Shady Things About Colonel Sanders

We may receive a commission on purchases made from links.

You've probably been told to avoid meeting your heroes, unless you want them to disappoint you. Unfortunately, the same cane be said about meeting your favorite mascot. Although most mascots aren't actually based on a real human, and you could never truly meet them, this was not the case with Colonel Sanders of Kentucky Fried Chicken fame. The man behind the famous fried chicken franchise was, in fact, a real person, and there was a whole lot about him that was nothing short of shady.

Born on September 9, 1890, Harland Sanders' life as the founder of America's most popular chicken shop might seem touched with good fortune. However, there was a dark side to it: indecision, infidelity, lies, brawling, anger, and obsession make for an interesting story to share, and not without real harm.

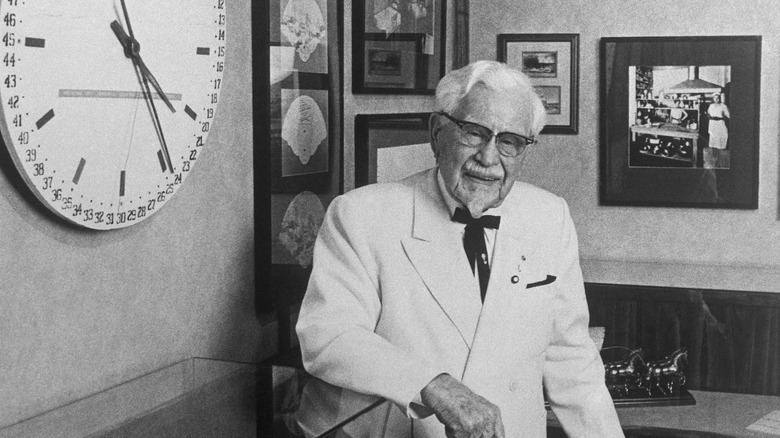

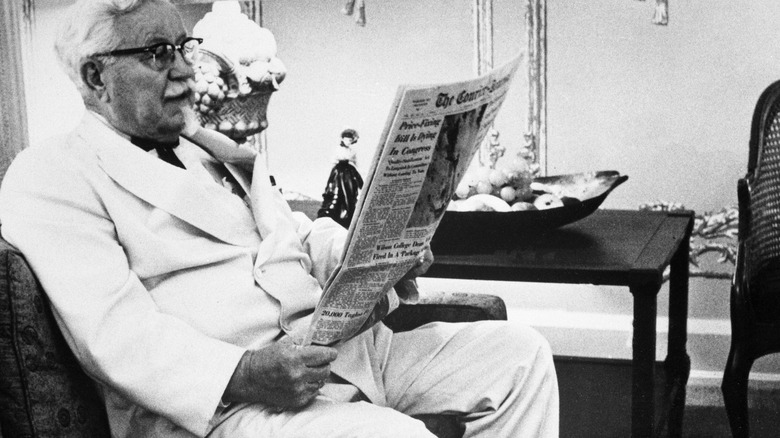

From the decisions he made, the way he treated the people he should have loved the most, and the choices he made in business, the details about Colonel Sanders reveal he is much more than a man in a white suit. Though we can't interview the legend today, a swath of biographical information helps us understand that even though his face is lit up at thousands of KFC across the world, the true details of Colonel Sanders' life are pretty shady.

He dropped out of school

For a man who eventually did so well in business, it may be striking to learn that this suit-clad icon didn't have a complete education. Dropping out in and of itself isn't shady, but the decision to abandon school rather than build a life in which he could balance the importance of education suggests that Harland Sanders was willing to give up when certain things got hard. It's a decision making process that's easy to track across the rest of his life.

Granted, some of Sanders' decision to leave school was out of his control. The eventual mascot of Kentucky Fried Chicken grew up poor. The family met a fair amount of tragedy in Sanders' younger years. First, his father died when Sanders was five. The family struggled to get by; Sanders' mother remarried a man who Sanders would never see eye-to-eye with. This marriage led to Harland and his younger brother to individually leave home.

To make it, Sanders needed to leave school to work full-time. However, it seems the need to make money wasn't the only reason Sanders left. He explained that the math subject algebra was introduced into his seventh year curriculum, but the he couldn't really figure it out, nor did he have the desire to struggle through it. All told, the Colonel claimed that he "lost out in a wrestling match with algebra." As a result, he dropped out rather than balancing working on a farm and going to school to finish out his education.

The Colonel lied about his age to enlist

After abandoning his education when it got too hard, he took a few different jobs before landing in New Albany, Indiana. There, he worked as a streetcar conductor since he was quite a strong and large looking young man who appeared older than his actual age would have you believe. It wasn't the last time Sanders smudged his age. At one point, he was mistaken for being old enough to join the army, rather than being the younger teenager he was. Sanders ran with it.

As Sanders tells it in "The Autobiography of the Original Celebrity Chef," he met a man while working as a streetcar operator who asked him if he would enlist and go to Cuba. The promise of good pay was convincing. Although Sanders wasn't old enough to join, he did, even if not yet 16 years old.

In his autobiography, Sanders seems wholly coy about wether his age was ever asked, but does admit that if it was, he lied. In Cuba, he worked in the quartermaster's corps, but, since the conflict cooled out in less than a year, he was only in the army for a few months. Though he never served as a colonel, Kentucky Governor Ruby Laffoon bestowed this honorary title in 1935, almost 30 years after he enlisted in the army.

He's known to be a job jumper

When changing jobs frequently, sometimes Sanders would quit, but other times, he was fired, revealing a serious issue with long term commitment. Returning from Cuba, he began as a blacksmith's helper as part of the Southern Railroad in Sheffield, Alabama. After a couple of months, he went to Jasper, Alabama, to clean locomotive pans and then was a fireman on the Northern Alabama railroad. Ultimately, he would lose that position.

Next came a string of employments at Norfolk and Western Railway, then Illinois Central Railroad, followed by Rock Island Railroad, before going to Little Rock to study law and eventually practicing with the Justice of the Peace courts. Ultimately, he left law to go back to the railway work with the Pennsylvania Railroad. Growing weary with cleaning privies, he began working with Prudential Life Insurance Company selling insurance before eventually running a ferry boat company followed by the office of Secretary of the Chamber of Commerce in Columbus, Indiana.

In a steep turn from ferryboats and chamber of commerce, Sanders manufactured and sold farm lights. Unfortunately, for Sanders' pocketbook, this didn't pan out, and he ended up losing the business. From there, Sanders worked with a series of other companies and jobs: Michelin Tire Company, Standard Oil, and delivering babies (yes, really) before returning to food. For someone who has been on the KFC bucket since 1952, Sanders demonstrated a lack of obligation when it came to holding down a job.

He ended his legal career after a brawl

For the few years Sanders spent studying and practicing law, he showed a lot of promise ... until he didn't. In "The Autobiography of the Original Celebrity Chef," Sanders simply writes: "I decided I didn't want to be a lawyer anymore." Of course, like any juicy story, there was more to it than suddenly up and ending a whole legal career. Sanders outed himself on this fact in his second autobiography, "Life as I Have Known it has Been Finger Lickin' Good."

Though he left school with only a sixth grade education, Sanders was able to practice in the Justice of the Peace Court. At the time, it did not require that lawyers pass the bar. Though the cases were relatively minor, Sanders found himself in quite the pickle with a client, D. Scott.

Scott was in trouble for missing payments to a loan shark. The case was taken to trial, and though the details are murky, Sanders and his client lost. However, that wasn't the worst of it. D. Scott's wages were being garnished by the loan shark, and the amount included Sanders' fee.

Rather than lose out, Sanders went behind the backs of client and the J.P. He set a lien on Scott's paycheck with his employer. The whole mess of business resulted in Scott becoming so angry at Sanders that he clobbered the Colonel. In response, Sanders then picked up a chair like it was a tables-ladders-and-chairs match in the WWE. Before he could strike, several sheriff deputies stopped him. It wasn't the last time Sanders' anger drove his actions.

He attempted to defend turf in a shootout

In his later autobiography, 1974's "Life As I Have Known It Has Been Finger Lickin' Good," Sanders mentions but doesn't really address the incident in which he got caught up in a turf war and shot at his own competition. But it's a shady thing that happened to Sanders.

As Sanders tells it, "One man was killed, and in self-defense, I shot a man who killed the other fellow." He calls this a "shootin' scrape" and explains that since relatives of the affected were still alive, he preferred not to talk too much about it.

The full story feels very in line with the winding tale of Colonel Sanders' life. While running his gas station on Highway 25, Sanders had a large sign painted to direct customers to his station. His competitor, Matt Stewart, was not a fan of the sign, since Stewart also had a station just down the road. Of course, the two were competitors. Rather than just leaving Sanders be, Stewart repeatedly painted over it, which would prompt Sanders to paint over Stewart's job, and threaten to shoot him.

Eventually, Sanders and two Shell employees were able to catch Stewart in the act. The resulting gunfight took place over the sign; one Shell employees was killed, and Stewart took some shots, too. In the end, Stewart was charged with murder while the remaining Shell employee and Sanders got off free. The gas station became the first of Sanders' restaurants.

Colonel Sanders once conspired to abscond his own children

Colonel Sanders may have had more careers than you would have ever imagined, but he also was pretty shady in the relationship world. In fact, his wife, Josephine, grew so frustrated with his job hopping from position to position, she opted to live with her family for a period of time.

In "Life As I Have Known It," Sanders' brother-in-law wrote to Sanders, saying, "Josie's at home with her folks where she ought to be. She had no business marrying a no-good fellow like you who can't hold a job." This apparently was quite difficult news for Sanders, and when he discovered that even his furniture had been distributed amongst the neighbors, he devised a plan to kidnap his children.

His plan was to hang out in the woods, waiting for the children to come out and play outside of the King family home. Then, he planned to head out of town via train, kids in tow. This didn't happen because the children never came out. Sanders seemed to think better of his plan, approached the home, and made amends of some kind. The two would come back together, but the marriage wouldn't last. In the end, Josephine and Harland divorced after they had raised their children. The Colonel went on to marry Claudia Price, his former mistress.

Sanders struggled to keep his hands to himself

Though it's hard to say exactly why someone decides to look outside of a marriage for intimate connections, with Sanders, the excuse seemed to be that his first wife, Josephine, showed no interest in a physical relationship with him after the birth of their three children. As a result, Sanders' justified himself by seeking out other women, notably one who would later become his second wife, Claudia Price.

Harland Sanders' daughter, Margaret Sanders, defended the Colonel in her own biography by saying "Neither promiscuous nor a whoremonger, Father nevertheless had a libido which required a healthy, willing partner. He found one in young Claudia." However, what "The Colonel's Secret: 11 Herbs & A Spicy Daughter" doesn't say is that Price wasn't the only woman Sanders pursued.

Slate reports that in 1999, a biographer of Sanders' named John Ed Pierce recounted how he was once told by a woman that she would practically have to beat Sanders' hands off of her in order to be left alone. Similarly, a journalist for the New York Times reported in 1970 that Sanders had a penchant for admiring and commenting on women that surrounded him. This was certainly one persistent, problematic Colonel.

He was known to freak out when food disappointed him

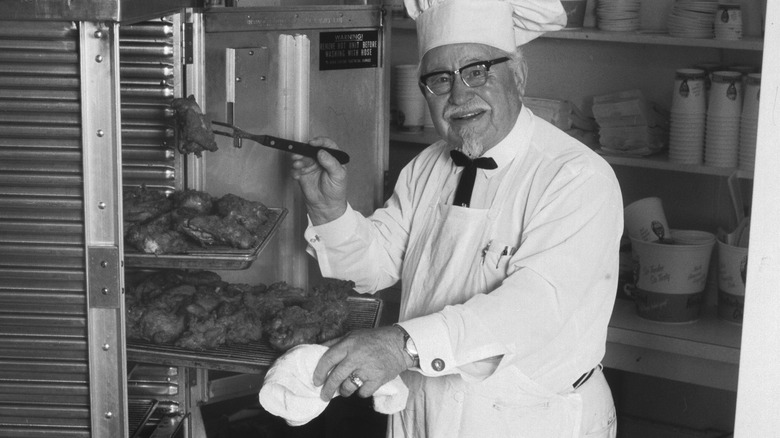

Even after Colonel Sanders sold KFC in 1964, he remained on the board of directors. Within the organization, he was well respected for his culinary knowledge and would make stops at different stores throughout the country to assess the quality of the product. KFC executives seemed to appreciate the Colonel for what he did, but rumor goes that they were also quite terrified of him because poor food quality would set him off like nothing else.

Colonel Sanders' obsession with the quality of the fried chicken and KFC menu quality didn't start late in his career; it had always been there. Sanders admits in his first autobiography that he'd probably been thrown out of more restaurants than anyone else, because he insisted on telling owners that their chicken could be cooked better. And he knew how to do it. This determination certainly transferred over to the way he dealt with franchisees. Even before he sold, he had a steadfast determination to expect perfection in regard to the quality of his product — and was quick to anger if standards did not meet his expectations.

The Colonel was mad shady about the gravy

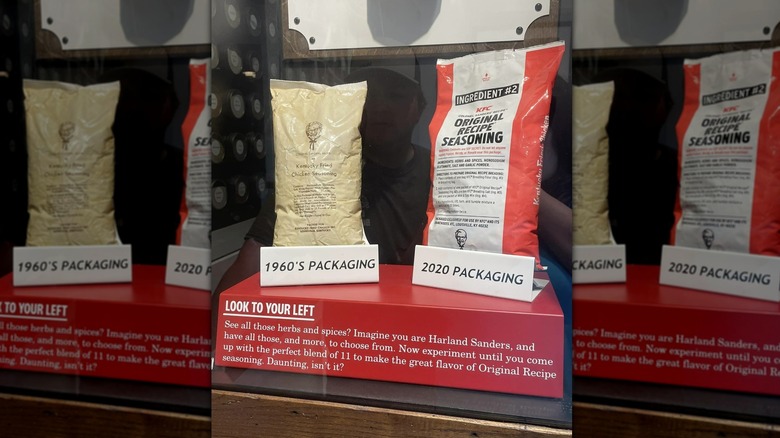

Colonel Sanders was proud of his chicken, but his gravy was on a whole other level. It's recounted in "The Autobiography Of The Original Celebrity Chef" that Sanders once told a new franchisee that if "you make gravy good enough you can throw away the chicken and just eat the gravy."

This gravy was part of the magic that sold the very first Kentucky Fried Chicken franchises and part of the reason KFC would become a chain of restaurants. The Colonel had a very specific idea for how the KFC gravy should be prepared. In fact, he claimed that most of the gravy he encountered, he would never even feed to his dogs. He wasn't interested in good, and his intensity about perfection and the way he treated those attempting to reach it is another reason we deem the Colonel "shady."

Sanders wanted an absolute commitment to being perfect, even if it meant losing money. Unable to do anything tangible about the gravy issue, Sanders would visit restaurants and offer intense critiques, calling it "slop" and banging his cane about. With time, Sanders sold the business. The gravy needed to change because it was apparently quite difficult to replicate accurately, especially with the level Sanders expected. Not to mention, it was expensive.

He went after KFC's parent company with a lawsuit

In January 1974, Colonel Sanders sued Heublein, the parent company of Kentucky Fried Chicken, for over $122 million. The charges addressed in the suit were twofold. For one, Sanders alleged that his image was being used inappropriately to sell non-Kentucky Fried Chicken products, like pastries and bread. Sanders, always the one wanting to be in control, alleged concerned that using his image to represent these products would make it look like he had control over their quality. Given how angry he could become over gravy made wrong, this frustration isn't surprising. And it wasn't the only reason. Sanders also alleged that he wasn't getting residual income from the uses.

The other claim Sanders offered in the suit was the allegation that the company was doing everything it could to keep the Sanders family from franchising a new restaurant, Claudia Sanders, The Colonel's Lady Dinner House. Though this was a sit-down restaurant, it's not hard to imagine why Heublein would have feelings about Sanders' new restaurant. Though the suit would eventually settle, it was for a relatively meager amount compared to his initial claim: just $1 million. This couldn't be the last time the two parties met in court. After Sanders went on record calling the restaurant's gravy sludge, the company pulled an Uno reverse card and sued Sanders over libel and defamation for what he said in the interview.

His outfit didn't change ... for 25 years

Some might argue that wearing the same clothing day after day allows you to focus on more important things. It cuts down on the required decision making, but it also institutes something of an identifiable uniform. Think Steve Jobs and his iconic turtleneck, for example.

Colonel Sanders turned himself into a caricature by wearing the very same thing for the last 20 years of his life. He actually had different weighted coats in the summer versus the winter to help ensure consistency. In the winter, he wore wool but in the summer, he enjoyed a lighter cotton suit. This way, he would never be seen without that iconic Colonel look in public.

Even still, the Colonel wasn't always the icon of KFC. In the beginning, Kentucky Fried Chicken was spelled out with little chicks coming out of their shells. Then, 1952 introduced the face of the Colonel to the logo, which has remained, more or less, part of the company's iconography since then. After never appearing in public in the last 20 years of his life without the suit and tie, in death, he continued the look, being buried in that iconic white suit with a string type bow tie. The Colonel may have died, but the brand brought back the image with Darrell Hammond taking on the role for ads. A few months later, Norm Macdonald would replace him with Jim Gaffigan taking up the image in a Super Bowl commercial.

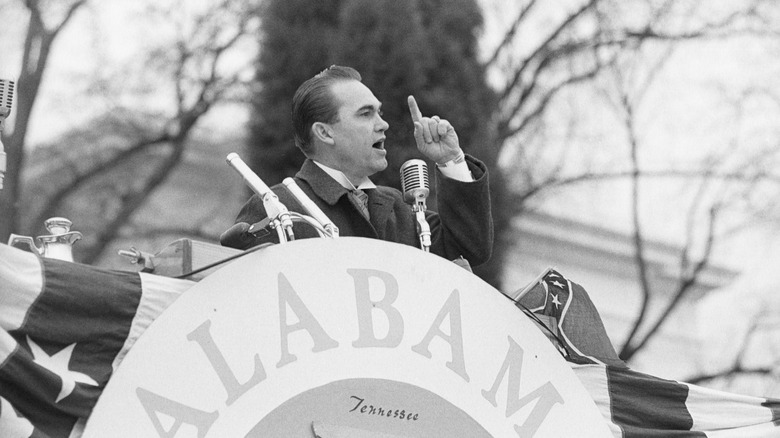

The Colonel was connected to racist governor George Wallace

The name George Wallace may not immediately ring any bells, but if you don't recognize the name, part of his gubernatorial inaugural speech may sound familiar. In January 1963, at the height of the civil rights movement, he was the politician who ended his speech with "segregation now ... segregation tomorrow ... segregation forever." This, of course, gives you solid insight into the perspective of how Wallace operated and his feelings on equal rights.

What you might be surprised to learn is that Colonel Sanders had ties to Wallace. In Wallace's 1968 run at the presidential election, he considered Colonel Sanders as a potential running mate. While he was considered a potential running mate, Sanders was also a contributor to Wallace's campaign. In the end, Wallace chose Curtis LeMay.

Wallace wasn't the only politician Sanders was connected to. In fact, he did work for Happy Chandler during his gubernatorial campaign. Sanders was always soured about how Chandler seemed to forget who elected him, leaving Sanders in the dust after the election. It wouldn't be too far of a stretch to say that he would become bitter about this, and we might even go so far as to infer that this could have been part of the reason Sanders backed Wallace, even as Chandler attempted to gain the same vice president spot Wallace was in talks for.