Cheerwine: The Southern Drink That Was Invented For A Not-So-Sweet Reason

Any southerner worth their salt knows (or at least thinks they know) all about Cheerwine. Most will tell you it's a cherry-based soft drink made in North Carolina. A further astute few know that the "wine" in the name comes from the color, not because it ever had psychoactive substances (unlike Coca Cola which did indeed have cocaine, or the lesser known connection between 7UP and lithium). But the origins of Cheerwine are quite a bit less cheery than its fruity effervescence might otherwise imply.

Necessity is often the mother of invention, and that was certainly the case of Cheerwine's invention during the sugar shortages of the First World War. Disrupted supply chains, the embroilment of beet-producing nations in Western Europe, and soaring demand for sugar as a preservative in military rations all made refined sugar a scarce commodity. As a result of wartime shortages, the U.S. Food Administration promoted food conservation through alternate diets (this is where "Meatless Mondays" come from) and ingredient substitutions.

Perceiving a gap in the market, Cheerwine founder LD Peeler of Salisbury, North Carolina sought to break into the soft drink business despite the sugar shortage which had driven so much of his competition out of business. He found his competitive edge among the wares of a St. Louis-based flavor salesman, who presented an almond-oil based syrup that tasted like cherry in 1917. This concoction was super sweet without a massive input of raw sugar.

Cheerwine proved a hit throughout the Piedmont region of North and South Carolina, and has endured as a regional staple for over a century since. Peeler's family maintains control of the company today, with their flagship drink enduring both the Great Depression and a virtual monopoly by Coca Cola.

How wartime has shaped modern pantries

Cheerwine wasn't the only food (and drink) -stuff born of wartime necessity. It's a common bit of trivia that Fanta was created in Nazi Germany, but once again it's a story rooted in scarcity. The German division of Coca Cola was unable to import their patent syrup from the United States, spurring the creation of a new product made exclusively of commonly available food byproducts including apple fibers, whey, and cider mash.

On the other side of the Atlantic, the U.S. military was also cooking up wartime rations in novel ways. Ohio-based immigrant and Italian chef Hector Boiardi had been canning his restaurant's famous ravioli as a take-out item since 1937. However, the US military approached him to ramp up production of "Chef Boyardee" ravioli as a shelf-stable ration for American troops overseas.

M&Ms are yet another example of rations that transcended their military purpose to become a household staple. M&Ms were invented specifically for American MREs (Meals Ready to Eat) as tasty, energy-rich supplements that didn't melt in the pocket due to their hard candy coating. The sheer scale of M&Ms production carried over after the war into the domestic market.

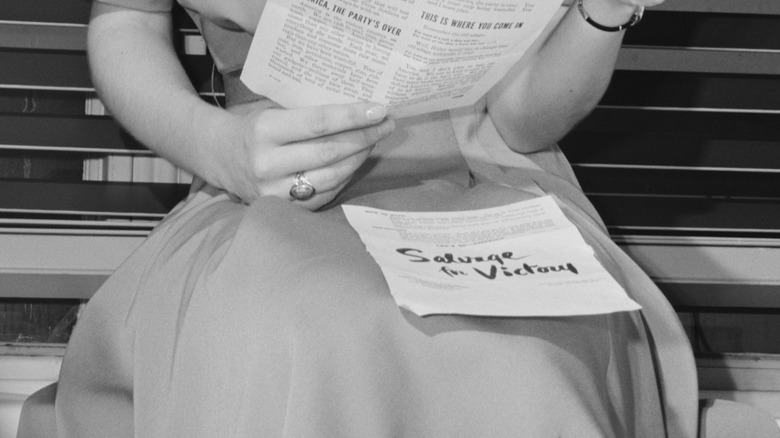

Economies of scale weren't the only thing propelling wartime foods into the domestic culinary zeitgeist. Procter & Gamble, for example, published entire cookbooks promoting its product Crisco as a patriotic alternative to lard and butter during WWI. Similarly, marketing companies were quick to seize upon the opportunity to develop military surplus powdered cheese products as shelf-stable staples befitting the modern, convenience-focused households of the postwar era. Thus were born quintessentially American processed foods like Kraft macaroni and cheese, Fritos, and Cheez Whiz.