Once-Popular Beers That Sadly Disappeared

Beer drinkers have a lot of choices. The average supermarket or convenience store stocks shelf after shelf of the stuff, not even including the mass-market ciders and seltzers, and all of it's fairly similar to one another. Big time brewers differentiate their products through interesting marketing or making a product that's consistently tasty, refreshing, or singular. The beers that meet those criteria become bestsellers and tend to enjoy loyalty from customers who count on those brews day in and day out, year after year.

Today's American beer industry is the result of industry maneuvering and innovation that began in the 1800s. As you can't store an opened beer in the fridge for long, beer brands don't last forever either. Countless varieties have come and gone, from hops-infused ales to subtle lagers to bold and heavy craft beers. Through it all, collective tastes change, and businesses are bought and sold or fall apart completely. This results in even acclaimed, widely liked, and important beers ending production. Some beers that were enjoyed for generations and which reached iconic status simply aren't made anymore. Along with the discontinued canned foods we miss the most are the canceled frothy alcoholic beverages, the famous beers of yesteryear that disappeared.

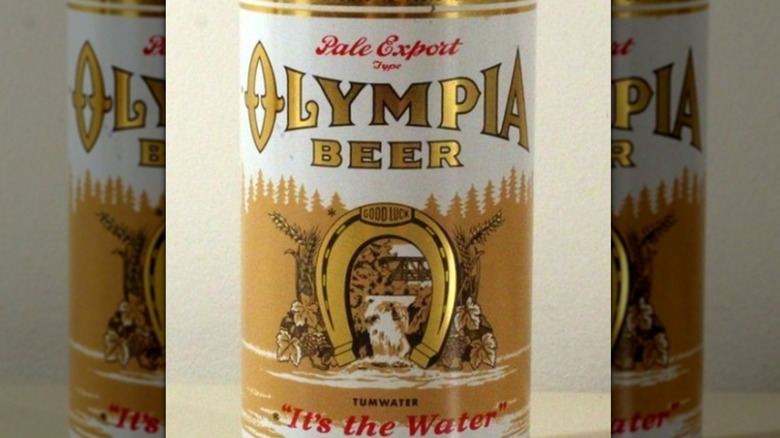

Olympia

Until the late 20th century, the overwhelmingly preferred style of beer in the U.S. was the German-style lager. Light on taste, color, and alcohol content, lagers go down easily and were provided by many major regional breweries across the country. In the Pacific Northwest, the local mass-produced lager of choice was Olympia Beer, brewed since 1896 at a facility in Tumwater, Washington, not far from the state capital of Olympia. Its signature selling point was that it was made from carefully treated, locally-sourced spring water, a fact referenced to the marketing slogan that appeared on every can of Olympia Beer: "It's the water."

In 2003, the much larger Pabst Brewing Company bought the Olympia Brewing Company and shifted production to a factory in California. Olympia's lager continued to occupy store shelves on the West Coast for the next 18 years, sold to a consistently shrinking customer base. Citing that "growing decline in its demand" on the Olympia Beer Instagram account, Pabst stopped brewing the popular lager entirely in early 2021.

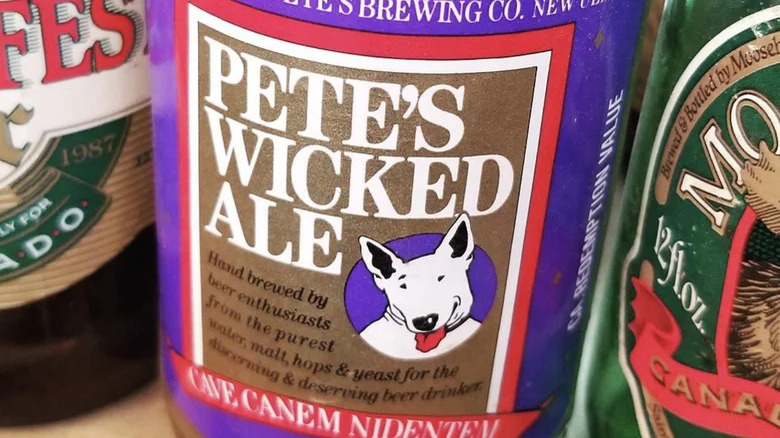

Pete's Wicked Ale

Into the American beer scene of the 1980s, dominated by watery, gently-flavored mass-produced lagers like Budweiser and Miller, came Pete's Wicked Ale. In 1979, Connecticut home winemaker Pete Slosberg moved over to beer because it took less time to make; by 1986, he'd established a company to bottle and sell Pete's Wicked Ale, a pioneering American Brown Ale that was dark, thick, flavorful, and had a high alcohol content. With its quirky profile and small batch production method, Pete's Wicked Ale was among the first ever microbrews, or craft beers.

Slosberg created a few more beers to add to the line, but none proved as popular or as influential as Pete's Wicked Ale. In 1998, he sold his whole operation to The Gambrinus Company, which changed the recipe in 2000 to make the Wicked Ale taste not so heavy. Changing an original beer's unique flavor proved to be a bad move, and in 2011, with sales cratering, The Gambrinus Company announced that it would cease production on Pete's Wicked Ale.

Brown Derby

Safeway, the most popular grocery store in many states, helped popularize the concept of beer sold in cans. Utilizing a process perfected in the 1930s, Safeway brought in northern California beer-maker Humboldt Malt and Brewing Company in 1935 to produce a store brand beer available exclusively at the supermarket's outlets, primarily located in Western states. That low-cost, pilsner-style light ale was called Brown Derby, and Humboldt was forced by a lawsuit to change its original can's design featuring a derby hat and umbrella because it looked too similar to the marketing imagery of Los Angeles's Brown Derby restaurant. Regardless of the packaging, Safeway customers bought so much Brown Derby pilsner that Humboldt very quickly found itself struggling to produce enough beer. By 1938, Safeway had to call upon multiple small breweries to help make its private label beer, which would also include a lager.

While Humboldt shut down in 1940, various other breweries kept brewing Brown Derby ale for Safeway for decades. The rising popularity of national brands in the mid-20th century cut into the market share of local and regional breweries, and Safeway could no longer compete. It stopped ordering Brown Derby pilsner from its suppliers in 1988, and it disappeared from Safeway store shelves when the stock ran out.

Meister Brau Lite

"Light" beers — those with a large portion of naturally-occurring calories scientifically removed in the brewing process and among the best-selling beers in the U.S. in the 2020s — have only been around since the 1960s. Rheingold Brewing biochemist Dr. Joseph L. Owades perfected a way to extract the starchy carbohydrates from beer without it much affecting the beverage's alcohol content or flavor. It was such a radically new product that Rheingold had to market it not as a competitor with other beers but as a diet product and a weight loss aid, hitting stores in 1967 as Gablinger's Diet Beer. That product failed so quickly and thoroughly that Rheingold let Dr. Owades try out the underlying concept later that year with a rival brewery, Meister Brau. The Chicago-based beer company marketed the same beverage, previously known as Gablinger's Diet Beer, as Meister Brau Lite, and as part of a line of calorie-reduced health foods.

After Meister Brau went out of business entirely in the early 1970s, some of its most popular products were swiped up by other companies, namely Meister Brau Lite. In 1972, the Miller Brewing Company adapted the recipe slightly and re-launched the low-calorie beer as Miller Lite.

Bud Dry

Yeast is a living organism, and it consumes the sugars found in starches like wheat or rice and converts those to alcohol. That's how beer is made; the slightly sweet aftertaste found in many mass-market brews comes from the sugars the yeast didn't finish eating. In the production of dry beer, emerging as a popular style of beer in Japan in the 1980s, extra yeast is used in the process of brewing to ensure that virtually all of the starches are eaten and turned into alcohol, which better eliminates any sweetness or aftertaste. In 1989 and 1990, Anheuser-Busch brought dry beer stateside in a big way by slapping the best-selling, well-known, and trusted Budweiser name on a product it called Bud Dry.

Marketed via an aggressive ad campaign that lasted well into the early 1990s, commercials for the product cryptically touted the new beer's smoothness and posed rhetorical questions answered with the tagline, "Why ask Why? Try Bud Dry." Probably out of a collective curiosity for a new Budweiser product whetted by those persuasive ads, Bud Dry sold briskly until the mid-1990s, before consumers moved on. Anheuser-Busch slowed down production in 2006 and stopped making Bud Dry altogether in 2010.

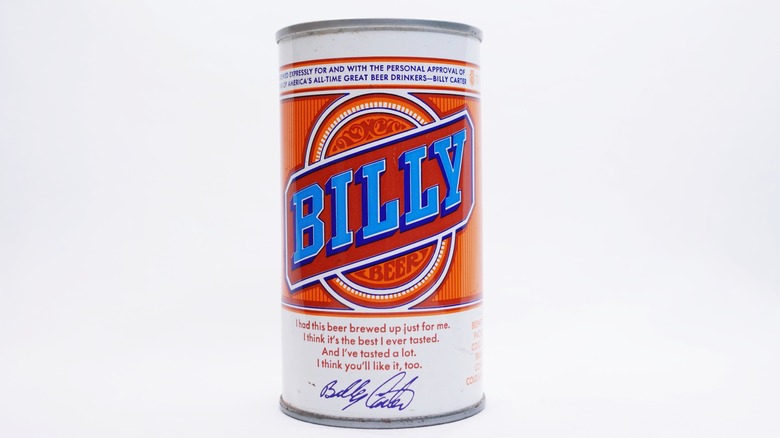

Billy Beer

Southern culture enjoyed a big moment in the late 1970s. "Smokey and the Bandit" was a smash hit movie, "The Dukes of Hazzard" was a TV ratings success, and Billy Beer was briefly one of the most talked-about beers in the United States. While peanut farmer and Georgia governor Jimmy Carter won the presidential election of 1976, his brother got a lot of media attention. Billy Carter, perceived as a friendly, down-to-earth guy, ran a gas station, and often told reporters and discussed in speeches his love of guzzling beer.

Falls City Brewery, operating out of Louisville, Kentucky since the early 1900s but on the verge of ruin by the late 1970s, attempted to save itself in 1977 by launching a line of beer named after and endorsed by the new president's brother. Billy Carter earned $50,000 for his naming rights and some appearances in commercials for Billy Beer. Cans of the standard lager also bore a cheeky quote attributed to Carter: "I had this beer brewed up just for me. I think it's the best I ever tasted. And I've tasted a lot." Plenty of six-packs of the fad beer, which tasted a lot like so many other readily available beers, were sold throughout 1977, but not enough to give it a significant market share or to save Falls City. The brewery went out of business in 1978, thus permanently ending production on Billy Beer.

Red White & Blue

The Pabst Brewing Company released an appropriately patriotically named beer just in time for Independence Day 1899 — Red White & Blue. Eminently drinkable because of its light flavor and texture and very low alcohol content of 3.2% ABV, Red White & Blue was inexpensive to produce and thus marketed as a budget brand in the Midwest. By the 1970s, consumers in the Milwaukee area could score a six pack of the crispy lager for under $1. It became such a local favorite for cost-conscious Milwaukeeans that popular bar The Avalanche used Red White & Blue to power its "naked beer slide" promotion throughout the 1980s.

In the 1990s and later, consumer interest in Red White & Blue faded, and Pabst responded to the market by producing less and less of the beer until it was bottling almost nothing. Then it became a legacy brand revived for special events only. Around the Fourth of July in 2018, Pabst celebrated Red White and Blue, featuring the brew in a beer garden at its official taproom in Milwaukee and adding it to the facility's taps. That was the only place in the world where Red White & Blue could be found. Now it's unavailable everywhere, because the taproom closed in 2020.

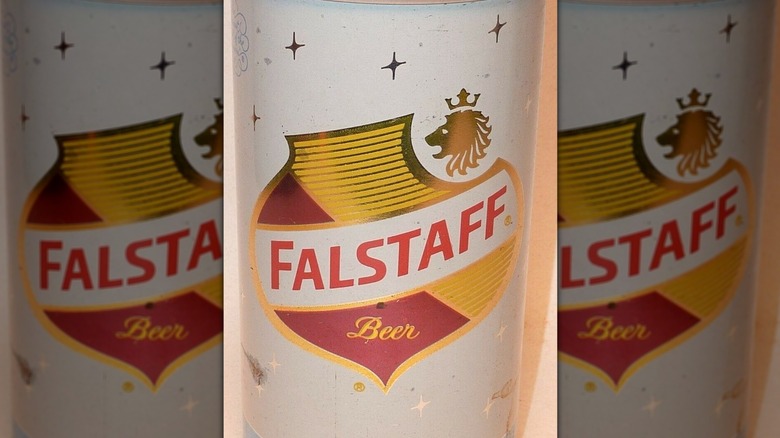

Falstaff Lager

After the federal law prohibiting the sale of alcohol was repealed in 1933, U.S. residents developed a big thirst for beer, particularly lightweight, American-style, German-inspired pale lager. Two of the biggest distributors of that beer at the time both operated in large part out of St. Louis — Anheuser-Busch (with its Budweiser) and Western Brewery, recently sold and renamed the Falstaff Brewing Company, in honor of the recurring, booze-loving Shakespeare character.

Over the next few decades, Falstaff elevated itself from a regional brand into a national one, buying out smaller, struggling breweries in St. Louis and other cities to better produce and distribute its signature lager. The gambit worked — by 1960, Falstaff was the third-biggest American beer company, trailing Anheuser-Busch and Schlitz. But then it faded due to the increasing popularity and utter domination of Budweiser. By 1975, Falstaff had fallen to eleventh-place in the beer world, and Pabst parent company S&P bought out the corporation. By 1990, only a single plant in Fort Wayne, Indiana, still made Falstaff beer, before S&P discontinued it entirely in 2005.

Krueger's Cream Ale

In January 1935, the Gottfried Krueger Brewing Company took a gamble on an emerging technology and showed the world that beer wasn't just for kegs, bars, or bottles anymore. After years of trying, the American Can Company finalized the pressurized metal beer can in 1933, and signed on the Newark, New Jersey-based Krueger to be the first brewer to distribute its product in single-serving thin aluminum containers. It was a futuristic move for an old, historical brewery, opened by German-American uncle-nephew duo John Laible and Gottfried Krueger in 1858. Kruger's Finest Beer and Krueger's Cream Ale first hit stores in Virginia as a test, and the novelty of canned beer, namely Krueger's Finest Beer and Krueger's Cream Ale, helped the previously modestly sized Krueger compete with the bigger companies, and by 1952 the brewery was churning out a million barrels' worth of beer every year.

In the 1950s, industry dominant brewers like Miller and Anheuser-Busch ramped up production and absorbed or eliminated a number of smaller, regional brewers. The Gottfried Krueger Brewing Company was a victim of this major economic shift, and by 1961, when it was acquired by northeastern U.S. competitor Narragansett, it had stopped production entirely, even on its historically important canned Krueger's Finest Beer and Krueger's Cream Ale.

Henry Weinhard's Private Reserve

Henry Weinhard opened the first major brewery in Portland in 1856, a mere five years after the city was incorporated. Eighty years and many styles later, and after the operation expanded into a regional beer giant known as Blitz-Weinhard, the brewery released what would become its flagship product, and one named after its founder: Henry Weinhard's Private Reserve. It gained popularity for its taste — it was a smooth and drinkable, malt-forward Bavarian-style lager — Private Reserve was also inexpensive and was one-of-a-kind in the marketplace in that it was made with a newly available and locally developed flavoring agent, Cascade hops.

Falling somewhere between light-tasting macro-brews and the hops-heavy craft beers that would follow in its wake, Henry Weinhard's Private Reserve remained a bestseller throughout the Northwest throughout the latter quarter of the 20th century. But in 1999, Blitz-Weinhard shut down its Portland brewing plant, and the company was acquired by Molson Coors, which moved production of Private Reserve to other facilities. In 2021, the parent company announced that it would no longer make many legacy beers, such as Henry Weinhard's Private Reserve, choosing to focus its resources on hotter properties like craft beers and alcoholic seltzers.

Hair of the Dog Adam

Portland is home to one of the country's most robust beer scenes, with more than 80 small breweries operating in and around the city that helped spawn the global popularity of craft beers. Homebrewer and Portlander Alan Sprints started Hair of the Dog Brewing Company in 1993, launching with what would endure for decades as one of his best-selling offerings: Adam, a contemporary reimagining of a style made for centuries in Dortmunder, Germany. Deep brown in color with a very high alcohol by volume level of 10%, Adam was a thick, powerfully flavored, notably bitter and very bubbly ale that Hair of the Dog recommended consuming as a dessert and paired with chocolate and cigars.

When Sprints decided to retire in 2022, Hair of the Dog soon thereafter ended production on all of its beers, including Adam, but still offering what remained to the public. "I did have quite a few cases of bottles and many barrels of beer aging at that time and have been selling it since then. I have bottles that are available on my website and I am selling kegs of the barrel aged beers as well," Sprints told The Takeout. But unless someone steps in, that's probably the last of Adam. "I had hoped to find a brewery to take over my spot but I am still looking," Sprints explained.

Kirkland Signature Light Beer

Costco's chain of warehouse-style membership stores sells a lot of alcohol, including products under its house label, Kirkland Signature. The company contracts with specialty businesses to make those items, including Kirkland Signature Light Beer, a 4.2% alcohol by volume pale lager — the same scientific, nutritional, and flavor profiles as that of Bud Light, the reduced-calorie market leader it was clearly designed to compete with.

Your favorite beer might just be from a brewery giant, and that was the case with Kirkland Signature Light Beer. Made by the likes of the Gordon Biersch Brewing Company, the New Yorker Brewing Company, and the Minhas Craft Brewery, among others, over the years, Costco sold scores of Kirkland Signature Light Beer in part because it could be purchased only in bulk, and at bargain level prices. By the 2010s, a box of 48 Kirkland Signature Light 12-ounce beers cost just $22 at the average Costco warehouse. The product lasted just a few years, with Costco quietly discontinued the brand in 2018.