy companies, large and small, started producing bars with wondrous flavor combinations and cleverly creative names to boot. While plenty of these "olde tyme" candy bars can still be found at your local store — or on niche corners of the internet — sadly, many have been discontinued and faded into obscurity.

The Takeout hopped into a time machine and traveled across the past two centuries to uncover the old-school candy bars that may have slipped our minds but deserve a history refresher or maybe even a comeback. After all, who wouldn't want a bar that improves on the Reese's Peanut Butter Cup? Or perhaps we can interest you in a slab of chocolate built to withstand 120 degrees Fahrenheit? The stories of these iconic chocolate bars deserve to be retold. Let's hope these bars may one day find their way back into our hands and right into our mouths.

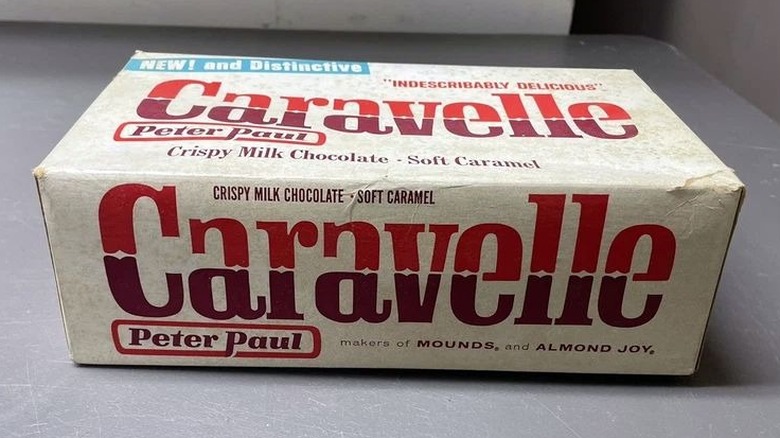

Caravelle

The Peter Paul Candy Manufacturing Company was best known for giving the world Mounds and Almond Joy. In hopes of competing with Nestle's new $100,000 Candy Bar in 1965, Peter Paul conjured up its own milk chocolate bar filled with crisped rice, caramel, and pecan bits. The double bar went by the name Caravelle, eventually ditched the pecan, and quickly proved to be one of the biggest bars for the company since Almond Joy.

Unfortunately, the Caravelle didn't survive Peter Paul's Cadbury-Schweppes acquisition and was discontinued at some point in the late 1970s. Its biggest fans were left heartbroken in its wake. Its loss was so great that it inspired author Steve Almond to write his book "Candyfreak," in which he opined: "How is it that a candy bar, an absolutely sensational candy bar, can be banished to oblivion? How can the lovers of caramel and chocolate and crisped rice be left to satisfy themselves with the mealy indelicacy of the 100 Grand?"

Cherry Humps

Schuler Chocolates of Winona, Minnesota, once sold bars like Time, Duck Lunch, Camel, This and That, Wingold, Sweet Secrets, and Cherry Humps. The latter consisted of a pair of cherries swimming in cordial on creamy fondant, finished with dark chocolate, and was one of Schuler's best sellers.

Over 6 billion Cherry Humps were made during its storied run, which started in 1913. At the apex of its popularity, it ranked as the 16th best-selling candy bar in the entire country. Cherry Humps were such a hit that Schuler tried to launch Mint, Pecan, and Walnut Humps as worthy successors, although they proved not to be as successful.

Even though the candy survived Schuler's sale to Brock's Candy Co. in 1971, a change in the Cherry Humps' manufacturing changed its consistency from soft to firm, helping to fasten its demise. The last batch of Cherry Humps was produced around 1987, with the final bars sold two years later by the Winona Historical Society. Schuler's last bar of Cherry Humps to roll off the production line was once housed at former owner Bill Schuler's home in Winona. While the trademark for Cherry Humps expired in 1995, we would argue that it's ripe for resurrection.

Denver Sandwich

Like a lot of companies at the time, the Sperry Candy Company aimed to convince the public that its products were akin to meals and nutritious to boot. Sperry was a division of the Wisconsin-based Barg and Foster Candy Company, and it was William H. Barg who helped come up with tasty-sounding bars in the 1920s, like the Club Sandwich and the Chicken Dinner. The latter didn't contain any chicken but was such a winner that, decades later, TIME later named it one of "The 13 Most Influential Candy Bars of All Time." Not to be overlooked is another Sperry bar that debuted one year before Chicken Dinner — the Denver Sandwich, which first went on sale in 1922.

While an actual Denver sandwich was served at lunch counters by at least 1902, the candy version was wafer bars layered with milk chocolate and peanuts at its bottom base and encased in more chocolate. The Minneapolis Star-Tribune retrospectively described the Denver Sandwich as "something like a Twix bar, but a little ahead of its time." In 1962, Sperry was acquired by the Pearson Candy Company, and according to the latter, the Chicken Dinner and Denver Sandwich had their last calls by 1968.

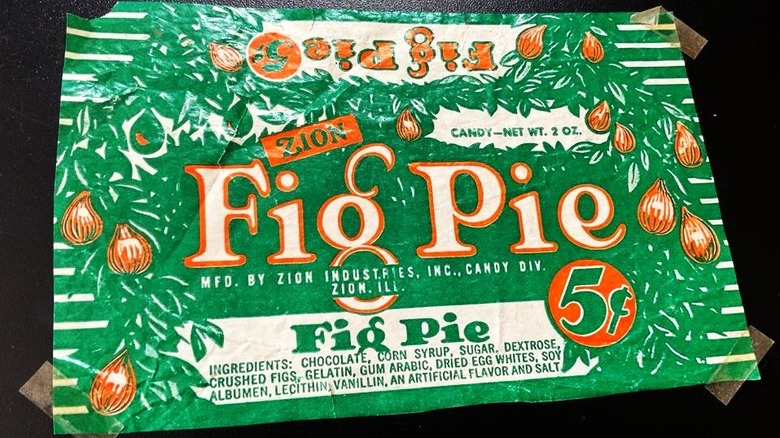

Fig Pie

Fig cookie bars gained popularity when the Kennedy Biscuit Company had the bright idea for a "Newton" product (which aren't actually called Fig Newtons anymore) in 1891. Other companies followed its lead, including one overseen by evangelist John Alexander Dowie and his Illinois-based Zion Industries, Inc. The company's candy division rolled out a line of candy bars in the 1920s, including the Cheer Leader, Cherry Sunday, Cocoaroon, and the Bible-inspired Fig Pie.

Zion wanted sweet-toothed consumers to think of the possibilities with a new kind of candy bar that, in print ads in the Star Tribune, asked them to "imagine fresh figs, creamy marshmallow, [and] milk chocolate." The figs were ground, paired with fluffy marshmallows, and formed into a "pie" with milk chocolate, which once retailed for a nickel. This unique candy bar hung around until at least the end of the 1950s. The Zion Fig Bar was able to outlive the company's demise, but its original marshmallow and chocolate recipe has also become a thing of the past.

Hershey's Tropical Chocolate Bar

The Hershey Company was enlisted by the U.S. Army in 1937 to produce a bar that would not only provide a soldier with nutrients and sustenance but withstand the elements of global battlefield environments, including being wrapped well enough to keep out any poisonous gases. The first such bar, conjured up by company chemist Sam Hinkle, was the Field Ration D, nicknamed the Logan Bar. The 4-ounce bar toned down the sugar content and upped the chocolate liquor content to deliberately taste worse than the regular Hershey's chocolate bar. From 1940 to 1945 alone, it is estimated that 3 billion of these bars were made and in the kits of soldiers around the world.

In 1943, the U.S. Army requested a new kind of bar with an improved flavor and the ability to withstand high heat. The result was Hershey's Tropical Chocolate Bar, which came in 1- and 2-ounce bars and could stay firm against temperatures up to 120 degrees Fahrenheit. By the end of World War II, Hershey's produced 380 million of the 2-ounce bars. In July 1971, a much smaller number of bars even made their way to the moon to nourish the astronauts of Apollo 15. A brief successor to Hershey's Tropical Chocolate Bar, known as Hershey's Desert Bar, came about to aid soldiers in Operations Desert Shield and Desert Storm from 1990 to 1991. Who wouldn't want a civilian version to keep their chocolate from melting today?

Milk Shake

Far from California, a Hollywood with less star wattage in Minnesota lent its name to a confectioner called the Hollywood Candy Company. This produced candy bars such as the Butter Nut, Big Time, Big Pay, Tuesdae, and even one named after the company itself. Hollywood products were once found everywhere — now, they're nowhere. All are worthy of a comeback, but if we could only have one, we would make it Hollywood's Milk Shake.

Hollywood started producing the Milk Shake bar at some point around 1929. It featured malted milk nougat and was billed as tasting just as refreshing as an actual milkshake. It faced likeminded-candy competition when the malted milk balls known as Giants were introduced in 1939, which later became known by its more famous moniker of Whoppers. These are now under the stewardship of The Hershey Company, which also retails two favorites from the Hollywood Candy Company's back catalog: the underrated PayDay bar and the ZERO Candy Bar. The Milk Shake bar became no more sometime after 1990, and it seems unlikely that it will resurface to share shelf space with Whoppers.

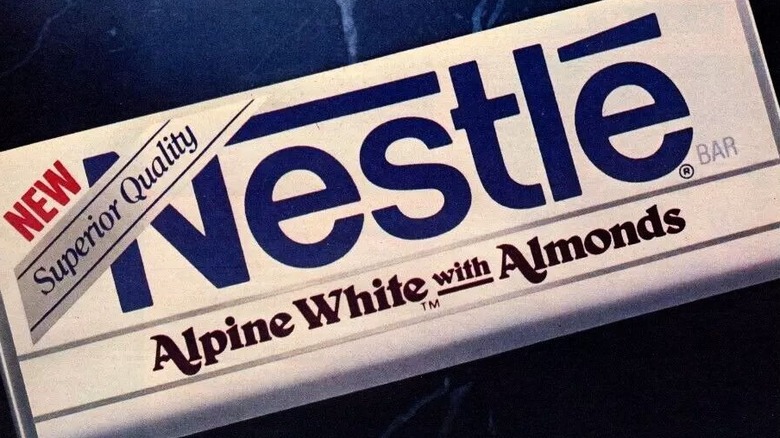

Nestlé Alpine White

White chocolate is a divisive topic among chocolate lovers. Nestlé was one of its earliest pioneers, having released Galak, also known as the Milkybar, in 1936 in Switzerland. Neither made it to the U.S., but finally, in the 1980s, Nestlé introduced a white chocolate product to the nation: Alpine White with Almonds. It wasn't actually the first time that name existed, as a Nestlé Alpine milk product was also released in the 1920s.

Similar in size and packaging to a Nestlé Crunch, this foil-wrapped bar amped up the vanilla flavoring thanks in part to utilizing more cocoa butter than standard chocolate. The new bar was aimed for the adult set. Marie-Claude Stockl, Nestlé's then-director of consumer and public affairs, told The Herald Statesman: "The white chocolate is an upscale idea. It's the kind of thing you associate with white chocolate mousse in fancy restaurants."

Slick ads that aped Maxfield Parrish paintings, paired with a catchy Lloyd Landesman-composed jingle, helped sell it to a new audience. The band Faith No More was so taken by the tune they often covered it in concert. By the tail end of the 1980s, candy like Alpine White helped turn white chocolate into a red-hot food fad. Sometime after 1996, Nestlé ended the sweet dream that was Alpine White with Almonds. While U.S. consumers await a return of a Nestlé white-out, Galak and Milkybar are still making the rounds worldwide.

Nestlé Quik Bar

While the infamous Nestlé chocolate powder product has lived life under several names since the 1930s — such as EverReady and Nestlé Quik – it was the latter's name that inspired the candy bar. The Nestlé Quik Bar, not to be confused with the Nestlé Quik ice cream bar of the mid-1980s, started making the rounds in stores by October 1993.

The Nestlé Quik Bar was produced by Concorde Brands, and the target audience was those who consumed its powder mix — primarily kids aged 2 to 9. The U.S. version of the candy bar was a chewy chocolate bar made with chocolate milk, weighing 1.65 ounces. Meanwhile, the Canadian version was half that size, and a small milk chocolate bar with a white chocolate imprint featuring the brand's mascot, Quicky the bunny. In 1995, a smaller snack-size form was introduced, aptly named Quik Bites.

Customers had to act quickly with this candy, as the bars and bites were later discontinued. The closest one can get to recapturing that '90s magic is the Nestlé Nesquik Wafer Bar, which is sold in Turkey.

PB Max

Reese's Peanut Butter Cups proved to be such a mammoth moneymaker for The Hershey Company that Mars Inc. — then known as M&M/Mars — wanted a piece of that mini-pie. Starting in 1987, the company tested its own take, PB Max, in Peoria, Illinois, and Green Bay, Wisconsin. Three years later, it launched the product nationwide. In lieu of a cup, PB Max was a square affair, where peanut butter and a wholegrain cookie were coated in milk chocolate.

While PB Max had flashy packaging, and hit sales of $50 million, and got its name out there by sponsoring the U.S. bobsled team at the 1992 Winter Olympics in Albertville, France, it seemed doomed from the start. PB Max was apparently axed around 1994. Former Mars marketer director Alfred Poe later revealed in the book "According to The Emperors of Chocolate: Inside The Secret World of Hershey and Mars" why the company gave up on the candy bar. "You want to know why Mars doesn't make any products with peanut butter?" he said. "It's because the [Mars] family doesn't eat peanut butter. They don't like it."

Today, the only two peanut butter-flavored candies in the Mars candy catalog are variants of M&M's and Snickers. For those waiting for PB Max to be the third, you may be better off creating your own with all the copycat recipes floating around the internet.

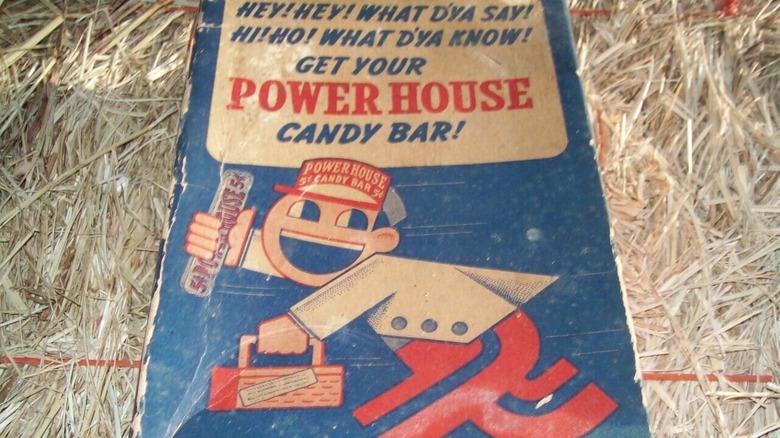

PowerHouse

The Walter H. Johnson Candy Company gave birth to a whopping 4-ounce bar called Power House sometime in the mid-1930s. This hefty candy bar was filled with fudge, caramel, peanuts, and milk chocolate and quickly became a fixture in pop culture. The Power House was featured in the 1940s comic strip "Roger Wilco" and sponsored the 1950s kids' show "The Rootie Kazootie Club." Some chefs even used chopped pieces of Power House to add a perfect finish to their homemade candy apples or a caramel ice cream basket.

After the Peter Paul Candy Manufacturing Company acquired the Walter H. Johnson Candy Company in the 1960s, the new owners kept a light on for PowerHouse (which ditched the space between the two words). It was still being advertised as late as 1987, but a year later, Hershey's acquired Peter Paul from Cadbury's, who pulled the plug on the candy bar. Fans still miss the bar to this day, lamenting the unique flavor of its caramel, which hasn't quite been replicated since.

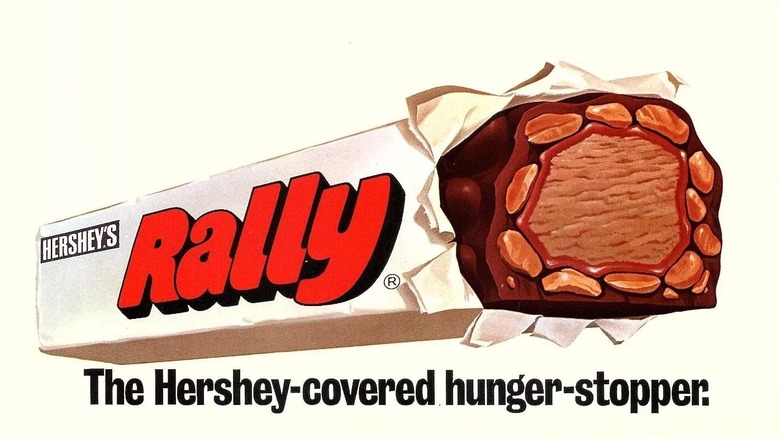

Rally

Just in time for Halloween in 1967, The Hershey Company released a new candy bar called Rally in select locations, including Nebraska and North Carolina. This Snickers-like bar featured peanuts, fudge, and caramel covered in Hershey's signature chocolate. Its availability expanded by 1970, and Hershey's believed in Rally so much that it ran its first-ever outdoor poster and print media campaign in the U.S. to promote this "crowded candy bar" that year (via The Knoxville News-Sentinel).

Rally was packaged in a clean white wrapper, with the candy's logo in a bubbly red font. The "crowded" bar became a little less so in 1975 when it dropped in size from 1.8 ounces to 1.2 ounces within a year due to the rising costs of sugar and chocolate. In 1976, its size grew to 1.5 ounces, and with it came an increase in its price tag.

Eventually, the Rally bar was discontinued in the U.S. around January 1979. However, there's still some hope that we could try it again one day, with Hershey's dusting it off for limited return runs every now and then, as it did in 2008 and 2013.

S'mores

By the 1920s, Girl Scouts were cooking up "Some Mores" over a campfire, sandwiching roasted marshmallows and melted Hershey's chocolate in between graham crackers. In 2003, The Hershey Company finally got around to making a candy bar out of it — S'mores.

Initially, not everyone warmed up to its taste. A review in the Sunday News called out the addition of thickeners, gums, and preservatives and claimed that it was "missing two key ingredients: the campfire and the camaraderie." It also claimed that the bar simply didn't taste like it should and was more like a pale imitation of a 3 Musketeers, noting that "the graham and the marshmallow flavors in this S'mores Candy Bar are extremely weak."

Hershey's S'mores still had its fans and hung around for almost a decade. Eventually, however, the S'mores was discontinued in 2012. Fans have called for its return ever since, and Hershey's even responded to one request by claiming that factors prevented it from relaunching the product but that it wasn't totally beyond the realm of possibility that it would ever return with enough demand.

Summit

Three years after Mars debuted its iconic Twix in 1976, the company introduced its answer to the KitKat in the form of the Summit Cookie Bar. This dual-stick candy was the brainchild of Mars Inc. veteran Thomas Hannon and featured roasted peanut pieces atop a wafer cookie coated with chocolate. It was promoted as light, creamy, crispy, and crunchy, with a young Kathie Lee Gifford seen in TV advertisements quite literally singing its praises.

Summit's packaging and logo were so beautifully designed that it even won an award in 1981. Apparently, none of this was good enough for Mars, which changed everything from the Summit's recipe to its packaging in 1983. Gone were the peanut pieces, and in their place, 30% more chocolate was added to make a longer and slimmer bar encased in a new foil wrapper. In a taste test conducted that year by Star-News, a majority of the panelists couldn't really distinguish the difference between the old and new bars, but one noted, "I prefer New Summit because it seemed a little crisper and fresher."

Despite sales reportedly hitting $40 million, the new Summit bar clearly didn't reach the heights expected from Mars, and it was discontinued. One of the last times it was seen advertised was in the summer of 1985, and even though the bar's trademark name was registered two years later, the trademark was canceled in 2002.

Whiz

The legacy of the Paul F. Beich Candy Company can still be found in the taste of Laffy Taffy, Katydids, and Golden Crumbles. Sadly, there is one key candy missing from that list today: its former bestseller, the Whiz bar.

Whiz came into this world in 1922 as a rounded treat that combined marshmallows, peanuts, and chocolate fudge. The company even deemed the machine that produced 1,400 gallons of marshmallow an hour the "Whizolater." The wrappers ranged from circular silver-foiled ones to a more standard rectangular shape, packaged in a clean white, blue, and red wrapper.

Unfortunately, the good times didn't last forever. In March 1972, the candy bar was discontinued due to a lack of modern production equipment, losing the Paul F. Beich Candy Company $3 million. As The Pantagraph said a year later, the "Whiz — it's out of Biz." There was hope at the time for a revival of the bar, but it appears to never have been fulfilled. Ah, gee-Whiz!