We Need To Stop Thanking Thomas Jefferson For Mac And Cheese

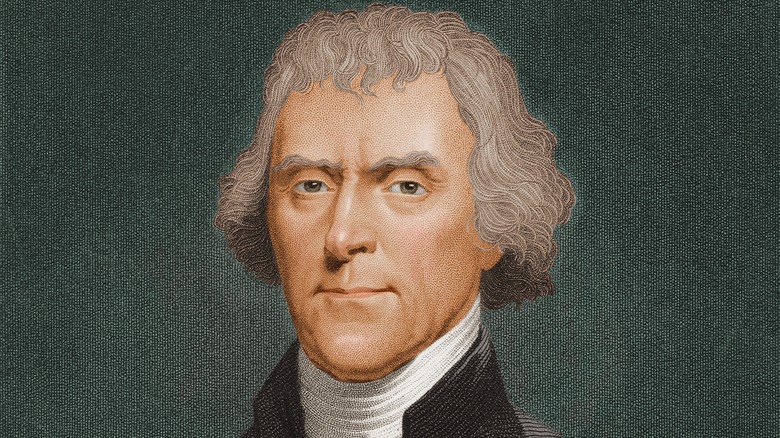

Thomas Jefferson was undoubtedly a busy fellow — in addition to penning the Declaration of Independence, serving as our third president, and founding the University of Virginia, he also found time to invent or improve a number of gadgets. He is also one of America's Founding Foodies and, as such, helped to establish the American wine industry in his vineyards at Monticello. One thing he's sometimes credited with, however, is either inventing macaroni and cheese or introducing it to this country.

The former idea is patently untrue, as pasta with cheese has been around since ancient Rome (if not longer). As for the latter — well, Jefferson may have helped to popularize the dish, as any recipe gets some shine when it's associated with somebody famous. Even so, the fact that at some point he wrote out a (cheese-free) macaroni recipe, which has been preserved in the collection at Monticello, doesn't mean he was in the kitchen cooking the stuff.

No, the actual macaroni-making was no doubt done by one of his enslaved kitchen staff, possibly James Hemings, who, despite being considered Jefferson's property, was also a relative of sorts. While Jefferson probably didn't consider him to be a family member, James was the brother of Sally Hemings, who had six children with the former president. James also trained as a chef during the 1780s while Jefferson was serving as the ambassador to France and brought back recipes for pommes frites (aka french fries), meringues, and ice cream in addition to macaroni.

A brief history of macaroni and cheese

Some historians consider the first macaroni and cheese to be a Roman dish called placenta, consisting of layers of cheese between dough. Modern reconstructions of the recipe, however, make it seem more like the Greek cheese pie called tiropita. In 13th-century Italy, a few more cheesy pasta recipes surfaced, one called lasanis and the other lasagne. (No marinara sauce in these proto-lasagnas, though, as tomatoes weren't introduced to Europe until the 16th century.) Within the next few centuries, Italians would be producing pasta dishes that sounded somewhat similar to modern-day cacio e pepe, but once the dish made it across the border to France, it became considerably creamier.

By the 18th century, creamy, cheesy noodle puddings were well-known in France and England, and in 1769, we see the first recipe for a dish that's not too dissimilar from the macaroni and cheese we know today. It was printed in a book called "The Experienced English Housekeeper" by Elizabeth Raffald, and quite a few copies were sold in Colonial America as well as in England.

It seems likely that James Hemings learned to prepare macaroni while living in France, and he may well have cooked it for Thomas Jefferson once they returned to the U.S., but he was no longer living by the time "macaroni pie" was being dished up in the White House. The first published American recipe was, instead, credited to Sarah Rutledge, who authored the 1847 cookbook "Carolina Housewife."

Jefferson was interested in the technical side of macaroni-making

While Thomas Jefferson probably didn't hand-craft his own pasta, much less cook it up in a cheesy sauce, he was sufficiently hands-on as to get involved with designing a pasta machine to his specifications. He'd always been a tinkerer, it seems, turning Monticello into the 18th-century version of a smart home, complete with dumbwaiters to move items between floors and a revolving book stand that would allow him to have multiple books open at the same time. When he traveled to Europe and encountered pasta, so intrigued was he that he made extensive notes and drawings for a machine meant to produce the stuff, and these papers now reside in the Library of Congress.

Not only did Jefferson study the pasta maker, but he obtained one from Naples in the early 1790s. It's not known, however, whether he (or James Hemings or anyone else) put it to much use. Records dated between 1809 and 1816, after Hemings' death, show that Jefferson's household purchased a fair amount of ready-made pasta. Some of it was produced in Trenton, New Jersey (site of the nation's first pasta factory), while the rest was imported from Italy.