What's Bologna? ¯\_(ツ)_/¯

Bologna gets a bad rap. Critics call it mystery meat, saying it's full of leftover meat bits that you'd never want to know about. But I do. I want to know bologna's secrets.

Here's why: If 49 percent of Americans eat a sandwich on any given day, and assuming some not-insignificant percentage of those are bologna sandwiches, millions of Americans are consuming bologna right this very instant. (As the 1973 Oscar Mayer jingle so persistently earwormed into our brain, Americans "love to eat it every day.") In 2016, Americans spent half a billion dollars on the stuff. Surely we should give this popular luncheon meat the investigation it deserves.

So here's what bologna is.

By United States Department Of Agriculture definition (called a "standard of identity"), bologna is a cooked and/or smoked sausage, grouped in with hot dogs, frankfurters, wieners, and the like. This standard of identity specifies bologna be a semisolid product made from one or more kinds of "raw skeletal muscle" from livestock like cattle or pigs.

Uh, what's raw skeletal meat?

"Skeletal muscles are those muscles attached to the skeleton," a USDA Food Safety And Inspection Service spokesperson tells The Takeout, and those muscles may come from cattle, swine, sheep, or goat. Bologna may, by definition, also contain poultry meat and spices.

Another important distinction: Bologna, like other cooked sausages, must be comminuted, or reduced to tiny particles. In sausage-making terms, that's done using a bowl chopper or emulsion mill that turns meat into "batter." That semisolid is pressed into casings to form bologna or hot dogs; later, that casing is removed.

This smooth, emulsified texture is primarily what makes American bologna different from Italian mortadella, which has visible cubes of pork fat and is seasoned with pistachios or red pepper. Unlike American bologna, the National Hot Dog And Sausage Council notes, Italian bologna needn't be cooked; it can be a dry or semi-dry sausage. The smoothness of American bologna has become its calling card—as none other than chef David Chang puts it, bologna is "a blank canvas of pureed meat."

Sure, pureed meat, but what else? That USDA definition continues: Bologna may contain no more than 40 percent combined fat and water, and no more than 3.5 percent non-meat extenders such as cereal grains or milk. If a bologna is labeled "with byproducts" or "with variety meats," it may contain no less than 15 percent of one or more kinds of raw skeletal muscle meat with raw meat byproducts. And those byproducts—organ meats, typically—must be spelled out plainly on the label. So what makes up that other 85 percent? A USDA Food Safety And Inspection Service spokesperson says it can consist of "safe and suitable ingredients" like "salt, corn syrup, garlic, and sugar." (According to Janet Riley of the National Hot Dog And Sausage Council, you're not likely to find "variety meats" bologna on many grocery shelves anyway. She says she's tried.)

As with all foods, labeled ingredients must be listed in order of predominance, starting with the most prevalent ingredient. In Oscar Mayer sliced bologna, that's actually chicken, followed by pork and corn syrup; Oscar Mayer's sliced beef bologna is primarily beef, water, and corn syrup. Bar-S Meats classic bologna lists chicken, pork, and water as its top ingredients, while in Hormel deli-style bologna, the first ingredients are pork, water, and beef.

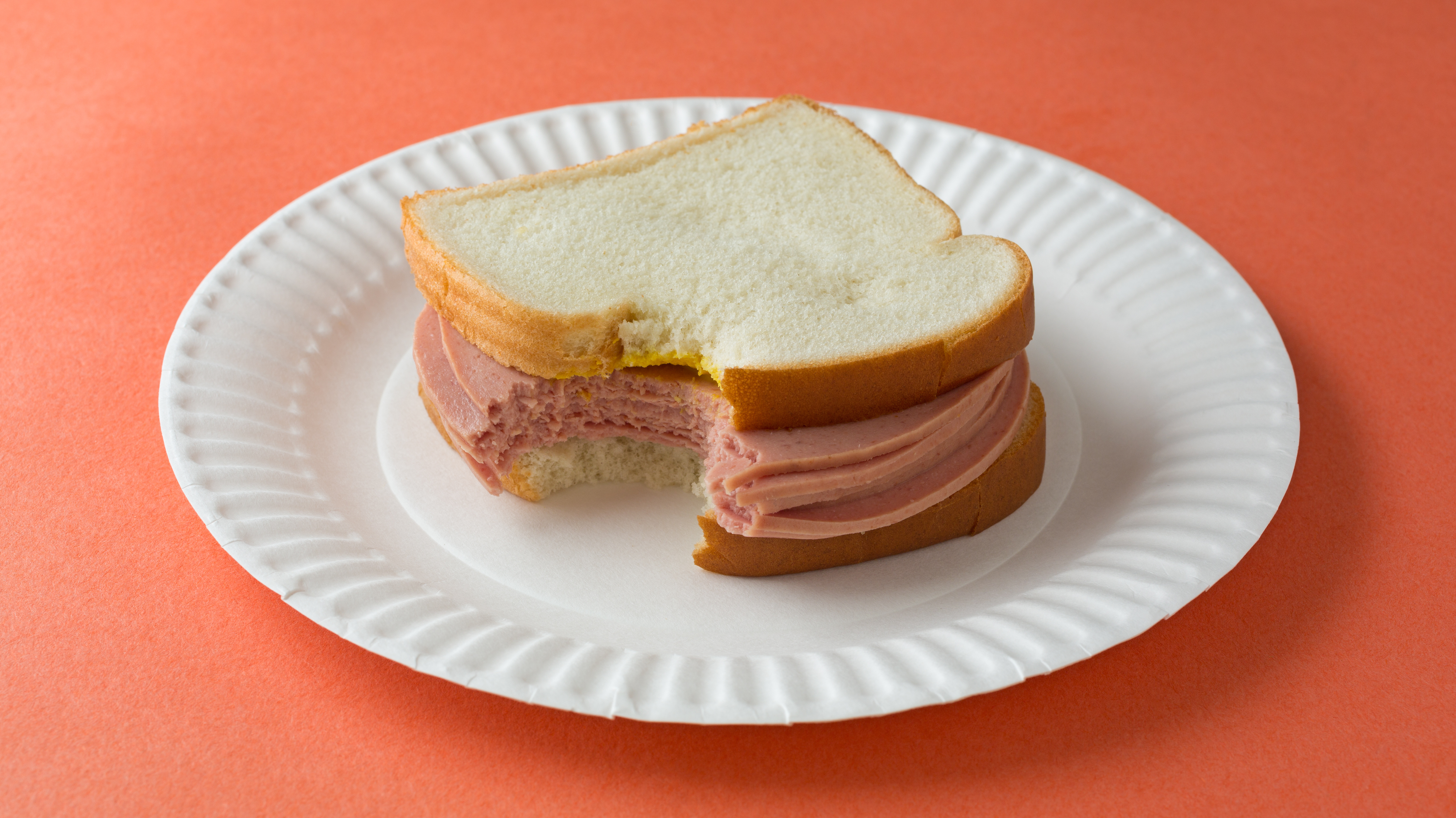

Chefs have lately been spiffing up bologna, as David Chang's piece mentions, serving venison-and-pork versions or semi-ironic fried bologna sandwiches with artisanal mustard. Your supermarket's standard-variety, pre-sliced stuff though? It's still likely to be made of pureed chicken, pork, or beef, probably with some corn syrup.

After all this, I found it's not terribly difficult to find out what's in the packaged bologna you're holding—just flip it over to read its ingredients as you could with any other food. Mystery solved.