Discontinued Sodas We Don't Miss

Soda — what with all of the highly coveted sugar, caffeine, and tingling bubbles it may promise — leads to deeply entrenched brand loyalties. It's hard to get die-hard fans of one drink to switch over to a brand-new flavor just hitting the market, even if it's an offshoot of a known product or distributed by a major name in soda. It's hard to crack an addiction to even diet soda, but still, soda makers big and small continue to roll out new sodas that almost inevitably flop with the general public, which includes both consumers clamoring for craft soda or something not so mass-produced, and those who can't be swayed by persuasive marketing.

Or, soft drinks get pulled from production and stores, never to be placed back into production because they're gross, odd, or ill-conceived. Sometimes, even a well-intentioned soda manufacturer will confidently unveil a product that just plain tastes bad. There are certainly some discontinued canned foods we miss, while there are plenty of canned drinks we don't. Here are the long-gone sodas that very few people hope ever mount a comeback.

Pepsi A.M.

According to some preliminary market research in the late 1980s, Pepsi pinpointed a specific subset of its customer base: those who drank a can of Pepsi for their morning pick-me-up beverage, rather than coffee. To go after that audience, Pepsi came up with Pepsi A.M. in 1989. Ads for the new soda, which had the same sugar content as original recipe Pepsi and twice as much caffeine, depicted the drink as a cool and contemporary alternative to coffee, represented by older men falling asleep. Pepsi managed to get Pepsi A.M. into the coffee section in some supermarket chains.

But if customers were already drinking Pepsi first thing in the morning and were happy doing that, there was no real need for the manufacturer to produce an entirely different product. Plus, by naming the soda Pepsi A.M., PepsiCo subconsciously and inadvertently told customers when they should use the product — in the morning, and only in the morning. It also didn't help that in taste tests participants reported a poor taste. Pepsi A.M. was discontinued about a year after its debut.

New Coke

Over the course of 99 years, Coke became the bestselling soda in the world, and then The Coca-Cola Company decided to fix what wasn't necessarily broken by changing the recipe. Startled by Pepsi's aggressive takeover of market share since 1970 and its consistent victories in taste tests, The Coca-Cola Company built a better Coke, which 200,000 people said was an improvement. Not only was it much sweeter than original Coke, but the revamped one was made with fewer oils and less natural flavorings, which stood to save the company $50 million annually.

New Coke hit the scene in April 1985, with the original formula disappearing. The public loudly and vehemently rejected the retooled soft drink. Coca-Cola fielded as many as 1,500 complaint calls a day and endured in-person organized protests. About 100,000 people joined groups like the Society for the Preservation of the Real Thing and Old Cola Drinkers of America with the sole purpose of getting Coke to reinstate its tried and true product. Less than three months later, Coca-Cola admitted fault and resumed production on old Coke, which from that point would be called Coca-Cola Classic. To appease consumers who actually liked New Coke, the company kept it in production under the name Coke II. That drink, which really just tasted like a Pepsi clone, sold in small numbers until it was discontinued in 2002.

OK Soda

In the 1990s, Coca-Cola's marketing department learned that the two best-known words across all languages were supposedly "Coke" and "OK." Seeking to own the trademark on both, The Coca-Cola Company created OK Soda. But how do you get people interested in a product that proclaimed its casual mediocrity? By embracing a jaded and disaffected sensibility, reflecting the attitude associated at the time with members of Generation X, the teens and 20-somethings of the 1990s who seemingly felt "OK" about most things.

It took Coca-Cola two years to come up with the marketing plan for OK Soda, because it would be tough to attract customers who were young and distrusted advertising and corporations. Ads for the soft drink went self-deprecating, featuring a listless "OK Manifesto" (per "OK: The Improbable Story of America's Greatest Word"), which included aphorisms like "What's the point of OK? Well, what's the point of anything?" An attempt was made to make OK Soda cans seem cool and relatable to youthful consumers, with Coca-Cola hiring indie comic book artists Daniel Clowes and Charles Burns to design them.

OK Soda sold very well in limited test markets, but didn't when it was accessible nationwide. Coca-Cola's research showed that customers who bought OK Soda once tended to not buy it again. For while much work went into the marketing, the soft drink itself was just OK, a bland and nondescript fruity-flavored soda and cola hybrid. After about a year, Coca-Cola took OK Soda out of stores.

No-Cal

When Brooklyn soda proprietor Hyman Kirsch went to work for the Jewish Sanitarium for Chronic Disease in New York, he got the idea to concoct a drink that the center's patients with diabetes and heart issues could enjoy — something without all the sugar and unnecessary calories found in every other soft drink in the mid-20th century. Kirsch and his son created No-Cal in 1952, the first diet soda in history. Countering the bestselling colas and lemon-lime soft drinks available everywhere, No-Cal sold a line of four extra-sweet flavors: ginger ale, root beer, black cherry, and chocolate.

The product sold moderately well throughout the 1950s and 1960s, but there was a limited market in the era for diet sodas, as No-Cal was pitched solely to diabetics and people who needed or wanted to eat less sugar and consume fewer calories. Even if consumers liked the taste, it was always beside the point. By the early 1970s, No-Cal slowly faded from public view. Inspired by the potential demonstrated by No-Cal, the bigger brands came out with their own diet drinks and in the popular cola flavor, including Coca-Cola's Tab and Pepsi's Patio, later renamed Diet Pepsi. Furthermore, the non-caloric sugar substitute used in No-Cal, cyclamates, were banned from use in the U.S. in 1970 after studies suggested the substances could be carcinogenic.

Coca-Cola Blak

The explosive spread and popularity of Starbucks and other purveyors of high-end, coffees and coffee-based beverages in the 2000s made Coca-Cola's corporate office very nervous. Losing market share and money as countless consumers switched from its caffeinated, sugary products to those made by Starbucks, Coca-Cola bit back in April 2006 with Coca-Cola Blak.

Described as a fusion beverage, it combined original Coca-Cola with coffee flavoring. Sold in 8-ounce plastic bottles colored a coffee brown, at a much higher per unit and per ounce price than other Coke-made beverages at the time, Coca-Cola Blak tasted like coffee-flavored hard candies, or a heavily sweetened cup of coffee gone cold, or a cup of coffee mixed with Coke.

The flavors didn't exactly merge, but this was the end result of Coca-Cola's in-house scientists spending two years on a coffee-based soft drink. "It's not for everyone," Coca-Cola marketing executive Katie Bayne said to the Atlanta-Journal Constitution early in the product's life. "It is an adult cola taste." In August 2007, Coca-Cola announced that it wouldn't make it anymore in the U.S., but would continue to do so tentatively in France, Canada, and other smaller markets.

C2 and Coca-Cola Life

For most of history, sodas either had a lot of sugar, or they had very little or none. As both types serve a specific sector of consumers, it doesn't seem like there's a need for a product in the middle, a soda that has some sugar, but not too much. And yet in 2004, Coca-Cola came up with C2. First released during an upswing in the popularity of low-carbohydrate diets — whose adherents would be more inclined to drink normal diet soda — a glass of C2 contained about half as many calories and sugar as a Coke. However, C2 did claim to contain "all the great taste" of original-recipe Coke in its ad campaign. It did taste a lot like Coke, albeit cut with a Coke alternative made with a sugar substitute (which is pretty much exactly what C2 was). Less than a year after it unveiled C2, Coca-Cola stopped making the product, which it blamed in part for the company's substantial 3% drop in annual sales volume.

Nevertheless, The Coca-Cola Company attempted the regular-diet mix again in the U.S. in 2014. This time, Coca-Cola Life was presented as a natural product, sold in packages with green labels and made with real cane sugar (not heavily-processed high fructose corn syrup) and plant-derived Stevia extract (instead of aspartame). This gambit lasted until 2017, its death the result of poor sales.

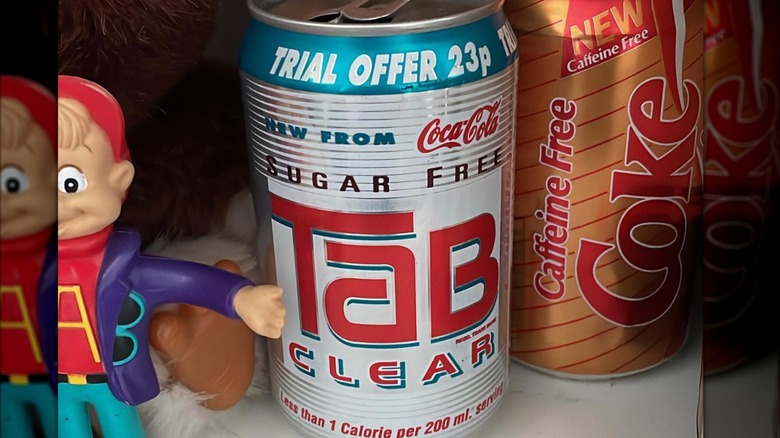

Tab Clear

As part of the clear beverage craze of the early 1990s, Pepsi released Crystal Pepsi, and Coca-Cola answered with Tab Clear. Pepsi spent 18 months developing the recipe for Crystal Pepsi; Coca-Cola needed only two, because its product was conceived with failure in mind. By that time, Tab was passé, introduced in the mid-1960s and down to a market share of under 1%. Coca-Cola executives figured if they positioned Tab Clear in the market, figuratively and literally, against Crystal Pepsi, consumers would think of the strange, outdated old soft drink and assume that Pepsi's new product was also a diet brand. If Tab Clear was a successful product, that would be fine with Coca-Cola; if it failed, however, it wouldn't bring shame to the company name, only to the already dying Tab.

While Pepsi spent $40 million promoting Crystal Pepsi, Coca-Cola soft-launched Tab Clear in 10 cities in early 1993 with plans to go national by the end of the year. It's unclear if Coca-Cola's plan had anything to do with it, but Crystal Pepsi flopped, as did Tab Clear. Pepsi's transparent drink captured a 0.5% market share, with Tab Clear selling even worse. Both drinks were out of stores in 1994, although Crystal Pepsi has occasionally been revived for limited runs — but not Tab Clear.

Josta

An extra-caffeinated, supplement-enhanced version of soda, energy drinks have become a phenomenon in the 21st century. While energy drinks might extend our lives they're maybe also probably messing with our hearts, meaning it's going to take a while to form a broad cultural opinion on the subject. Nobody knew much about energy drinks at all in 1996, when Pepsi pioneered the segment with a jacked-up soda called Josta.

The flavor profile was greatly different than anything else on the market at the time, tasting like a spiced, heavily sweetened cola with elements of cherry, chocolate, fruit juice, cough syrup, and whatever was imparted by South American guarana berries, the active ingredient that provided a bigger dose of caffeine than a normal soda or a cup of coffee. Josta took off only with young people, not enough for Pepsi to justify continued production, and the company stopped making it in March 1999.

Pepsi Blue

Less than a decade after the cola-flavored but curiously not cola-colored Crystal Pepsi failed to seduce consumers of established sodas, PepsiCo once more tried to sell the world on a soft drink with an odd new taste and a wildly different hue. In the summer of 2002, Coca-Cola began production on a vanilla-flavored version of its flagship product; Pepsi responded with Pepsi Blue. Reportedly winning out over more than 100 other ideas it developed, Pepsi Blue scored high marks with teenage taste-testers, who promised that they'd buy the product on a consistent basis if it were offered.

Pepsi positioned the blue drink as a "berry cola fusion," meeting the intersection between fruit-flavored sodas and traditional colas. It tasted far more like the former than the latter, however, with notes of bubble gum present in the mix. About a year after Pepsi Blue launched, it was clear that the product had failed, with Pepsi executives telling the media that while teens and younger adults had purchased it, it sold abysmally in other demographics. Research suggested that Americans preferred their colas (and cola-adjacent beverages) to stay brown and retain the cola flavor. In a head to head battle with Vanilla Coke, the competition won in year one, moving 90 million cases versus Pepsi Blue's 17 million. In year two, Pepsi Blue sales fell to 5 million cases. The company quietly — because the soda had so few fans — discontinued Pepsi Blue in the spring of 2004.

Orbitz

Hitting stores in 1988, Clearly Canadian offered a novel product: sweetened, fruit-flavored sparkling water. In 1996, Clearly Canadian created a new line of products even more curious called Orbitz. Marketing materials touted Orbitz as a drink of the future, or a "texturally enhanced alternative beverage," according to Fast Company. Likened to a lava lamp, Orbitz was sold in glass bottles which allowed for viewing of the multicolored gelatinous, edible, and chewy "orbs" that floated through the liquid.

Unlike Clearly Canadian, Orbitz wasn't carbonated, but it leaned on its predecessor's propensity for bold fruit flavors, although Orbitz's were so imaginative as to be confusing, including Raspberry Citrus, Blueberry Melon Strawberry, and Cherry Coconut. Reviewers at the time compared the taste of various Orbitz styles to household cleaner, cough medicine, and stale water. That's to say nothing of the orbs, gelatin-like with a density the same as the surrounding liquid, generally considered strange and unappetizing, the result of food science gone amok. Orbitz sold well in an aggressively marketed test run, clearing the way for its availability across the U.S. by the end of 1996. By that time, most people who'd wanted to try Orbitz had, and they didn't like it. Sales fell precipitously, and Clearly Canadian stopped making the drink in 1999. In the 21st century, hardcore fans missing Orbitz have asked the manufacturer for a revival. That's not possible — the company had gotten rid of all the specialized gear necessary to make such an odd beverage.

Aspen

Fruit-flavored options represent a big part of the soda market, particularly citrus varieties like lemon-lime and orange, while berry and grape sodas have their fans. But one of the most common items in the produce aisle has never made an impact in soda outside of smaller and craft bottlers, and that's the apple. Not counting the perennial popularity of Martinelli's Sparkling Cider as a non-alcoholic alternative to champagne, no major soda company presently makes an apple flavor. In 1978, Pepsi gave it a shot with Aspen Soda.

PepsiCo targeted an emerging, untapped audience as the group to whom it would market Aspen: young, wealthy adults interested in luxurious and premium products and experiences colloquially referred to as "yuppies" (extrapolated from "young urban professionals"). A representative ad depicted a couple dressed in white and riding white horses through a snowy glen. The commercial touts Aspen Soda as "crisp and crystal clear" that provides "a tantalizing snap of apple" that will whisk the drinker away to "a sparkling world of refreshment." Aspen Soda ceased to exist in 1982 after four years of poor sales, although Pepsi reformulated and rebranded the soda into a new flavor in its Slice line. That apple soda didn't take off either.

Vio

Pepsi advises putting a little milk in your Pepsi to make a trendy dirty soda or approximate the taste of a float. That's more palatable than rival Coca-Cola's fruit-flavored and carbonated sodas built on a foundation of milk. Such drinks are commonly consumed in Asia, but not in the United States, which is where Coke launched this line of bubbly and fizzy milks in 2009 with flavors like Citrus Burst, Peach Mango, Tropical Colada, and Very Berry. Packaged in 8-ounce bottles, a single serving of Vio was initially priced at $2.50, or more than double what a traditional soda in a container more than twice as large may cost.

Perhaps to downplay the milk element, a big leap from consumers used to sweetened and flavored carbonated water, Coca-Cola marketed Vio with the meaningless marketing designation of "vibrancy drink," according to Smithsonian Magazine. It couldn't pitch it as a healthy choice, because even a small bottle contained 26 grams of sugar. Ultimately, Vio got some curious attention from the media when it was unleashed in test markets, from which it never emerged.